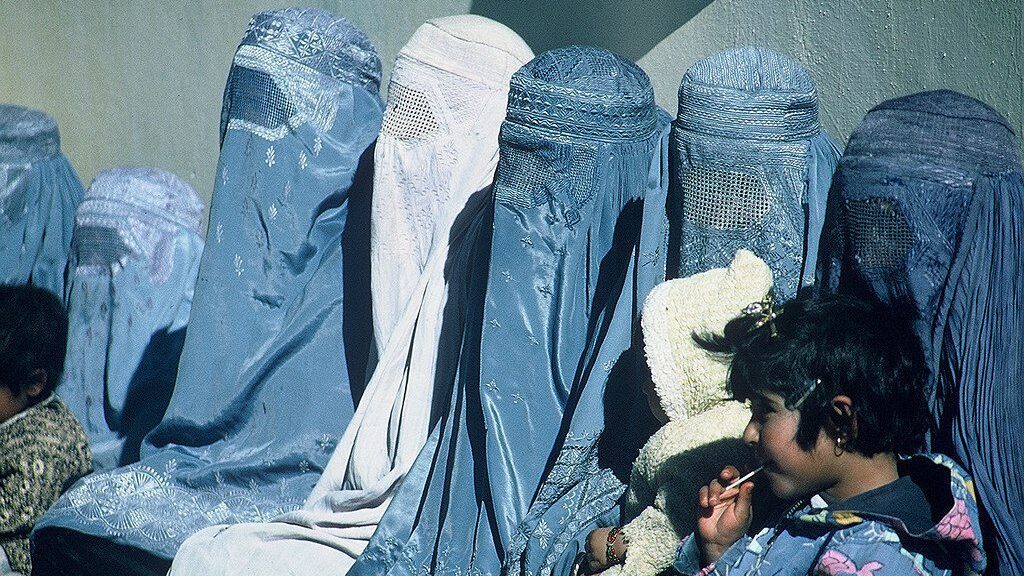

Photo: Nitin Madhav (USAID), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) has ruled that each of the 20 million women in Afghanistan would qualify for refugee status inside the European Union—without the need for an individual application.

The decision came when two separate legal cases in Austria were combined and referred up to the higher-level ECJ. The Austrian Administrative Court faced a lawsuit brought by two Afghani women who were previously refused refugee status, but granted subsidiary protection. The pair had arrived in different circumstances, in 2015 and 2020, but were initially deemed not to be at risk of persecution in Afghanistan since both claimed to have fled Iran prior to arrival in ‘safe’ EU countries (with one having never even lived in Afghanistan).

The ECJ was asked to rule on the question:

Can the numerous forms of discrimination that women in Afghanistan are exposed to be considered together and do they constitute persecution under the Geneva Refugee Convention?

Whereas an “act of persecution” may sound like a single form of aggression or control, the court came to redefine such an ‘act’ as an accumulation of multiple discriminatory measures. By listing the Islamist domestic policies of the Taliban, which returned to power in 2021, the whole package was interpreted as impairing human dignity “through its cumulative effect”.

The charge sheet against the Taliban is compelling. The report cites a “lack of any legal protection against gender-based and domestic violence,” along with forced marriages, the obligation for women to cover their bodies completely and to cover their faces, the restriction of access to health facilities, the prohibition or restriction of the exercise of gainful employment, the denial of access to education, the prohibition of playing sports, and the denial of participation in political life.

With few reasons to doubt this description, the question remains whether the ruling—accepting any and every Afghani woman without the need for an individual asylum application—is the right response.

Hypothetically, this decision could increase the population of the EU by 20 million at the stroke of a pen. Yet one part of the cumulative “act of persecution” identified by the ECJ is strict rules on male guardianship, which restricts the unaccompanied movement of women, especially overseas. Likewise, it sets a legal precedent for would-be female refugees to argue that their own home states, such as some Gulf Cooperation Council members, create an equally hostile environment.

No indications yet on how many ‘transgender’ Afghan men will start identifying as women to secure their EU asylum status without having to be individually vetted.