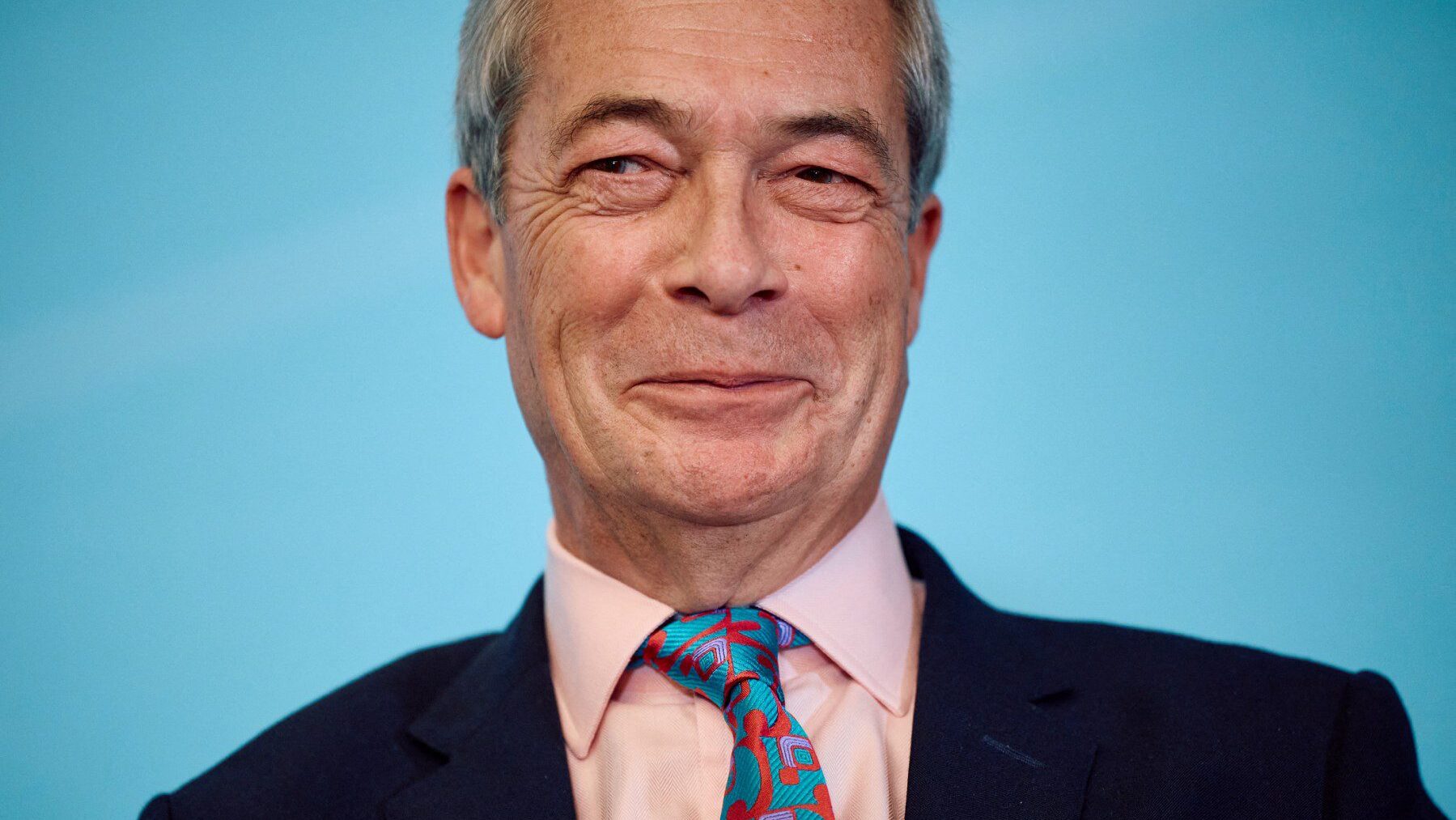

Photo: BENJAMIN CREMEL / AFP

The momentum in Britain’s July 2024 general election lay not with Labour—whose victory was shallow, brought about only by the total collapse of the Tories—but with Reform UK. Now Nigel Farage’s upstart party is surging in the opinion polls, and even the liberal media has been forced to stop sneering at the idea that Farage could win the next parliamentary elections, due by 2029.

