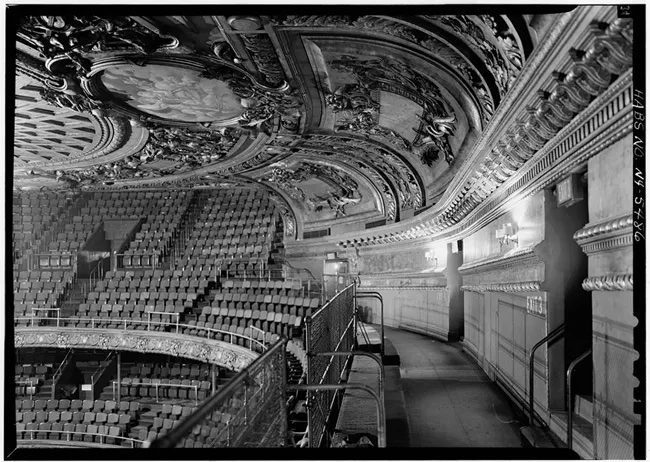

The interior of the Metropolitan Opera House, with the “Golden Horseshoe” partially visible.

NPS Photo / Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress.

“Strike a blow for civilization!” invited an advertisement for subscriptions to New York’s Metropolitan Opera in 1978. At the time, that bold phrase drew rebukes from old-guard Met patrons, who thought it too brash for their genteel opera company, then approaching its centenary. Just a year before, the Met abolished its white tie dress code for opening night, a convention only a few reactionary holdouts still observed. A little over a decade earlier, the Met had opened its ‘new’ house at the Lincoln Center, an arts complex whose development drove the revitalization of New York’s rundown Upper West Side neighborhood. The ‘old’ Met, at Broadway and 39th Street, which was demolished, was sorely missed after a long Golden Age of outstanding performances by exceptional artists. But much hope was invested in the company’s future. Alas, by the late 1970s, the Met was plagued by poor attendance, distressed finances, crippling labor problems, aimless leadership, public apathy, a sharp decline in artistic quality, and a national socio-economic meltdown.

Fast forward four decades and all of these problems have returned with a vengeance under the dubious administration of Peter Gelb, the Met’s general manager since 2006. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic closed the Met for eighteen months and inflicted an estimated $150 million in losses, the company had fallen into a middle-aged torpor. Star-quality performances were fewer and farther between. New productions flopped with depressing regularity. Ticket sales routinely languished at 70% capacity or less. Tensions between management and the Met’s nineteen labor unions began to flare up again. A rising cohort of philanthropists began devoting their largesse to macro issues like climate change, global poverty, and ‘social justice’ rather than to preserving their grandparents’ foreign-language musical theater. Who could blame them? With already limited attention spans, the millennials starting to take over family foundations or realize vast wealth in tech and finance were the first generation in modern times to receive little or no education or exposure to the arts, foreign languages, or anything worthy of regard in the increasingly woeful and irrelevant academic humanities. Unimaginative marketing campaigns foundered. Ticket prices soared. In 2009, the opera house’s iconic murals by Marc Chagall were pledged as collateral to secure a line of credit to finance debt that to this day remains outstanding.

Just as in the 1970s, New York itself began to fall apart under Bill De Blasio’s disastrous mayoralty, which presided over rising crime rates, decaying infrastructure, looming financial crises, and general urban decay that did little to encourage people to spend long nights out at the theater. All the while, the strained American middle class—and even a significant part of the upper class—ceased to be aspirational in taste or cultural interests. Professional working hours dramatically increased, along with expectations, competition, stress levels, exhaustion, and all the infelicitous intrusions of post-modern life. Popular culture became more debased even as it became universal and ever less avoidable. Ideals of beauty were assailed by resentful assertions of gritty ‘relevance,’ squalid relatability, and dour egalitarianism. At home, isolated and atomized, consumers embraced Netflix and the like as a tepid but acceptable fallback.

On the eve of the pandemic, worse portents emerged. ‘Woke’ ideology asserted strict speech and behavioral controls over how American professionals conducted themselves, and even over how they may have conducted themselves decades before. At the Met, this resulted in the purge of longtime music director James Levine, superstar singer Plácido Domingo, director John Copley, and tenor Vittorio Grigolo, all of whom were defenestrated amid sexual harassment allegations of which there was little or no proof.

