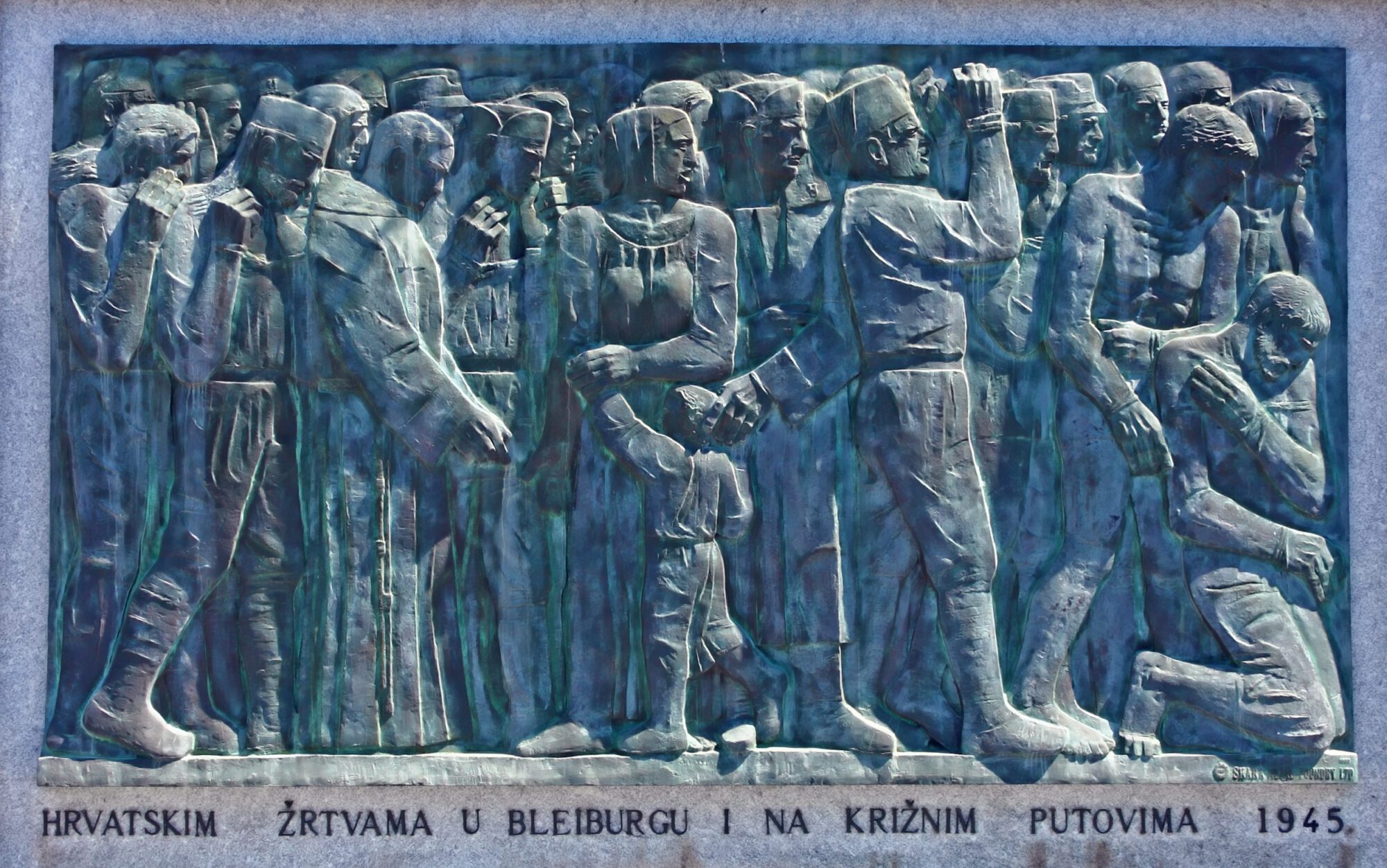

The Bleiburg Massacre refers to a series of killings carried out by Tito’s Yugoslav partisans which occurred in May 1945, immediately following the end of World War II in the European theater. Initially, Nazi-allied German and Balkanic troops had retreated towards Bleiburg, a town on the border between Austria and Slovenia, to seek refuge under British protection, together with a large number of people fleeing the communists. The British, however, sent them back south in a forced march that delivered them to be massacred at the hands of Tito’s partisans. The massacre has become a sensitive issue of dispute, with some calling for more recognition.

