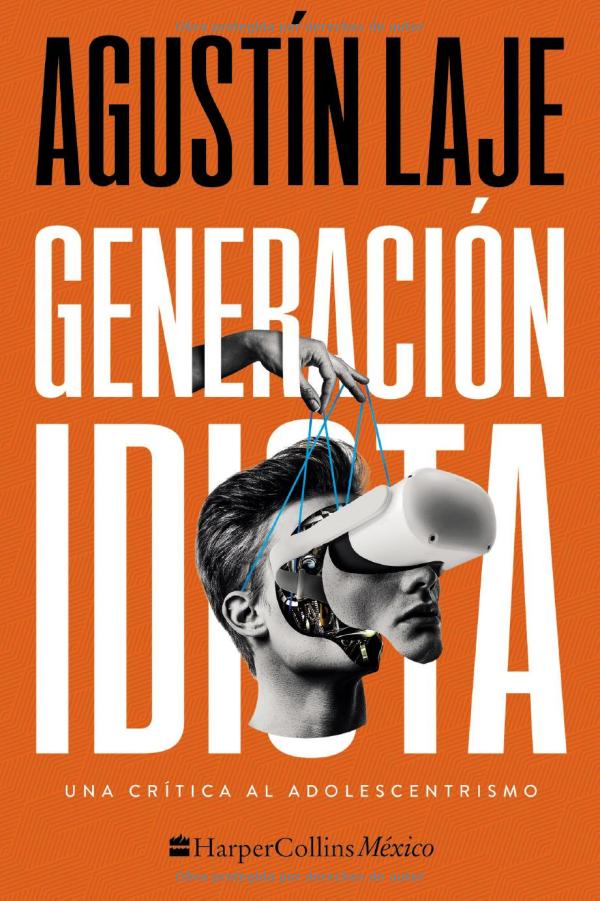

Agustín Laje holds a degree in political science from the Catholic University of Córdoba, in Argentina. Founder and director of the Fundación Centro de Estudios LIBRE, he is a columnist in different media and author of the books Los mitos setentistas (2011), Cuando el relato es una Farsa (2013), El libro negro de la Nueva Izquierda (2016), co-authored with Nicolás Márquez, and La batalla cultural. Reflexiones para una Nueva Derecha (2022). We recently spoke about his latest book, Generación idiota: Una crítica al adolescentcentrismo.

Generación Idiota points out the path taken in many Western societies, sick with ‘wokism,’ towards the “adolescent society.” In addition to being idiotic, could we speak of a lost generation?

The idiot generation is lost in its inability to look beyond its own narcissistic navel. This unbearable narcissism, often disguised as ‘woke’ politics and progressive posturing, produces an absolute closed-mindedness. We see this in the most varied phenomena, such as the ‘safe spaces’ of certain universities, the characterisation of any idea that does not conform to progressive hegemony as ‘hate speech,’ the dominance of self-perception as the measure of reality, and the consequent end of truth as a discourse that we project towards a reality located outside of us (hence the notion that we live in a ‘post-truth’ society).

This hatred for diversity of thought, of beliefs, of ideas, and of political positions, has wrecked the idiot generation for good, as it seduces itself into believing that diversity advances simply because we can dye our hair green, feel like we are in the wrong body, or sleep with someone of the same sex (and celebrate it for a whole month every year).

In a society based on ‘adolescent centrism,’ what place do old age and childhood have?

Absolutely none. On the one hand, adolescent centrism is based on a general rule, which we could summarise as “new is good, old is bad.” Old age is presented to an adolescent-centric society as something essentially bad, in many different but similar senses: the old is out of fashion; the old is morally outdated, due to the acceleration of social change; the old is technologically outdated, in a society marked by exponential technological change; the old, in its proximity to death, recalls the finitude of life in a society where death is tantamount to the absolute end.

With regard to childhood, many sociologists and political scientists in recent decades have denounced a kind of infantilising process. But the infant is too innocent and pure to be confused with the adolescent-centric idiot that dominates our cultural and political environment. The infant, as its very etymology indicates, lacks a voice. The infant is deprived: he cannot self-determine, nor does he even pretend to do so. On the contrary, the adolescent-centric idiot claims complete self-determination, but leaves it incomplete or mutilated, since the component of individual responsibility is always missing.

The current obsession with encouraging children to explore gender and sexuality (which is becoming more and more radical every day) stems from the special contempt that the adolescent idiot has for the idea of a phase of life in which the individual of the human species lives under the rule of family authority. Remember all those feminist theorists of the 1970s, for example, who wanted to annihilate all family authority over children.

The eternal adolescent would represent, as you rightly point out in your book, the Nietzschean ideal of the ‘superman’ or the ‘new man.’ Is Greta Thunberg the best example of the adolescent society, and the social networks its ‘kingdom of heaven’?

She is a very relevant example because of the magnitude of her mediatisation. What Greta reveals is something that is actually outside of her, namely that our culture is willing to believe that a teenage girl is going to be the saving principle of a climate apocalypse. Greta herself is a very uninteresting character. Look at her when, at last, she has been questioned in the streets by journalists with whom she had not pre-arranged her interview: the poor girl could not answer a single one of the intelligent questions put to her.

