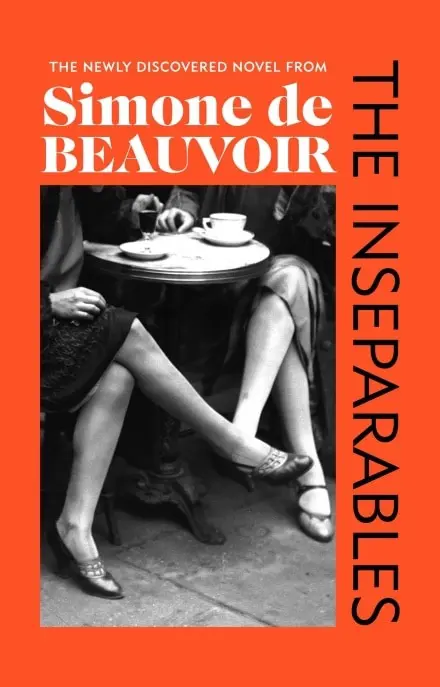

Simone de Beauvoir’s childhood friendship with Élisabeth Lacoin has long been a matter of interest for her admirers. Nicknamed ‘Zaza,’ Lacoin died too young, but her life was long enough to make a lasting impression on de Beauvoir. She memorialised her lost companion with a novel, written in 1954, decades after the events upon which it is based.

Jean-Paul Sartre was not impressed when he reviewed the first draft of The Inseparables. De Beauvoir agreed and set the manuscript aside, leaving it to languish unread among her private papers. Finally published in 2021, it is only now that people can judge whether discarding it was wise or premature.

‘Premature’ has been the unanimous verdict of the left-wing critics who run today’s literary scene and who have not stopped gushing about The Inseparables. However, they fail to notice that, released today, the novel lacks the appearance of freshness which it would have enjoyed—as all de Beauvoir’s other books did—if it had been published in the ’50s. Despite its modest merits as a work of art, The Inseparables promotes a view of the world which is now boringly conventional, although much-loved by the Left: the idea that religion, nationalism, and patriarchy are the greatest threats to human freedom. Under these conditions, heroism can only consist of repudiating these alien ‘power structures’ and striving for a society where individuals can express themselves in their full, authentic glory. It is hard to avoid suspecting that the book is being praised for the simple reason that it recoats this clichéd philosophy with de Beauvoir’s illustrious name.

Indeed, de Beauvoir possessed a strong personality and a formidable intellect. She took no prisoners when attacking Western capitalism and the married family. Regrettably, these intellectual standards were relaxed when her attention turned, though it rarely did, to the evils of Communism. She belonged to that generation of Marxist intellectuals who were more scandalized by the age of sexual consent laws in France than by mass murder in China or Cambodia. However, her unique achievement as a thinker was to put a feminist spin on the existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre, with whom she shared an open and lifelong sexual relationship.

“Existence precedes essence,” the premise of Sartre’s philosophy, posits that the purpose of life is not determined in advance of our existence, either by God or society. Instead, life’s essence begins from the recognition that we exist as free beings, and it is this freedom that individuals must exercise if they are to give unique, authentic purpose to an otherwise meaningless life. De Beauvoir’s contribution was to encourage women to be especially passionate in answering this call to adventure, rather than surrendering to the ready-made costumes—marriage, motherhood, and monogamy—that the ‘patriarchy’ had forced on them. The basics of her feminist existentialism, well developed by 1954, are visible throughout The Inseparables.

De Beauvoir writes with a captivating immediacy, although she is not immune to the temptations of cliché. “Softened smiles,” “her shining eyes,” “life without her would be death”—such stock phrases are not used as sparingly as they should be, especially by an existentialist philosopher who taught us to prize authentic expression above all else.

The Inseparables centres on the teenage years of Sylvie and Andrée, two friends who represent de Beauvoir and Zaza, respectively. Like most children, Sylvie is naturally impish and even rebellious. But these fiery traits, Sylvie tells us, give way to the cooling effects of French patriotism and the Catholic faith, both imposed on her from outside. To use Sartrean terms, Sylvie submits to the “bad faith” sources of meaning on offer, in the form of faith, flag, and family. Indeed, Sylvie’s father tells his daughter that French defeatists should be shot. Her mother is, accordingly, less-than-subtly dismissed for always saying “the same thing as Papa.” Taken together, they are caricatures of the unthinking patriot and the unquestioning second sex, trapped by the sham mindsets which they fail to recognize as such. At this point, not even Sylvie is aware, let alone trusting, of her freedom to reject the false offerings of tradition. She has yet to answer the existentialist calling to create authentic forms of purpose for herself.

