In the last two decades, dystopian novels and their cinematic spinoffs have flooded the market. Many of the novels—Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games, Veronica Roth’s Divergent series, etc.—are, in my view, largely derivative of Lois Lowry’s The Giver, a brilliant novel infused with what struck me as obvious religious overtones and a scathing critique of the commodification and cheapening of human life, all done allegedly in service of the common good. When I asked Lowry about this some years ago, all she said was that she hadn’t intended to project her own religious or political views onto the story, although she admitted that it was a subconscious inevitability.

Dystopian storytelling is all the rage at the moment because it is tapping into something many of us feel but often cannot articulate—much that is good, true, and beautiful is being kept from us. Most dystopian tropes explore common themes: the sense that things are being hidden; that the elites are against the common people; that those in power are acting against fundamental human interests; and, perhaps most importantly, that technology is being used to render populations subservient. In nearly every instance, those imposing tyrannical regimes on the masses believe they are doing so for their own good. As C.S. Lewis noted: “Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of the victims may be the most oppressive.”

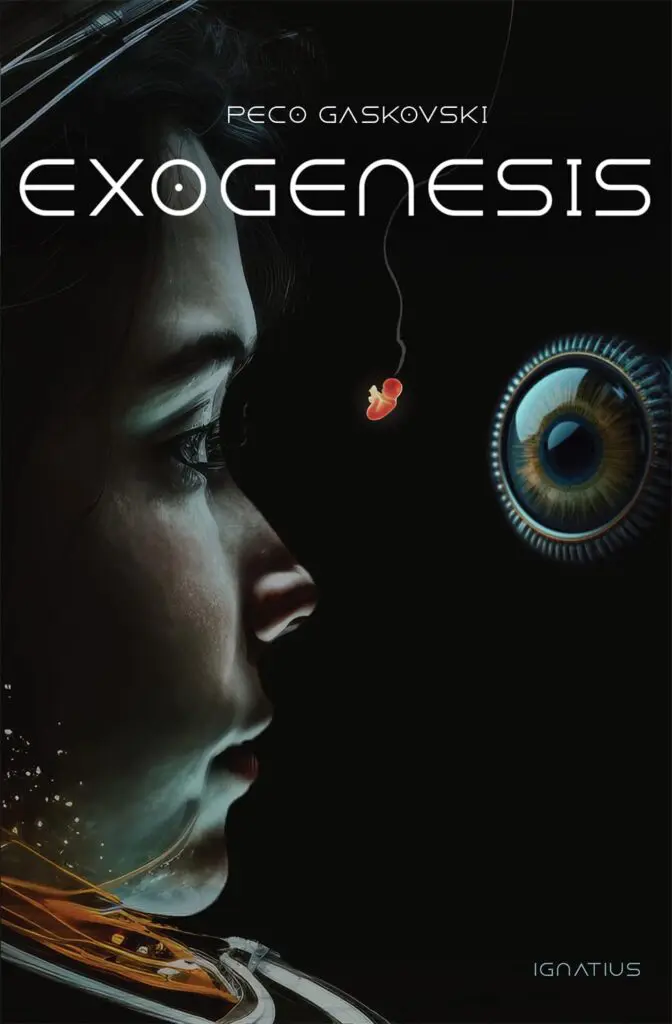

Peco Gaskovski’s new novel Exogenesis checks those boxes—and more. It is not a subtle novel. The story is based in Lantua, a “glittering thousand-mile metropolis where drones patrol the sky and AI algorithms reward social behavior.” It is the state that rose after the collapse of “Old America.” Citizens who conform to the regime are rewarded with staggering privileges; the poor struggle to rise through the “echelon system”; the population is rigidly controlled. Exogenesis refers to the process of growing embryos—selected carefully for genetic quality—in artificial wombs. Women do not give birth naturally in Lantua, and it is illegal to do so. Suffering is eliminated by the targeted use of therapeutic drugs. Human beings have in many ways merged with technology.

Outside Lantua, however, reside the Benedites, a rural religious people modeled on the Amish (their name a derivative of Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option.) The one-child policy meant to both limit the population and control their numbers is enforced at gunpoint. The main character of Exogenesis is Field Commander Maelin Kivela, who oversees the forced sterilization of Benedite teenagers with coldblooded efficiency. Kivela is totally committed to the technological civilization that grants her so many pleasures and privileges until a violent encounter with Benedite insurgents forces her to reconsider many of her assumptions—and in doing so, provokes similar reconsideration on the part of the reader. Gaskovski’s novel is a pointed cultural critique, but not a simplistic morality tale.

