Fawlty Towers: The Play Misfires in London

The play’s primary draw seems to be a nostalgia for a fading Middle England.

The play’s primary draw seems to be a nostalgia for a fading Middle England.

The visuals barely pass as a recognizably traditional setting while also failing to offer any symbolic interpretation of the work.

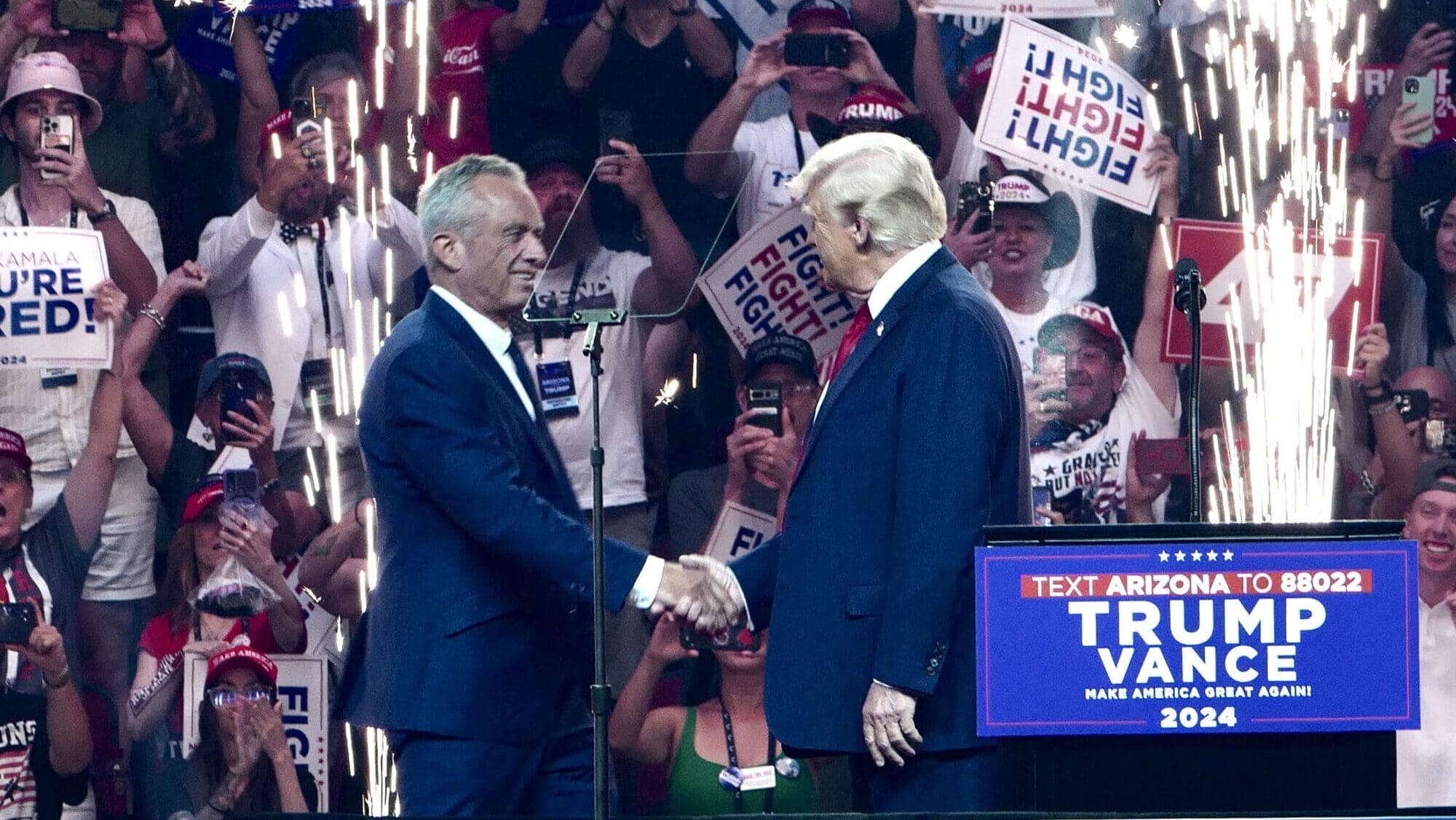

Just after the Democratic National Convention ended, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. endorsed Trump, casting their alliance as “a unity party.”

The production signified an evolution in the robust career of superstar Russian soprano Anna Netrebko.

La Scala’s ballet troupe is among the best in the world and has lost no luster in this revival of a production it has been showing for thirty years.

Jules Massenet’s opera invites dreamy fantasies of a lost and better world.

The gloomy production is a poor platform for superstar soprano Lise Davidsen and a generally stellar cast.

In his debut performance of the title role, Gábor Bretz is superb in the Hungarian State Opera’s production of Mussorgsky’s enduring classic.

The WNO scores a success, delighting audiences with its freewheeling, Jazz-age New Orleans take on Offenbach’s Songbird.

This year’s Vienna Philharmonic U.S. tour sees memorable performances of Bruckner’s and Mahler’s Ninth Symphonies.

To submit a pitch for consideration:

submissions@

For subscription inquiries:

subscriptions@