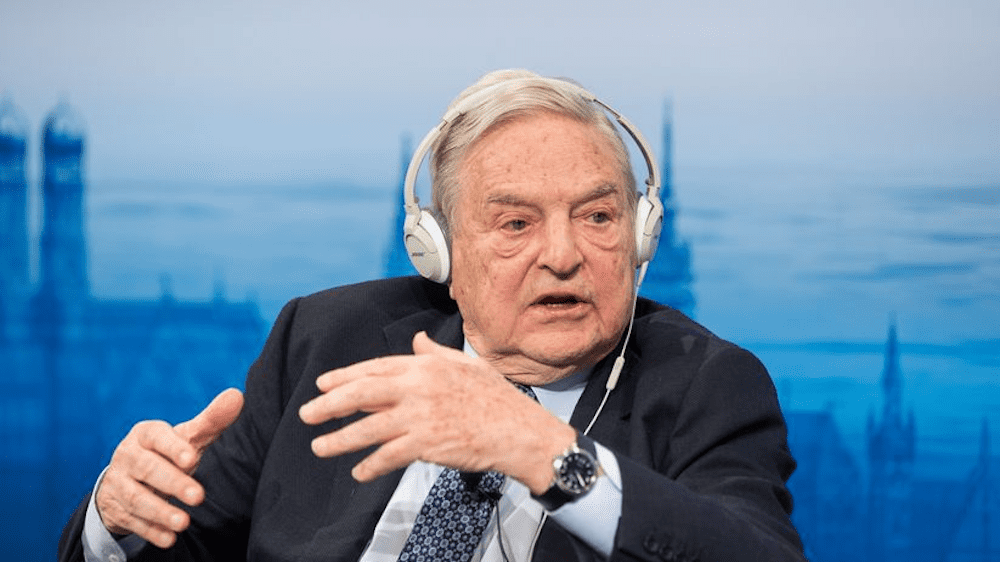

George Soros

Over the weekend, India’s Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar struck back at billionaire investor George Soros over disparaging comments the latter had made about India’s current leadership. Jaishankar called Soros an “old, rich opinionated” and “dangerous” person and accused him of “scaremongering.”

The 92-year-old hedge fund tycoon and known backer of leftist and open-border causes stirred the pot by accusing Prime Minister Narendra Modi of holding non-democratic views. Consequently, George Soros is increasingly finding himself considered persona non grata by India’s government.

The Soros-funded Open Society Foundations group has been accused of meddling in countries averse to its founder’s ideology. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s government effectively halted the group’s operations in their country through 2018’s ‘Stop Soros’ act. That same year, the Open Society Foundations moved their international operations and staff from Budapest to Berlin. Before his landslide second re-election and subsequent approval of the bill, Orbán said:

We know by name who they are and how they work to transform Hungary into an immigrant country. That’s why we drafted and submitted the Stop Soros bill which qualifies immigration as an issue of national security.

India, where Soros’ Open Society Foundations has been active since 1999, might now contemplate a similar move.

“Essentially, Mr. Soros at the Munich [Security Conference] said that India is a democratic country,” but that he “does not think that the prime minister of India is a democrat,” the Indian dignitary noted.

In his February 16th address to the conference, Soros called India “an interesting case,” as it formally is a democracy, but—Soros claimed—its leader, Narendra Modi, is not. “Inciting violence against Muslims,” he added, “was an important factor in his [Modi’s] meteoric rise.”

In his reply to Soros, made during a February 18th session with Australian Minister Chris Brown at the Raisina-Sydney Dialogue, Jaishankar added that a few years ago, at the same conference, Soros “actually accused us of planning to strip millions of Muslims of citizenship. That, of course, did not happen … it was a ridiculous suggestion,” Jaishankar said while referring to the Citizenship Amendment Act, which critics have described as an “anti-Muslim law.”

It is estimated that about two hundred million Muslims, most of whom identify as Sunni, live in India. Making up 15% of the population, it is the country’s largest minority group by far. Their close proximity to the nation’s Hindu population, which makes up about 80%, has been a cause of religious tensions that have often escalated to violence.

Soros also said that while Modi “maintains close relations with both open and [what Soros deems] ‘closed’ societies,” he “buys a lot of Russian oil at a steep discount and makes a lot of money on it”—an obvious effort to discredit Modi’s government by linking it to the Kremlin.

In addition, Soros predicted that, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s fate was “intertwined” with that of Adani Enterprises’ owner Gautam Adani (calling them “close allies”), the recent turmoil in Adani’s business empire may open the door to a “democratic revival” for the country. Following a January 24th report on Adani Enterprises by Hindenburg Research, alleging improper use of offshore tax havens and stock manipulation, the group’s seven listed companies lost $120 billion in market value collectively.

Modi, Soros prophesied, would “have to answer questions from foreign investors and in parliament,” and this would “significantly weaken” his “stranglehold on India’s federal government and open the door to push for much needed institutional reforms.”

“You have to understand what this [Soros’ comments] actually means,” Jaishankar suggested to his audience. “I could take the view that the individual in question—Mr. Soros—is an old, rich, opinionated person, sitting in New York” who “still thinks that his views should determine how the world works.”

Careful to not allow his observation of Soros as old, rich, and opinionated to be dismissed, Jaishankar observed that “such people actually invest resources in shaping narratives.”

“People like him,” Jaishankar went on, “think an election is good if the person they want to see, wins, and if the election throws up a different outcome then they will say it is a flawed democracy and the beauty is that all this is done under the pretense of advocacy of open society.”

Stressing that Indian voters should decide on “how the country should run” instead of Soros, he referred to India’s past experience with colonialism, which made it aware of “what happens when there is outside interference.”

Jaishankar concluded that “a debate and conversation” must be had on democracy, which would entail grappling with the question of by whose values democracy is defined as the world eventually turns less “Euro Atlantic.”