Barely six months after the dullest UK general election campaign in memory, the rise of Reform UK threatens to bring boring British politics to life. It is a sure sign that no corner of Europe is now immune to the populist revolt against the old political establishment.

In July, Reform, contesting its first-ever general election, won just over four million votes—14.3% of the total. That translated into only five Members of Parliament—less than one per cent of the total seats—due to the UK electoral system. Now Reform is regularly polling well over 20 per cent, in a three-way contest with Labour and the Conservatives—and the polls probably underestimate its support.

The dynamic is clearly with Farage, who recently revealed the remarkable fact that Reform’s membership has now topped that of the Tory Party. As he put it, “The youngest political party in British politics has just overtaken the oldest political party in the world. Reform UK are now the real opposition.”

This is an historic moment.

— Nigel Farage MP (@Nigel_Farage) December 26, 2024

The youngest political party in British politics has just overtaken the oldest political party in the world.

Reform UK are now the real opposition. pic.twitter.com/t8SOHThxp3

At the start of 2025, it looks almost as if the ailing mainstream parties are doing what they can to boost Reform.

Labour’s Keir Starmer has shown himself not just to be a bad prime minister but a deeply unpopular one, too—the most unpopular new PM in recent British history, which takes some doing.

Faced with the momentous challenge to rebuild a self-destructed brand, the Tories’ position has not improved since party members late last year chose Kemi Badenoch as their leader. Even when she has tried to say the right things about fighting the culture wars or stopping mass migration, Badenoch remains badly hampered by her role in previous failed Tory governments and her own centrist parliamentary party’s lack of enthusiasm for radical change. As chairman of the conservative Bow Group Ben Harris-Quinney told europeanconservative.com, the Tory party’s “utility and therefore very existence remains in question.” By the end of 2024, Badenoch appeared increasingly shrill and desperate, making unfounded claims that Reform has falsified its membership figures and even effectively calling on the media to censor Farage, accusing the likes of GB News of creating “a haven for my critics.”

All this sets the stage nicely for Reform, though without guaranteeing its success. The possibility of the social conservative vote being split between the Tories and Reform again, allowing Labour to hold onto power, remains real, though Reform is also making impressive inroads into the Labour vote in working-class ‘Red Wall’ constituencies

A continued close association with the British farmers’ revolt will certainly help to maintain momentum, along with the party’s obvious lead on the issue of immigration. (At least 450 illegal migrants crossed the Channel on Christmas Day alone, and more than 35,000 came via this route over the whole year, which Labour ministers are working hard to portray as a success! The figure is dwarfed by that for legal migration, and Reform MP Rupert Lowe has done much to get the establishment to admit the wrongs of all this.)

In 2025, Reform should be able to make hay on issues such as free speech and cancel culture, the betrayal of Brexit, the culture wars against woke, and international issues. Critics say Reform also needs to address its positions in other areas—particularly with regards to social issues. Former Tory MP Miriam Cates pointed out that “its primary criticism of the Conservative Party has been that it is no longer conservative”, yet three out of the five Reform MPs recently voted in favour of assisted suicide in a ‘free’ parliamentary vote with no party whipping. Farage, who Cates also credits with making “welcome interventions on strengthening the family,” voted against legalising euthanasia.

Reform is also engaged in an ongoing process to make the party both more professional and democratic, with Farage himself admitting that “amateurism” let the party down at the 2024 election.

There will be plenty of opportunities for checking Reform’s development through 2025—major polls, by-elections for the House of Commons and local authority elections, where Labour allows them to take place—and it will be worth keeping an eye on its success in attracting young voters and major donors, both of which are essential ahead of 2029.

If Reform continues its advance this year, Farage will be within sight of leading the genuine ‘political revolt’ he promised when he returned as party leader before the general election. Boring British politics could be about to get even more interesting.