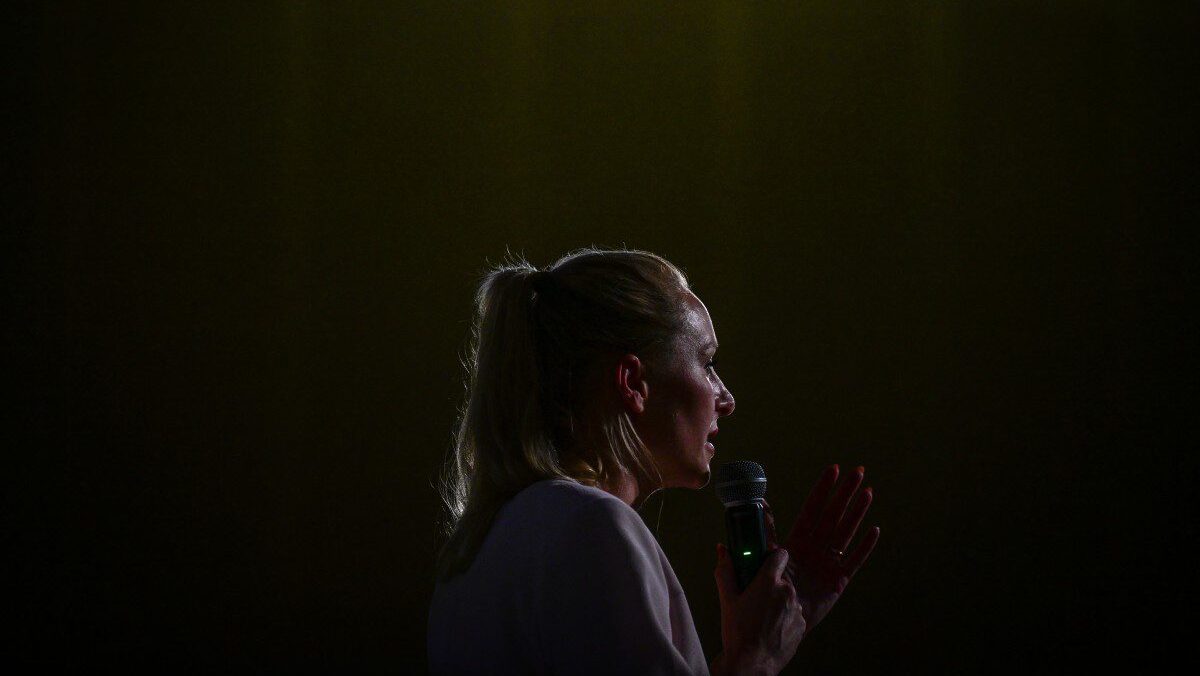

Marion Maréchal, the niece of Marine Le Pen, began her political career as part of the Front National (FN) in 2012. Five years later, she stepped away from politics after the rebranding of FN into Rassemblement National. She later returned to public life by launching the Institut des Sciences Sociales, Économiques et Politiques (ISSEP) in 2018 and joining Éric Zemmour’s party, Reconquête, in 2021. Maréchal held the position of executive vice president within Reconquête and was the head of the party’s list for the 2024 European elections. However, she left Reconquête in mid-2024 due to strategic disagreements over electoral alliances during the legislative elections. A few months later, Maréchal announced the creation of her new political party Identité-Libertés (IDL) in October 2024, which aims to unite the French Right for good and fill what she describes as a “vacant space” on the French political spectrum.

Identité Libertés embodies the ethos of the civilizational Right. This Right affirms a vision of identity centered on a people defined by Greco-Latin culture and Christian faith. Our commitment to preserving this unique way of being in the world—expressed through our national cultures, traditions, views on family and gender relations, aesthetics, attitudes toward mortality, and countless other nuances—drives our opposition to mass immigration and the Islamization of society. The civilizational Right also stands resolutely against the woke agenda, exploitative taxation, and excessive dependence on welfare systems. We aim to dismantle the ingrained socialist mentality (socialisme mental) that pervades public life in a variety of different ways and defend both public and individual liberties with unwavering determination.