Peco Gaskovski took the time to answer my questions for TEC on his novelistic debut as well as his other writing projects. I sincerely hope to see much more from him.

The newsletter always hovers over the same ground—what it means to be human in the lengthening shadow of technology. What does it mean to be human when our mental focus is constantly fed through the paper shredder of our devices and our distracted minds are manipulated by algorithms? What does it mean to be human if our lives are online and our real relationships suffer? How might AI and biotech further impact or distort the essentials of human identity? I don’t have a formal philosophy. I write as a father who wants to protect his children and family, and as a person of faith who wants to protect his mind and spirit. I’m looking for hope.

Seventeen hundred years ago church leaders gathered to formulate the Nicene Creed, to stabilize our basic understanding of the Christian faith. Today I feel like we need a further creed, one that outlines the parameters of being human—which is a strange thing to say. It’s always been taken for granted that we know what a human is. But old assumptions are being uprooted. Transhumanism, or the idea that we ought to transcend human nature and perfect ourselves through technology, is seeping into our way of thinking. Two decades ago, Wendell Berry wrote that the next great division in the world would be between people who wish to live as creatures and people who wish to live as machines. That division is getting closer, and if it comes, the impact on human identity will be shattering.

In most every sense the ‘Machine’ is a cautionary concept: beware of the dark side of technology. I sometimes imagine the ‘Machine’ as a many-armed destroyer goddess: the arms are Big Tech, investment, political interests, transhumanist ideology, and credulous consumers.

I should say, I’m not anti-technology. I believe that as God is a primary Creator, we are sub-creators who desire, and should, reshape creation through invention. Sub-creation includes things like art, writing, music, and architecture, but it also includes technology and innovation.

The problem arises when our sub-creations—in this case tech—displace the Creator. This doesn’t happen because people are suddenly bowing down to their MacBooks or singing hymns to their iPhones. It happens because we are religious creatures by nature. Our spirit yearns for ultimate meaning and purpose and connection. When God is displaced from the center of our hearts, the yearning doesn’t go away. It seeks something else. For many that something else is technology.

I don’t think technology can satisfy that yearning, but it can provide a counterfeit experience that stimulates our passions and validates our egos. How do we respond to this? How do we stay human and centered in a true reality? I’ve been asking myself these questions for years. Exogenesis is one answer in fictional form.

I think it’s more the latter. The story is really about the present, disguised as the future, and some of the things we need to think about to avoid a technological dystopia. So, while like most novels there’s a plot, characters, and evocative settings—think Blade Runner meets the Amish—ideas are also quite prominent. That was a deliberate choice for me. I wanted the vital issues to be accessible, and for readers to come away from it not only feeling and imagining, but thinking.

For instance, the world of Exogenesis includes artificial wombs, the selection of human embryos based on polygenic profiling, the dissolution of mother, father, and family, and mass surveillance by artificial intelligence systems. All of these are future possibilities within our own world, some already emerging, and we need to be thinking about their moral implications now, rather than waiting for them to overtake us.

I agree some readers may see the society in Exogenesis as aspirational. That too was deliberate. I wanted readers to feel transported into this place, and to think, “You know, this isn’t too bad at all. I could be comfortable here.” Because that’s the temptation we’re all feeling today with technology. That’s the lure, the bait, the danger.

As for the Tower of Babel, every civilization eventually collapses. What’s unique about our time is that there are two varieties of collapse that we could experience. Imagine your son or daughter builds a big structure of blocks, and you accidentally bump it while walking by. The structure or parts of it will fall into ruin, so that what was previously ordered and livable is now disordered and chaotic. That’s one kind of collapse. It can happen to a society in various ways—war, disease, scarcity, environmental catastrophe—but it could also happen if we become too dependent on technology, too interwoven with it, and then something goes fatally amiss.

The second kind of collapse is that the block structure doesn’t get knocked over, but rather that the blocks begin to tighten up, like walls closing in around the people who live in that society. An example would be a technological system in which everybody is observed and monitored, and behaviors are micro-managed by increasing numbers of rules and prescriptive values, with punishments for those who don’t comply.

That too is a collapse, yet not of disorder, but rather the opposite: a collapse of hyper-order, one that over-regulates individual human life. The mega-city depicted in Exogenesis involves that sort of collapse; however, there’s enough comfort, security, and enticement that most citizens lap it up. I think it’s a collapse that the Western world is flirting with. Some are even suggesting that the only way to avoid a descent into disorder is to embrace hyper-order.