The majority of the victims were Croats and Slovenes, with communities of ethnic Germans and Italians also being greatly affected. Communist revolutionaries used foibes, deep sinkholes found in karst, to dispose of the bodies of perceived enemies—many of whom were still alive when dropped into the geologic cavities. Victims included both military personnel and civilians; men, women, and children.

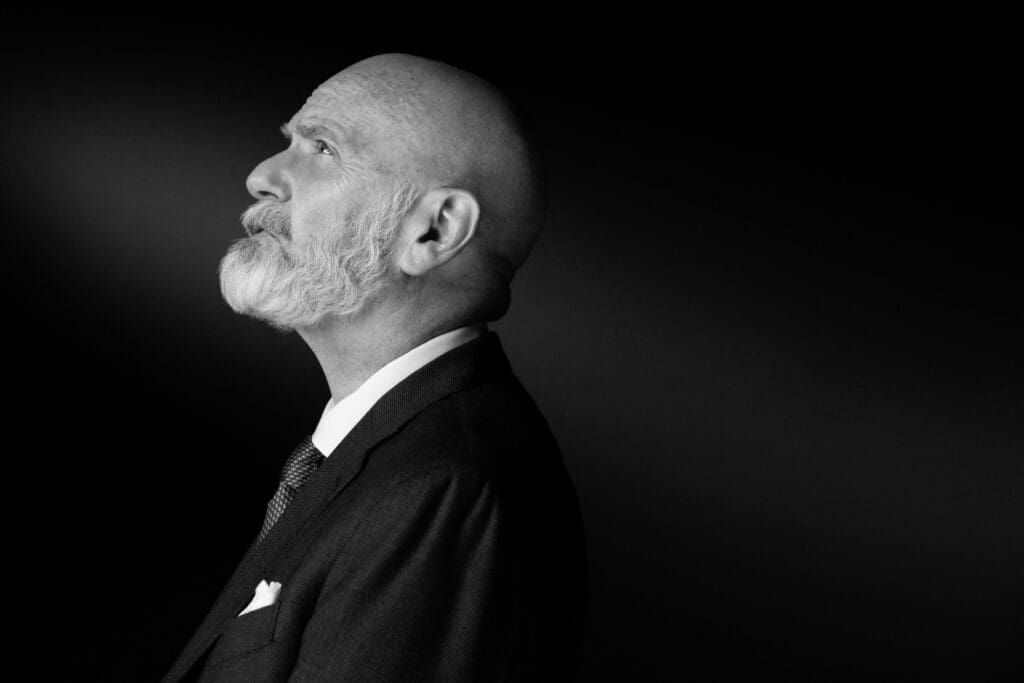

Historian Álvaro Peñas presents his analysis of the nature of the massacre, its impact on current affairs, and the dangers of historical revisionism.

Álvaro Peñas is an editor at deliberatio.eu, contributor to Disidentia, The European Conservative, El American and other European media. He is an international analyst, specialized in Eastern Europe, for the television network 7NN and an author at SND editores. He has published an updated translation of Buried Alive. Huda Jama, Tito’s Worst Crime by Slovenian historian Roman Leljak.

How many people were killed in the Bleiburg massacre?

It is very difficult to establish the total number of victims killed by the partisans between May and June of 1945, besides the fact that historians, depending on their origin or ideology, give very different figures. In my opinion, the number that comes closest to reality is the 80,000 victims reported by the Austrian historian Michael Portmann. However, to this day, graves are still turning up, especially in Slovenia, with hundreds and thousands of corpses, and the number could be as high as 100,000.

Why did the Allies deny refuge to people persecuted by the partisans?

The fate of the refugees, both soldiers and civilians, was decided at the Yalta Conference. Stalin demanded the surrender of all Soviet citizens who had fought with the Germans, and the same yardstick was applied to ‘Yugoslav’ citizens. At first, when the first soldiers and civilians arrived in Bleiburg, Austria, the British welcomed them and promised that they would be taken to Italy, but trains took them back to Yugoslav territory. In other cases, the British refused to accept the surrender of the new arrivals and allowed the partisans to take them prisoner. This went on for several days until Field Marshal Harold Alexander ordered that no one was to be surrendered against their will and that the soldiers were to be treated as prisoners of war. Later, the British would excuse themselves by saying that Tito had promised humane treatment for the prisoners.