As the pandemic set in, the racial reckoning that followed the death of George Floyd—a serial criminal and drug addict—drove a cultural campaign against classical music for its ‘whiteness,’ a characteristic that became tantamount to grave offense, if not an outright crime. Leading cultural commentators—including the New York Times’s chief classical music critic Anthony Tommasini—seriously argued that race should outweigh talent in staffing American orchestras. The Juilliard School was condemned by its own students as a “systemically racist” institution. As early as 2015, the Met had ostentatiously ended the use of blackface in depicting the title character of Giuseppe Verdi’s Otello, a deletion many audience members found baffling, and which European opera administrators continue to find absurd. In September 2021, the Met rescheduled its planned opening night new production of Verdi’s Aida—its first performance since March 2020—to accommodate the accelerated premiere of the black composer Terence Blanchard’s abominable Fire Shut Up In My Bones, a trite musicalization of black Times columnist Charles Blow’s self-indulgent, oversharing, and painfully dull memoir of his depressing childhood. Sales were so poor that hundreds of tickets to the opening night gala—normally a sold-out fundraiser with stratospherically high prices—were reportedly sold for $25 or just given away. The major criterion for the choice of work was its composer’s race. The Met’s revenues in 2021-2022 were $40 million lower than before the pandemic closure.

As the pandemic receded, the Met’s administration hoped its fortunes would revive, especially as it compliantly adhered to woke political mandates coursing through urban American life. Indeed, it continued to impose a mask mandate up to 1 November 2022, long after that questionable measure had been removed virtually everywhere else.

It was horribly wrong. The pandemic, racial tensions, and blue-state politics only accelerated the decline. Despite De Blasio’s replacement by Eric Adams, a former police officer, the city’s race-driven crime wave actually worsened in 2022, with almost every category of serious crime registering an increase of more than 30% over the previous year. Over half a million New Yorkers are believed to have left the city—so many that New York state lost one of its Congressional seats. Even in the absence of pandemic restrictions and indignities, demographic indicators suggest that departures have accelerated. A disproportionately large number of those who left New York were high-income earners who escaped state and local taxes that are now the highest in the United States. More than a few former Met patrons now enjoy a vastly better quality of life in friendlier environments like Florida, where income and inheritance taxes are banned by state constitutional amendment. Not coincidentally, Florida’s arts scene is thriving and rapidly expanding as New York’s suffers and contracts. Well-to-do New Yorkers who remain show no sign of rallying to safeguard either the city’s general well-being or its struggling cultural institutions, as their predecessors heroically did on both counts in the late 1970s.

In the woke atmosphere prevailing in the city, the Met’s politicized management practices caused the loss of more high-quality artists. In March 2022, the company severed relations with the superstar Russian soprano Anna Netrebko—probably the only remaining artist who could sell out the house—and the celebrated Russian conductor Valery Gergiev because they refused to denounce their government over the war in Ukraine, even though doing so in Russia is a crime for which they could face up to 15 years in prison. In inquisitorial fashion, the Met did not punish them for anything they had said or done, but frighteningly for what they had failed to say upon their employer’s demand and—likely illegally—on the basis of their nationality. The German bass René Pape, another longtime box office draw, also seems to be out for good after stating a controversial opinion of gay pride parades. They and other purged artists still have thriving careers elsewhere, and devoted American fans can make their way to hear them perform in what now feels like much freer societies while the Met languishes with lesser talent.

Now in its second full season after the pandemic, Met audiences continue to decline. A recent revival of Verdi’s Don Carlos, in a production that was much heralded when it arrived just last season, only filled about 40% of the house. Astonishingly, its director, David McVicar, who has produced 13 mostly lackluster Met productions, continues to hold sway as the house’s unofficial chief producer, alongside such other mediocrities as Michael Mayer, Phelim McDermott, François Girard, and Bartlett Sher, whose talents—such as they are—lie mainly in dramatic theater. Meanwhile, such stellar opera directors as Tobias Kratzer, Krzystof Warlikowski, Calixto Bieito, and Kasper Holten—sometimes provocative and edgy but at least imaginative and well-versed in their craft—are only known to New York connoisseurs through European reports.