As a homeschooling family, our faith and relationships with each other have always been at the heart of home life. This foundation has shaped our approach to everything else, including tech. For the first twelve or thirteen years, it was easier to manage tech use, as the kids were younger, and we could set boundaries without much difficulty. We also placed great emphasis on books, spending time in nature and with friends, and free play.

Now that was back when many people still used flip phones and our home had only a single laptop. For a long time, my wife and I could depend on our personal discipline to regulate tech use in the family. Today, the situation is different. Our kids are older, the devices in our home are more numerous and powerful, and Wi-Fi is so ubiquitous and unlimited you can almost breathe it. The structures and pulsing signals of the ‘Machine’—I call it the Technopolis—are building up around us.

So personal discipline isn’t enough to manage tech in the family anymore. Our emerging solutions are focusing, instead, on regulating not just ourselves, but our physical environment. For instance, laptops can’t just lie around anywhere and be used anytime, but are restricted to certain times, and then must be returned to their storage places. We’re far from perfect in this, but I think this approach—a temporal and structural order that thwarts ‘Machine’ structures in the home—is more effective than expecting individuals to resist with willpower.

There are various blind spots. We might end up thinking that attending church online is the same as going physically, even though this places the Body of Christ within a ‘Machine’ framework. On a smaller scale, I’ve seen chanters reading liturgical texts off their phones. There may be times when digital conveniences make sense, but if the medium really is the message, then perhaps we need to rethink the structural presence of technology in the church as much as in the home.

Many of society’s moral narratives are also expressed through devices, although they don’t often target the devices themselves—but that isn’t surprising. We can’t expect the pot to criticize the potter or the oracle to speak against her own god. Meanwhile, these narratives often support technology as the primary solution for our problems, which can subtly shift even our spirituality in a transhuman direction. Why do we need Eternity if, one day, we might be able to upload our consciousness to a quantum computer?

As a result of all this, many of us have developed ‘Machine’ imaginations. If, from a Christian worldview, we want to un-‘Machine’ our minds, it might help by opening our imaginations to the nature of reality as expressed by that worldview. This could happen in different ways, like spending more time in prayer, or through meditation on Scripture.

For example, if God thinks and feels and speaks—if God has something like a ‘mind’—then maybe to be fully human means exercising our own mental functions, and not enfeebling them through excessive device use. Or, if God is face-to-face relationship as a Trinity, then our real center is not within us, but within the other—in our real relationships. And if God made the earth, plants, and animals, then maybe being human means staying physically close to these things.

All that might sound very basic, yet in all these areas—mind, relationship, nature, embodiment—the ‘Machine’ competes against God, by framing every part of reality as a biological mechanism or a simulation, to be manipulated according to our caprice. I think this is where the real battle is—a battle to answer the question, “What is reality?”

But this is not a question for Christians alone. It matters to all of us, and I think we need to wrestle with it in our families, our schools, even in our politics. We’ll come up with varying answers, but what matters is that we’re left with a robust moral awareness of the dark side of technology. Without that, the only thing left to wake us up will be suffering.

If by inspiration you mean other writers or writing, I’d say they’re eclectic—anything from classics to fantasy to scientific papers. I just finished re-reading Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and hung off almost every line. I frequently go back to Iain McGilchrist’s The Master and His Emissary, as it has illuminated so much about my own cognitive processes. The irony about all my reading is that most of it is done by audio books, as I’ve never been good at visually concentrating on written text—so that particular digital technology has been of genuine benefit for me.

As for other inspirations, they can come from anywhere. Writers are strange creatures, and I would never recommend trying to be one, since it’s mostly effortful and mostly unrewarded. However, it has one redeeming quality that overrides all else: it feels like home.

I spoke with author Michael O’Brien a few years ago in his garden, and he advised me to pray before I write, while I write, and after I write. I have always trusted this advice. I think all actions are spiritual actions, and that includes the words and ideas that well up from my imagination, are printed on paper or pixels, and that sink back into the imaginations of others. It’s a giving, and I want to give people something that will transport them, yet something they can trust. That doesn’t mean the writing is safe. It means, no matter what it does to you, it hopefully leaves you a little more human in the end, a little more grounded in what’s real. Writing and reading involves a relationship between two people—author and reader—and in that relationship, technique is secondary, and reality is everything.

I tend not to talk too much about my writing while it’s still cooking, but I’m always working on fiction, and lately on non-fiction, so it’s fair to say you can expect more.