Was ethnicity an important factor in the massacre?

In addition to an ethnic conflict, we are talking about a civil war. The partisans were mostly Serbs, but there were also Croatian communists, like Tito, and Slovenes. The victims were mostly Croats and Slovenes, but there were also Bosnian Muslims (at that time Croats), Serbs and Montenegrins. However, the ethnic factor of this crime would be decisive in the subsequent disintegration of Yugoslavia.

Ethnicity also played a role in two other cases, that of the German minority in Slovenia and that of the Italians in Istria and Dalmatia. 60,000 Germans were killed, half of them women and children, and the remaining half million deported to Austria, and of the 90,000 German soldiers imprisoned by the partisans, 16,000 died in Yugoslav concentration camps. The crimes against Italians, the “Foibe,” began during the war, in 1943, and continued right up until 1947, when more than 300,000 Italians left Istria and Dalmatia. Between 10,000 and 15,000 Italians were murdered and thrown, sometimes still alive, into natural graves.

How would you explain the brutality of Bleiburg? Why were the victims considered such irredeemable enemies of the new communist state?

The war in Yugoslavia was a partisan war, a brutal war, in which massacres and reprisals were the rule, not the exception. However, at Bleiburg the communists eliminated their real opponents, those who had fought them during the war, and also all those they considered to be their ‘class enemies:’ bourgeois, businessmen, clergymen, and all those who might oppose the new communist regime. After the Bleiburg massacre and the death marches to the concentration camps, the survivors had to face rigged trials that usually ended with death sentences or long periods in prison and, of course, confiscation of property.

What responsibility did Tito himself bear and what evidence do we have of it?

Bleiburg was a continuation of the crimes of the partisans in the war. It was a perfectly organized and planned massacre, despite the fact that attempts have been made to present it as the action of hotheads who were driven by the desire for revenge. There is even an order, whose authenticity is doubted by many historians, dated 14 May 1945, in which Tito orders that the prisoners not be executed. But it was Tito himself, in a famous speech delivered in the Slovenian capital, Ljubljana, on 27 May 1945, who made it clear that the order, if it ever existed, was nothing more than a dead letter:

As for the traitors to Yugoslavia in general, and in each republic in particular, they are a thing of the past. The hand of justice, the hand of retribution, our hand, the hand of our people, has reached them. Only a small number have been able to slip through our hands.

To believe that Tito was unaware of or disapproved of massacres of such magnitude is completely absurd. The Yugoslav communists were fervent Stalinists, and the Stalin of Yugoslavia was Josef Broz ‘Tito’.

Tito still enjoys a positive reputation in the West, how do you explain this fact?

Yugoslavia moved away from the Soviet orbit and that made it a ‘potential ally’ of the West. Thus, its crimes were forgotten out of sheer political expediency, as happened in the case of the Katyn [massacre] with respect to the responsibility borne by Soviet authorities. Tito benefited from that and was received by numerous Western leaders, such as Queen Elizabeth II, and was even decorated by Italian President Giuseppe Saragat, who awarded Italy’s highest distinction to the man responsible for the murder of thousands of Italians. To give us an idea of his positive image, Richard Burton played him in The Fifth Offensive. The silence about his crimes, which to this day remain unknown to most Western audiences, and the idea that he achieved the miracle of keeping Yugoslavia united and overcoming interethnic hatreds, continue to make Tito a popular figure.

What effect did the massacre have on the stability of the Yugoslav state: was what had happened known, despite official silence?

After committing their crimes, the communists went to great lengths to conceal them. Some of the execution sites were turned into rubbish dumps, others, such as the Macesnova Gorica abyss, where the exhumation of more than 4,000 victims was completed in mid-October this year, were mined and dynamited. For example, it took months of work to access the Huda Jama mine in 2009, the so-called ‘cave of horrors.’ Of course, the dictatorship forbade talking about what had happened, and the testimonies of the few survivors who went into exile were disqualified as ‘fascist’ propaganda. The terror unleashed in Bleiburg made witnesses unwilling to talk and the crime remained hidden for 45 years.

Do the Bleiburg massacre and similar crimes still have an effect on former Yugoslav societies?

