Snap the Whip (1872), a 30.5 x 50.8 cm oil on canvas by Winslow Homer (1836–1910), located at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

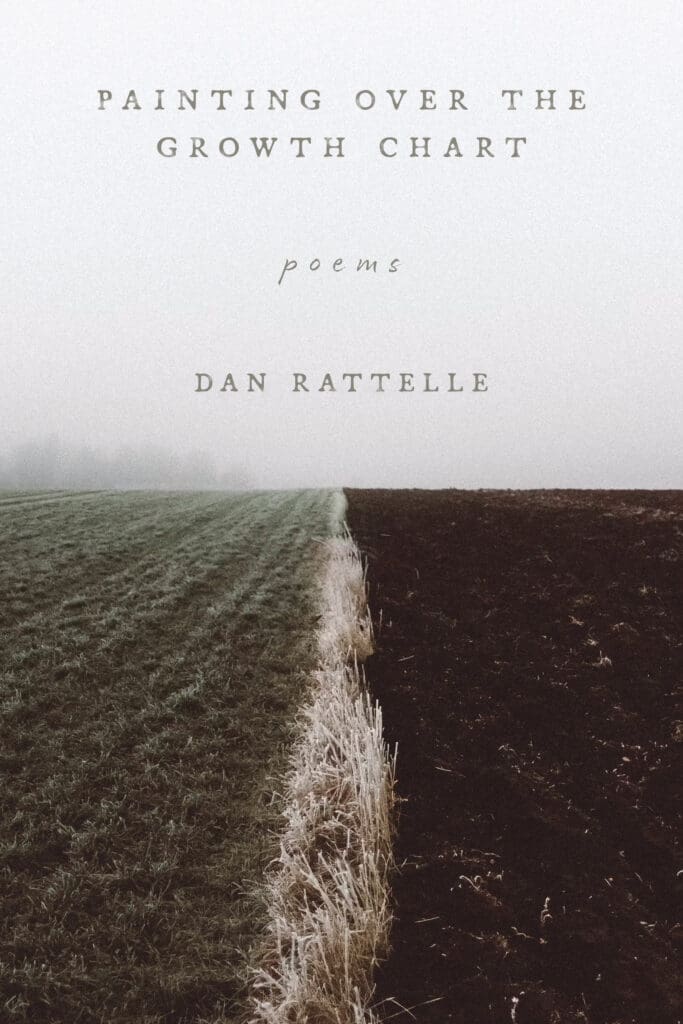

Some poems have titles so exceptional that they almost surpass the content of the poem itself. Wallace Stevens had a rare talent in this regard, giving us “The Idea of Order at Key West,” “The Emperor of Ice-Cream,” and “Tea at the Palaz of Hoon.” With Painting over the Growth Chart, Dan Rattelle has shown himself every bit the equal of Stevens. The title—both of his debut collection and one of the poems within it—is richly evocative. Indeed, it summons in a few words an experience so complex that any number of descriptive terms might justly be employed—wistfulness, contentment, anxiety, sadness—only to fall short of the fullness of the scene itself. The cover of the book, then, augurs well: after all, poetic craft is as much about knowing what to depict as it is about the craft of versification itself.

The promise of the cover is fulfilled by the poems within, for Rattelle’s artistry carries through the entire collection and never wanes along the way. The book’s four parts (sequentially titled “The Meeting House,” “The Commonwealth,” “Hinterland,” and “The Republic”) each speak not only of a place but of an idea about a place—a projection of abstract order onto a physical location. Stevens, who wrote “The Anecdote of the Jar,” also knew all about the projection of order onto natural spaces. But for all that, perusing Rattelle’s collection is less like reading Stevens’ Ideas of Order than it is like reading Robert Frost—these are poems grounded in the everyday experiences of the everyman, human-scaled and realistic in proportion.

To begin by addressing the most obvious structural choice, the third part, “Hinterland,” is the only part not named after a form of government. It contains a single poem, “All Rising Is by a Winding Stair.” This poem immediately calls to mind not Wallace Stevens, but rather Robert Frost’s “Home Burial,” not only due to the similarity in narrative approach and the shared discussion of the death of a child, but also because the title of Rattelle’s poem seems to echo Frost’s opening line: “He saw her from the bottom of the stairs.” It is set apart from the other poems by its singular placement (the only poem in Part III) and its length (the longest poem in the collection). But it is tied to the collection as a whole by the presence of a growth chart, highlighted in both narration and dialogue, which seems to serve as the fulcrum point not only of the poem itself but of the collection as a whole.