This was a coincidence—but perhaps also a sign? The victory at Lepanto safeguarded European civilization through the unity of several states under the banner of the Holy League. This triumph was largely due to the technical and tactical genius of the Europeans, particularly their deployment of six heavily armed galleasses that decimated the numerically superior Ottoman fleet. Coalition-building in the face of a common adversary and confidence in the ingenuity of our civilization—this is, in essence, what Identité Libertés is all about.

Following the dissolution of the National Assembly, I sought to reopen dialogue with the Rassemblement National (RN). Throughout the European elections campaign, I made it unequivocally clear that the RN was a competitor, not an adversary. However, Éric Zemmour persisted in his strategy of overt hostility toward Marine Le Pen, who ultimately deemed his rhetoric too divisive for any alliance between the RN and Reconquête. So, I was faced with a choice: either I support Reconquête’s nationwide candidacies—ignoring political realities and jeopardizing the national camp’s necessary victory, even at the risk of empowering the far-Left—or back the historic union between the RN and Éric Ciotti, then president of Les Républicains, who had courageously crossed the Rubicon. I chose the latter, and consequently, Zemmour expelled me from Reconquête, along with the party’s two other vice-presidents, Guillaume Peltier and Nicolas Bay. I would also like to point out that the electorate has by and large supported our approach. While my European election list garnered 1.4 million votes, Reconquête’s legislative candidates secured a mere 238,000.

This coalition must be as broad as possible, but this must be done while respecting each of the components of such an alliance. Debout la France has its place in it. Reconquête, as I have just explained, is currently trapped in a strategy of radical opposition. This saddens me—especially for all those campaigners, dedicated members, and activists I have grown to know and for whom I hold great respect. Nonetheless, I have no doubt that they will make the right choice as the long-awaited victory of the national camp, to which we all aspire, finally comes into view.

While our trajectories differ, we do complement one another. On matters of identity and immigration, I have always spoken candidly, and reality proves me right more and more every day. My civilizational perspective has also grown increasingly pronounced: during the European campaign, I was the only candidate to initiate debates on surrogacy and euthanasia. More recently, I voiced the discomfort and shock of many French people over the Summer Olympic opening ceremony in Paris, denouncing the scandalous desecration of the Last Supper, the crowing depiction of Marie-Antoinette’s decapitation, and the glorification of polyamory. France has so much more to offer the world.

No, on the contrary, the Rassemblement National has actually been instrumental in this coalition, agreeing during the last legislative elections to support Éric Ciotti’s candidates, as well as those I put forward. These candidates are now affiliated with the RN group in the National Assembly and have joined Identité Liberté since the party’s creation. The coalition is obviously still in its embryonic stages because it was formed hastily due to the snap election, but it has come to fruition. Remember that no party has ever come to power alone under the Fifth Republic. The Rassemblement National has clearly understood that allies are essential to securing a future majority. It would be a sign of political maturity to maintain and strengthen this coalition for future elections.

We share the most fundamental objective with the Rassemblement National: the desire to save France, particularly by halting mass immigration. However, we defend our respective political philosophies, priorities, and program proposals. I would particularly like to bring in and represent an electorate that aligns with the RN’s objectives, but may not fully identify with them or their platform. It is less about “unification” and more about achieving common goals by pooling our strengths to put an end to the Left and to Macronism allied with a pseudo-Right, while maintaining our nuances and expressing our distinct positions. Just look at the evolution of the centrodestra coalition in Italy—that is our model.

There is actually more consensus than division. The primary concerns of the French, especially those on the Right, are cultural insecurity, purchasing power, the collapse of public services and educational standards, and mass immigration. Most citizens also feel that ‘life was better back then’ and that their children will have a lower quality of life than they did. These issues are interconnected, particularly when it comes to immigration, which has dire consequences for society as a whole. Over 70% of French people believe there are too many immigrants.