Of course, the crime is still the subject of confrontation between the former Yugoslav republics and between political parties. Former Slovenian Prime Minister Janez Jansa told me that in this case, it is the descendants, and political heirs, of the executioners who do not want to forgive the victims. A memorial was erected in Bleiburg in 1987 and Croatia began officially commemorating the victims in 1995. The use of Ustasha symbolism by some attendees has caused problems with the Austrian government and has served as an excuse for anti-fascists to try to boycott the celebration. In Slovenia, too, acts of remembrance are frequent, while in Serbia and Bosnia it is practically a taboo subject. In Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia-Herzegovina, a Mass in remembrance of the victims was held two years ago, sponsored by the Croatian parliament. The religious event was heavily criticized and surrounded by heavy security measures, and caused a split between the Bosnian Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church.

To mention more recent events, just two weeks ago the Minister of Culture of the Slovenian coalition government, the eco-socialist Asta Vrečko, posed, smiling, next to a statue of Tito, and the Social Democrats have paid tribute to Boris Kidrič, president of the first Slovenian government who, when told that the number of victims of revolutionary terror was too great, replied, “even if at the end of the struggle there are only five Slovenians left alive, it will be a complete victory for us as long as they are all communists.” In October the exhumation of the Macesnova Gorica abyss, with about 4,000 victims, was completed. When a request was made to the mayor of Ljubljana that the victims be buried in a cemetery in the capital, the reply of the mayor, the social liberal Zoran Janković, was that there would be no graves for “traitors” in the Slovenian capital. Bleiburg’s wounds are still far from being closed.

Would you highlight any particularly striking episode of current denialism?

I am very struck by the case of Italy and the Foibe. It was not until 2004, under the government of Silvio Berlusconi, that a day of remembrance was established on February 10th to pay homage to the victims of the murders and the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus. It took almost 60 years to officially recognize a historical fact, which has not yet been assumed by a good part of the Italian Left. As Tito’s partisans were communists, the crimes are minimized, reducing the number of dead significantly or claiming that all the victims were fascists and therefore deserved it, or even denied. In addition, monuments or plaques honoring the victims are too often vandalized. Unfortunately (and this also happens in Spain) there are first, second, and even third-class victims.

How do you think the issue of ‘historical memory’ should be addressed, what role should legislators play in this regard?

I think that ‘historical memory’ is becoming a weapon at the service of political interests. Spain is a good example of this. It is not possible to establish ‘memory’ when only the crimes of one side are talked about and those of the other side are hidden, minimized, or denied. That is not history, it is the revenge of the heirs of those who lost the war. But we can see other examples of historical memory that are equally shameful. In Russia, under penalty of imprisonment, one cannot speak ill of the performance of the Red Army during World War II. Here, a new historical memory is rehabilitating Stalin and many of the criminals of the NKVD. Of course, this also entails the concealment of their victims. In the city of Tver, two plaques dedicated to the Poles killed in Katyn were removed because of ‘historical controversies.’ We have also seen in occupied Ukraine how monuments to Holodomor victims are destroyed and statues of Lenin are erected. ‘Historical memory’ is used with convenience by the political power that follows Orwell’s maxim: “He who controls the present controls the past and he who controls the past will control the future.”

What positive effect can an authentic ‘historical memory’ serve?

A ‘historical memory’ without political conditioning and ideological passion could be positive. Of course, the first step would be to honor the victims, whatever side they are on, but the reality is that the conditions for this to happen do not exist. Today, only about twenty countries recognize the Holodomor as a genocide, and this despite the fact that the Russian invasion has significantly increased sympathy for Ukraine. We also have the Armenian genocide, from which more than a century has passed, which is recognized by only 31 countries.

On a personal level, how did you become interested in this topic?

It was two and a half years ago, following a publication on social networks by Giorgia Meloni. A foiba with 250 corpses, 100 of them minors, was discovered in Slovenia and the current president of Italy wondered indignantly how it was possible that the Left continued to deny the murders of thousands of Italians at the hands of the Yugoslav communists. She had heard of such crimes in the past, but had never investigated them thoroughly.

The Foibe massacre brought me to Bleiburg and into contact with the Slovenian historian, Roman Leljak, who was the first to point out the sites of many of the horrific partisan massacres back in 1989, such as Huda Jama. Leljak provided me with a lot of information on the subject and I translated his book Buried Alive into Spanish.