The other three sections are titled with differing ways of imagining governance: meeting house, commonwealth, and republic. There is the sense of progression from the small religious meeting houses of the early colonial era to the more developed commonwealths formed around the time of the American Revolution, and on to the idea of the broader American Republic itself. These forms of governance are all conceived around collective discourse, and their use as titles for the individual parts reflects an important aspect of the selected poems—these are emphatically not heroic lines celebrating the supreme and penetrating expression of individual political will, as in, for example, Marvell’s “An Horatian Ode upon Cromwell’s Return from Ireland.” Rather, Rattelle attempts to depict the interactions and connexions that exist between ordinary people with ordinary concerns and capabilities; not masters of all they survey, but human beings contending with the insoluble complexity of their very real circumstances—and that, surely, is enough to be getting on with.

With 44 poems in Painting over the Growth Chart, including one of relatively longer length, it is necessary to choose a representative selection. Consequently, this review will look at two poems in some considerable detail—taken from the first and last sections—to show Rattelle’s poetical approach and the shared ethos of the poems in this collection.

In our house, there is a growth chart on the back of our cloakroom door. It charts the heights and ages of more than a dozen children who once lived here, none of whom are known to us. Yet when we bought this house, we painted only the front of the door, not the back. It was something that we decided without ever discussing it. Perhaps this is because we recognise that it is not proper—not human—to obliterate the artefacts of human memory, even if we do not ourselves participate directly and specifically in them. Instead, we added our own children to the chart, mingling them with those who have gone before.

Rattelle’s “Painting over the Growth Chart” is in unrhymed, iambic pentameter couplets, but heavily enjambed, thus presenting a sense of rhythmic, temporal order always on the cusp of being undone by the speaker’s stream of thought—a sense which is eventually mirrored in the poem’s content. Rattelle reminds us that “A coat of paint is all it takes and if / it’s not like new, it’s good enough for now”—an easy enough task when the chart and its notches are as difficult to make out as they are in this poem. The speaker opens with, “I had to squint to notice them. The lines / that bicker up the door jamb in the kitchen”—employing not the modern sense of bicker (quarrel, squabble), but instead trading on a variety of its archaic usages: the Middle English ‘attack with repeated strokes,’ the 17th century poetical ‘flash, gleam, quiver, glisten,’ and the 18th century ‘make any repeated noisy action.’

This unusual usage leaps out even as it is paradoxically used to describe something that is hard to see, forcing our attention on the word and on its subject. The notches in the jamb—those repeated strokes—are covered by paint, but still they glisten when the light hits them, flashing as they make a run “up the door jamb” to chart the directional progress of maturity and time. That paint is only ‘good enough for now’: it cannot totally obscure the growth chart’s record of what has been. To remove it entirely, it would have to be sanded away or the wood replaced, so the notches remain as a testament, which the poet can describe.

But another testament remains—that of the children themselves. The speaker imagines what records might survive: “Any sign they ever lived here is blotted out / except, perhaps, in Polaroids stashed / in someone’s attic” alongside the other detritus of time, preserved only because “they couldn’t bring themselves to throw away” these humble but still tangible manifestations of what was once real enough to touch, but is now relegated to intangible memory. In pictures, which are being imagined by the speaker, the people are “all crew cuts and towel-capes on summer break / circa ninety-nine.” This imagination is possible not because the speaker has seen these particular children, but because he can draw upon his own part of the shared human experience in order to conceive an empathetic analogue that rings true.

The speaker’s identification of the self with the other is what provides the impetus for the poem’s climax and conclusion: “But now those kids / are just like me. Beer gut and grays in the drain— / fit for this life and mortgaged into it.” The emotional tension of painting over the growth chart is not located wholly in the obliteration of the tangible relics of the past (as if one could, somehow, touch the past by touching the growth chart). In fact, a great deal of emotive force comes in encountering the growth chart as a sign of one’s own ageing and mortality: the speaker realises that the painting over has happened because of the passage of time, a signifier that adds years and decades to the growth chart and places its once-young subjects alongside himself. Their jaunty towel-capes have given way to mortgages; crew cuts have been replaced by—in a savage rhyme—beer guts.