All of this changes when Sylvie meets Andrée, her lively classmate who puts the frigid atmosphere of their Catholic school to shame with her playful and unpredictable spirit. The more obedient Sylvie is overawed by Andrée’s apparent commitment to living on her own terms. She is also dazzled by Andrée’s cultivation of the higher pursuits: her voracious consumption of the literary classics and her musical talents. De Beauvoir leaves Sylvie swooning over her new companion. Reaching for yet more clichés, Andrée’s prodigious character is praised as “a gift she had received from heaven.”

Unsurprisingly, the joyful simplicity of their childhood bond is soon complicated—by adolescence, erotic love, and Sylvie’s loss of faith. But more than anything else, their bliss is disturbed by the pressures of a censorious, intolerant adult world. These pressures merely perplex the sceptical Sylvie, now a determined atheist. However, they are enough to sap Andrée, who out of all the qualities which had made her most admirable as a child, clings to religion. Having been headstrong and grand, Andrée now appears vulnerable and petite as she makes excuses for the controlling behaviour of her pious mother, rationalizing her actions by stating “She’s meant to look after my soul.”

A skilled storyteller, de Beauvoir certainly knows how to take care of the reader. But this talent can have the deceptive effect of making trivial feelings appear worthy of serious attention. As the story swells to its tragic crescendo, sentimental outbursts start getting the better of narrative subtlety, with such passages as “Poor Andrée! All she wants is a little happiness on this earth!” Such a cliché would at least be fitting if Andrée’s fulfilment were being thwarted by persecution, death, or some other unspeakable evil. In actual fact, she is being obliged by her parents to wait a bit longer before marrying the man she loves, while he attends to his agrégation exams and she boats off to Cambridge. This is hardly Casablanca, yet Ingrid Bergman and Humphrey Bogart seem a couple of stoics next to de Beauvoir’s overwrought heroines.

In fact, the closest we get to oppressive cruelty in The Inseparables is parents taking an excessive, perhaps unhealthy interest in their daughters’ love lives. Sylvie and Andrée enjoy remarkably privileged childhoods, receiving a first-rate education and being permitted all manner of girlish freedoms. Being deprived of complete sexual autonomy is about as oppressive as ‘bourgeois morality’ gets—and the young are free to reject it in any case, as everyone does at the Sorbonne. In fact, only someone shielded by the cushions of such a bourgeois upbringing would have the narcissism to believe this even approaches genuine oppression.

“She’s their slave, I thought,” says Sylvie about Andrée, adding “Not a single move she makes isn’t regulated by the mother or grandmother.” Such is the nature of parental and religious guidance, both of which Sylvie blames for darkening Andrée’s life, lamenting “how she’d fought against her mother for the right to follow her heart and conscience; all her victories were poisoned by remorse, and in the least of her desires she suspected a sin.” Bear in mind that Andrée, at this point, is barely in her twenties.

There is no question that de Beauvoir took the frivolities of youth too seriously. It is not a coincidence that she fought, along with Sartre and Foucault, to abolish the age of sexual consent laws in France. We can now point to The Inseparables as further proof of her sentimental view of adolescence. If de Beauvoir’s elders can be accused of mistaking repression for virtue, then she and her intellectual peers were blind to the fact that over-indulgence is not freedom, but, instead, ranks among the most irresponsible forms of neglect. Adolescents have never been freer than they are today to engage in unfettered self-expression, be it on Tinder, TikTok, or Instagram. They have also never been so unaccountably miserable.

De Beauvoir is capable of subtle poetry, but even these moments can be undermined by highly direct, on-the-nose messaging. As Andrée’s romantic frustrations reach an alarming pitch, Sylvie describes meeting her in a café where “all around me perfumed women ate cake and talked about the cost of living.” This is a great sentence, except that the implied contrast of these conventional housewives with Andrée’s more extraordinary nature is then ruined by this bald statement: “Andrée was fated to be like them. But she was nothing like them.”

As a private manuscript, The Inseparables is a sincere, heartfelt tribute to a lost childhood friend. But its literary merits are limited—the greatest proof of this being that Simone de Beauvoir herself, the pre-eminent feminist icon of the 20th century, deferred to the patriarchal advice of Sartre and kept this attempt at self-expression hidden in her chest of drawers.