What is interesting, in any case, is to see how the elites use the image of adolescence, embodied in Greta, to direct the masses towards certain expectations, themes, slogans, emotions, and so on. All this is not only done with the power of social networks, since Greta, strictly speaking, is not a network character: she is a character constructed by the main multimedia corporations.

There is a video from a few years ago where a young white man of 5’6” presents himself as a 5’8” Asian woman and a majority of university students accept his perception of reality. After changing our sex at will, is it time to change our age? Does the cult of adolescence open the door to trans-age?

The dissolution of sex as a principle of reality certainly opens the door to the dissolution of any other identity characteristic, whatever it is. Think of it this way: if the reality of sex can collapse under the pressures of gender ideology, even though it is so rooted in the materiality of physiological, anatomic, and genetic realities, then what is to prevent any other identity category from collapsing? Indeed, while age depends on the passage of time, there is something about age that seems much less rooted in materiality than sex. Thus, there is even less preventing the reality of age from dissolving than there is preventing the dissolution of sex.

The same exercise can be done with any other feature of personal identity, for example, nationality. If nationality is politically defined by the state, and is therefore much less material (and therefore self-evident) than biological sex, why shouldn’t it too be dissolved and subjected to the self-definition of the individual, via the self-perception of national identity? It sounds absurd, but this is essentially the same logic.

You devote a chapter to fashion and the veneration of the new. But fashion and the new are increasingly ephemeral. Are dissatisfaction and consumption, so typical of the adolescent, the stimuli of the idiot generation?

Indeed, fashion is increasingly ephemeral, and that is why it is so important to account for the emptiness experienced by so many teens. Fashion only exists to the extent that it changes; it depends, so to speak, on a permanent self-sabotage. When everyone ‘becomes fashionable,’ fashion can no longer fulfill its promise of giving some semblance of identity.

You speak of dissatisfaction, typical of the adolescent, and I think that’s the way it goes, although I would complement it with the problem of identity. Dissatisfaction with respect to what? Dissatisfaction with respect to the self; with respect to who or what I am. Adolescence, according to Erik Erikson, is a stage characterised by the absence of a well-defined identity. The adolescent ‘stumbles around’ because he does not yet know who he really is. Well, I believe that exactly the same thing is happening in our culture, only at a sociological level.

The current idea that everyone must ‘invent’ their own identity is creating too much social stress, too much discomfort. Perhaps we were freer and more comfortable when certain identity traits were already taken care of beforehand.

Does the entertainment world represent the role of the new heroes and saints of the idiot generation?

That world has, so to speak, become ‘democratised.’ The great promise of the current fame system is that anyone, without any mediating criteria, can also be famous. The democratisation of fame destroyed the criteria by which one used to become famous (exceptional skill, genius, sapience, heroism, sainthood, and so on). The great promise of social networks and their systems based on likes and followers is precisely that: to be able to be famous while being as ordinary as I am.

However, this democratisation of fame has been followed by an intensification of our relationship with celebrities themselves, in which we are more influenced by them than ever before. We live with them all day, every day. They are everywhere. That’s why they are now called, rather, influencers. In a way, we accept that they influence us: moreover, we want to be influenced by them because, in an adolescent-centric culture, we all wish one day to be famous too.

The current vice-president of the Spanish government, Yolanda Díaz, has presented her new political project with the “objective of making people happy.” We don’t know what drug, or what Soma, she is going to use, but don’t all these good intentions hide the worst of totalitarianism?

It hides what I call in my book the ‘nanny state,’ which is, in effect, a kind of light totalitarianism. The state seeks to take over the whole of man’s life: his decisions, his tastes, his beliefs, his ideas, his relationships, his family, even his very happiness! We have already seen this, for example, in Venezuela, where Chavismo created the ‘Ministry of Happiness.’

The new thing about the nanny state is that it treats its subjects as if they were, precisely, adolescent idiots. It no longer robs them of their freedom in the name of the ‘class struggle,’ the ‘spirit of the people,’ the ‘national spirit,’ or whatever was used as a liberticidal excuse in the totalitarianisms of the 20th century. Rather, today it robs them of their freedom in the name of their own happiness.

This idiotic movement comes from above, from the elites. Is the New Right the rebellion, the answer against this totalitarianism?

In fact, that is how I end the book, by proposing a model of rebellion against the empire of the idiot and, of course, its puppeteers: the elites who use it. If there is anything that reproduces the status quo, the established order, it is globalist progressivism. Look at how comfortable all these neo-leftists feel in the forums of the global elites; how comfortable they feel with the output of the big entertainment corporations; how comfortable they feel with the messages usually offered by the stars of show business; how comfortable they feel with the foundations of the meta-capitalists; how comfortable they feel with the most powerful international organisations on the planet; how comfortable they feel with the ‘new values’ of multinational companies, which sell ‘woke’ ideology in each of their advertisements; how comfortable they feel in the power stations of the academic establishment; how comfortable they feel, in short, with everything that holds political, social, and economic power.

In the face of this reality, the New Right, more than simply conservative, is entirely subversive. Indeed, it dreams of subverting the domination of these elites. Hopefully that dream can, to some degree at least, become a reality.