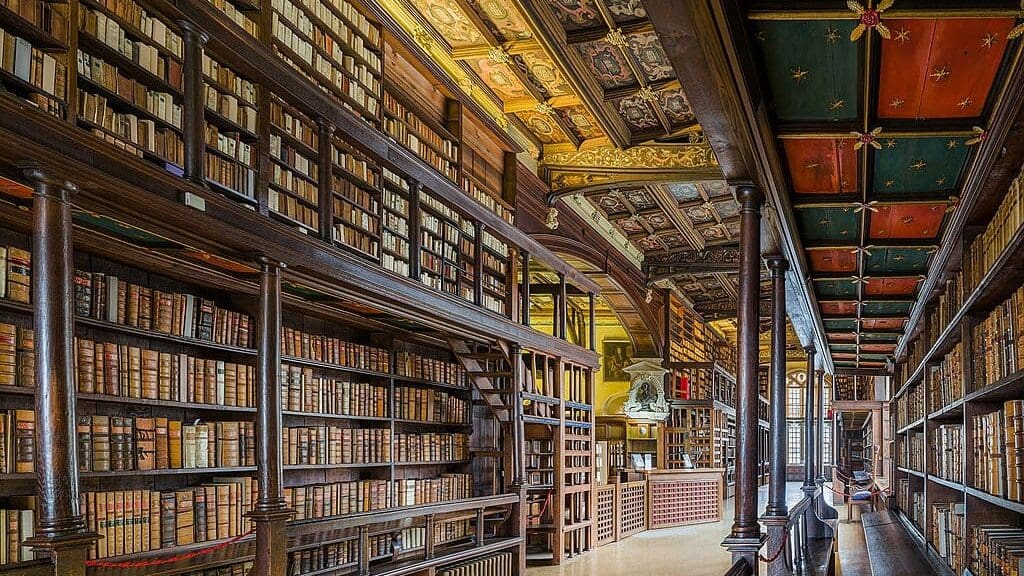

Photo: Diliff, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

A core institution within British higher education is falling short of its founding ambition of helping female academics and students—and may actually be making matters worse. That’s according to Heather McKee, Convenor of Student Academics for Academic Freedom (SAFAF), in a report published on Monday, August 20th. At the very least, it suggests that mission creep by the organisation means it no longer addresses its original goals—while creating new and unnecessary structural problems.

Setting out at first to increase the role of women in academia, the original charter programme is now subsumed within Advance HE, a charity and professional membership scheme. From this platform, Athena Swan now seeks to advocate for “all gender identities,” while committing “to considering the intersection of gender and other factors wherever possible.” It does so by setting up an extensive framework where a compliant university can volunteer to meet Athena Swan charter benchmarks and, after approximately two years of application and inspection processes, be awarded Bronze-, Silver- or Gold-level status.

Drawing on the Higher Education Student Statistics UK 2021/22 (released in January 2023), the author shows that the proportion of females in the UK studying the ‘hard sciences’ (except for engineering, which has 78% male recruitment)—and dominating veterinary sciences, psychology and subjects allied to medicine—remains broadly static.

A more damning picture emerges from the figures for female professionals when using a sample drawn from Athena Swan charter-marked universities (grades Bronze to Gold). McKee shows that while roughly half (ranging from 48% to 60%) of non-professorial staff are female, the proportion of female professors and other senior academics at such institutions lags behind, typically by at least 20% (i.e. a range of 17% to 25% shown in the report). The author also references a significant gender pay gap.

In short, women based at Athena Swan institutions appear to experience stagnation at work, even as their employers are garlanded for supporting their careers. Meanwhile, to achieve charter-mark status, universities are expected to commit serious time and resources to a burgeoning semi-regulatory body with a potentially controversial agenda.

McKee also worries about the sheer expense of the process. A recent justification—cynics might say alibi—used by the Labour government for dropping a new law on free speech in higher education was the potentially ruinous cost of fines for universities which failed to uphold free speech. In contrast, the resources dedicated to achieving an Athena Swan award are seen as value for money—regardless of the real position of women in the UK (and, increasingly, global) higher education.

Incidentally, if ideological capture—such as replacing women with ‘gender identity’ in its charter—raises your hackles, wait until you realise that the Advance HE website still links to the discredited organisation WPATH for advice on how to teach on ‘trans’ matters. Lest we forget, WPATH treats ‘eunuch’ as a ‘gender identity,’ reinforced by a folder on the website housing ‘erotica’ i.e. child pornography, depicting the castration of boys.

This is all some way from 2005, when the Scientific Women’s Academic Network (SWAN) and the Athena Project collaborated on a charter promoting women’s representation in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) and women’s employment in research and higher education. By 2015 its charter had expanded to include humanities and social science subjects, accompanied by a broader range of ideological commitments.

Current parent group and supersized quango Advance HE was formed when the Higher Education Academy (in which the present author held ordinary membership) merged with the Leadership Foundation for Higher Education and the Equality Challenge Unit in 2018.

The Athena Project should not be confused with the women’s music project of the same name.