Last week, the Met took advantage of the distraction-filled time between Christmas and New Year to announce that it still faces major financial challenges. Among the more glaring statistics was that it expects only 19% of its tickets to be sold via subscription this season, down from 45% in the early 2000s. Pledged financial commitments have been delayed, and a recession looms. Gelb declared that next season the number of performances will be reduced by about 10%. He also announced that the Met is in the process of cannibalizing $30 million of its endowment to meet operating costs—a gigantic ‘no-no’ in American nonprofit management, and a step the Met avoided even in the darkest days of the pandemic.

One might imagine that the Met may have learned a powerful lesson from its present plight and uncertain future, but unfortunately not. Incredibly, Gelb still retains the confidence of the Met’s Board of Directors, who seem unfazed by the company’s many woes and impervious to any suggestion that after 16 stale years of poor leadership it might be time to hazard something new.

Instructively, in the late 1970s that is precisely what the company did under general manager Anthony Bliss, an unsentimental patrician with a background in Wall Street law and World War II military intelligence who watched the bottom line carefully but entrusted artistic decisions to Levine and delegated considerable management authority to the practical Joseph Volpe; who worked his way up from the Met’s carpentry shop and later succeeded Bliss. Within only a few years, the Met’s finances rebounded. Levine built the Met orchestra into one of the world’s finest ensembles—so superb that it started giving regular orchestral concerts outside the opera house. The company’s productions surged in quality and popularity to become world-renowned and powerfully enduring in popular memory. Neglected composers and works were regularly staged in a valuable vein that might well have continued. Singing at the Met was the international gold standard of vocal performance. Attending—if one could get tickets—was the epitome of Manhattanite social ambition. The house stayed out of politics, but both contributed to and benefited from New York’s Renaissance under Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, an opera lover who occasionally appeared on stage as a supernumerary in Met productions. For good reason, Volpe, who retired in 2006, titled his memoirs The Greatest Show on Earth.

Today, this all seems like a fairy tale from the mythic past. The men who made the Met great again are gone, succeeded by a farrago of underwhelming personalities, limp publicity campaigns, and preachy woke sloganeering. Gelb’s solution is to double down on what he imagines to be promoting ‘social relevance when his job is to entertain. Having recently scored some success with Kevin Puts’s opera The Hours, based on a popular book and film that interweaves three stories about neurotic middle-aged women (and, yes, one could pick a better way to spend an evening out of a hat), he has determined to offer yet more such works in the hope that they will prove popular enough to draw new audiences. Every opening night from now on, he will menace audiences with a contemporary opera, starting next season with Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking, a searing indictment of the death penalty. The 2023-2024 season will also feature the Met premieres of an opera about the radical black Muslim activist Malcolm X and John Adams’s El Niño, an opera-oratorio about the birth of Christ partly told through Latino voices. Revivals of Fire Shut Up In My Bones and The Hours are also planned. One can already see $25 ticket ads furiously flung about to try to fill row after row of empty seats.

Gelb really should know better. Recently, he signed a petition imploring Arts Council England to reverse its decision to slash funds for the English National Opera, London’s century-old second opera company. ENO, which performs all works in English to promote accessibility, had presaged the Met’s new course by presenting a great deal of contemporary opera. The reason for the defunding, which its director claims imperils its existence, is that the financial results of staging the very repertoire Gelb now plans to embrace are too meager to be sustainable. In what should be another giant red flag, ENO has also recently been giving away free tickets to people under 21, offering steep discounts to audiences aged 21 to 35, and pandering in other humiliating ways, such as creating an opera for TikTok. Why Gelb thinks imitating this disastrous course would work in New York remains a puzzlement, but he will doubtlessly feel the baleful effects for however long he lasts.

Met music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin, who succeeded Levine as music director but has far less authority, stature, and talent, appears to agree with Gelb’s new course and says he wants “everyone to feel welcome at the Met … I don’t want anyone to say, ‘The Met is not for me.’” Unfortunately, many already have, and many more will join them if the company continues with its disastrous new course.