Differences on the (French) Right primarily stem from the hierarchy of priorities, not division over fundamental values. So to win, we must present a coalition capable of offering a common program that addresses all these concerns. What makes us distinct is that we are against welfare dependency, advocate for a fiscal shock and economic liberation, remove barriers to innovation, and resist the deconstruction of our civilizational identity. We can assure voters who are particularly concerned with these issues that we will defend them within the framework of a coalition.

Islamism is fundamentally both the ideological and expansionist expression of this socio-religious dimension of Islam—which I also refer to as the “Islamization” of our societies. When the wearing of the veil becomes widespread, when we see the emergence of the abaya, or when the halal business sector booms, we see clear signs of Islamization, largely driven by the groundwork laid by Islamist organizations.

We are not a party defined by religious affiliation. We are not a confessional party. But there is no denying that Christianity is part of our identity and shapes our relationship to the world, being intrinsic to European civilization, and Catholicism to France in particular. I have said this incessantly since I first became involved in politics: the Republic is secular, but France is Catholic. It is Catholic in its history, in its traditions, in its very essence, in its soul.

Even if the entire French population were to become de-Christianized, we would remain a society deeply imbued with this religion that has shaped us for 1,500 years. Our understanding of humanity, our relationships with others, and our way of existing in the world are all fundamentally Christian. This does not mean that one must be Catholic or go to mass to be French! It is simply a social and anthropological reality, and in France, we have a right of pre-eminence to this reality, which is also, more broadly, that of our Christian civilization.

There have long been significant shifts from the Left to the Right, primarily among working-class voters abandoned by the Left. These groups were the first to feel the socio-economic and security impacts of mass immigration. While we continue to see some modest movement in this direction, broader awakenings are occurring in various sectors, including public education, as immigration and woke ideology affect everyone in profound and tangible ways. The largest reservoir of untapped voters remains on the Right, particularly among center-right individuals who abstained in the second round of the recent legislative elections, refusing the so-called ‘barrage’ against the Right but not yet ready to vote for the national camp. These are either voters more attuned to economic issues, awaiting real fiscal and entrepreneurial liberation, or abstainers who feel politically unrepresented. Our task is to engage with them and bring them back into the fold. That is the role we aim to fulfill.

It simply means unapologetically embracing being right-wing. We want a classical conservatism that seeks to protect what our ancestors built so painstakingly, and which modern deconstructionists seek to dismantle. This includes affirming natural order and immutable principles.

In practical terms, it means supporting families and standing firm on biological realities, and reminding people that a man cannot become a woman, and vice versa. It means valuing work as a path to personal freedom and rejecting the nanny state, which replaces organic communities and solidarities with sterile bureaucracy. National solidarity must, by definition, prioritize nationals. Practically speaking, it means reminding citizens that rights come with responsibilities.

It also means reducing the tax burden because we have the highest tax rate in the EU and one of the highest in the OECD. Public spending accounts for nearly 60% of our GDP. Our pension system is stretched to its limits, and paradoxically, French retirees often live better than the working population. Meanwhile, undocumented migrants can access free dental surgeries, cosmetic procedures, even organ transplants—all funded by French taxpayers who must pay for their own care. Concretely, this translates to returning the fruits of labor to the French people by lowering taxes, duties, and social charges while cutting public expenditures. This will liberate the economy and restore economic justice.

The year 2027 is an opportunity to seize power and reverse the trajectory imposed by decades of socialism and cowardice. My primary goal is to save France—by combating mass immigration, wokeness, and the deconstruction of our civilization.

Achieving this goal requires building a coalition of national unity. I intend to play an active role in this, both electorally—starting with the 2026 municipal elections, where we will field candidates within a broader coalition—and intellectually, by championing a “civilizational Right” that is authentically and unapologetically conservative. This perspective will balance various tendencies within the coalition, enabling us to unite a majority of French citizens.

As for the long term, it’s difficult to say. It is harder to predict in this age of rapid historical acceleration. Politics is the realm of the unpredictable. This is why consistency in one’s convictions is absolutely essential. What I can say with utmost certainty is that I will continue to fight for what I believe is right.