The observation that in so being changed the former children are at last “fit for this life,” ends the poem on a note of despair, suggesting that this life is no place for the carefree optimism of youth. The speaker may well think so, having been confronted by a reminder of the transient nature of mortality: youth, ageing, death, and the eventual forgetfulness of time, with the visible markers of one’s existence painted over or forgotten in an attic full of jumbled bric-a-brac. But beyond the boundaries of the poem, the poet immortalises the moment and thereby reminds us, as Shakespeare does in his sonnets, that the transcendent power of poetry is to preserve its subject forever: children, Polaroids, and growth charts—paint notwithstanding.

Birds are a motif present throughout Painting over the Growth Chart, with the collection including several poems dedicated to birds as a subject, such as “Birdseed for Very Lucky Birds,” “The Loon,” and “Canada Geese.” Rattelle’s “To a Bird” continues the use of this motif, just as “Painting over the Growth Chart” makes use of an image which is present in another poem and in the title. In another similarity, “To a Bird” is also written in unrhymed iambic pentameter couplets, although not indented, and not so frequently enjambed as in “Painting over the Growth Chart.” The lack of indentation subtly contributes to a smoother sense of inter-line flow—an essential component, given the poem consists of a single sentence, title inclusive.

The poem begins without interruption from its title, thus:

TO A BIRD

who made her nest inside a statue’s palm—

This continuous thought runs to the end of the poem, although the sentence is divided into several independent clauses separated by commas and semicolons. These work continuously to build up a sense of the specificity of the subject, always in relational terms, which moves the reader ever closer to a sense of the bird rather than a bird.

In spite of the fact that the poem is addressed “To a Bird,” its content is descriptive of the bird rather than phrased as an address to it. Like the first section of Ginsberg’s “Howl,” the speaker becomes immersed in describing the experience of his subject, with a transformative result for the content of the poem. For Ginsberg, the speaker’s personal experience (the opening “I saw …”) is subordinated to the described experiences of others, to the degree that the others replace the grammatical subject; but for Rattelle, the speaker cannot even get beyond the title. His address (“To a Bird”) fills everything, not merely delaying the message but replacing or even becoming it, preventing even the opportunity for the speaker-as-subject.

The bird is not alone in the poem, however; all of the descriptions, which would particularise her subjectivity, are relational in nature. It is the bird “who made her nest inside a statue’s palm”; the bird “whose eggs grew cold against the wished-for flesh / and stolen by a boy to throw away”; the bird “who didn’t know she was herself an image / impressed like sealing wax upon a world / of watchers.” As in Steven’s “Anecdote of the Jar,” a facet of the Derridean post-structuralist paradox of subjectivity appears: an individual thing can only be known by its relation to other things. In Rattelle’s poem, as in “Anecdote of the Jar,” these differences (or, perhaps, différances) are the site of alienation. For Stevens, “The Jar was gray and bare. / It did not give of bird or bush, / Like nothing else in Tennessee”; but the bird in Rattelle’s poem is even further alienated. Stevens’ jar is, at least, a dominating signifier—it imposes order and conveys meaning upon the world around it. The bird is only a sign—“an image” in “a world of watchers”—that derives its meaning from the things around it. That it is the subject of the world’s vision seems promising, until the line continues by declaring that the bird is “weary of the post”—exhausted and, like the forest in Stevens’ poem, forced into someone else’s idea of order: “no longer wild.”

Rattelle leaves us there, like the bird, “on the cusp / like static between one station and another.” Our present moment, our world, our very selves are all made up of ‘differences to the other.’ Attending to them and becoming aware of them can be an exhausting prospect for birds and men alike. For it is one thing to acknowledge the infinitely relational aspect of subjectivity—the stuff of empathy and understanding—and quite another to find it agreeable at all times and in all places, in a state of being constantly aware of the contingent nature of being an individual, flickering “like static” between the self and the other. But even if that is so, there is an energy in its poetic evocation, and a movement which bickers across Rattelle’s poems. They leave us, hours or days later, attending to unforgettable images and themes that were once part of the unquestioned sequence of everyday life: the growth charts that peek out from beneath the paint, and the birds that yearn for a human touch from inhuman hands.