When I agreed to review Sohrab Ahmari’s newest book, I wasn’t expecting to learn anything I didn’t know before. I anticipated a straightforward, well-written book that would simply reinforce my conservative presumptions.

Dear reader, I was quite mistaken.

While Ahmari’s new book is certainly well-written, it does not leave readers feeling comfortable. Instead, it challenges readers, conservative and progressive alike, to examine not just their opinions, but their habits and those of their civilization. A century ago, the French scholar Pierre Hadot reminded us that philosophy is a way of life. By this definition, Ahmari’s book is a brilliant invitation to live that life—that is, to live ever more philosophically in our chaotic age.

Before considering the content of the book itself, I ought to say something about its author. But immediately a challenge presents itself: which Ahmari is this? Is this the New York Post journalist? Is it the former Muslim, the one who wrote moving accounts of his conversion? Is it the thoughtful reactionary, signing anti-Reaganite manifestos? Is it the family man caring for his children, or the hothead calling out insufficiently “based” conservatives on Twitter?

Ahmari is a man with many facets and it isn’t always clear from the outside how they all fit together. So, when I first opened The Unbroken Thread, I didn’t quite know which Ahmari I would be getting.

In this book, however, all these disparate Ahmaris come together. The book weaves together lively journalistic storytelling, political philosophy, a deep concern for posterity, and even a few well-placed barbs. All told, the work is a series of genuinely thoughtful reflections on what it is to be human while living within what the author calls “the traditional wisdom of limits.”

The book begins in a rather striking way. The first paragraph is worth quoting in its entirety:

An immigrant isn’t supposed to complain about the society that gave him refuge. That is what I am: an immigrant, a radically assimilated one at that—who nevertheless harbors fundamental doubts about the society that assimilated him.

Ahmari goes on to explain that, growing up in the oppressive nation of Iran, America stood for a kind of freedom and opportunity that he could only dream of. When he moved to America, the young Ahmari took full advantage of this freedom, reveling “in the chance to remake [him]self anew each day.” He was, Ahmari explains, the quintessential modern American autonomous individual:

My moral opinions were as interchangeable as my clothing styles and musical tastes. I could pick up and drop this ideology or that. I could be a high-school “goth,” a college socialist, a law-school neoconservative. I could dabble in drugs and build an identity around my dabbling.

But as he aged, Ahmari realized that this way of life was ultimately unfulfilling. The truest human freedoms, he learned, come not from unleashing the individual from all socially-constructed bonds but from connecting each person with something greater than himself—which requires him to embrace intentional limitation and self-denial.

At this point, Ahmari introduces two figures who are present in the background of nearly every page of the book: St. Maximilian Kolbe and Max, Ahmari’s toddler.

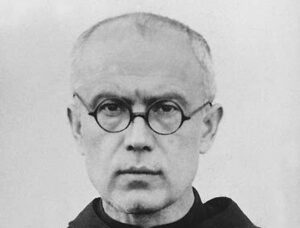

Ahmari’s re-telling of Kolbe’s story is moving, whether or not readers are Christians themselves. St. Maximilian was a Polish Catholic priest who sheltered nearly 2,000 Jews and produced a constant stream of anti-Nazi literature and broadcasts while encouraging repentance and devotion to the Virgin Mary. He was then imprisoned in Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. While there, he spent his days ministering to fellow prisoners and encouraging them to embrace their suffering while rejecting the temptation to hatred.

One day, when a man the Nazis had chosen for death cried out, “My wife! My children!” St. Maximilian stepped forward and offered to die in his place. But the contemporary Western world, Ahmari notes, cannot justify this choice. We today value autonomy and self-expression above everything else. While we may pay lip service to those who sacrifice themselves for others, we do not, in fact, have an account of the good life—certainly not one that includes such sacrifice and suffering.

If Ahmari is right, then what are the consequences of such actions? Why should we care that people value autonomy and freedom so highly?

This is where the author brings Max—his son—into the picture. He offers a powerful description of an imagined future for his son. Whether Max becomes an Ivy League graduate with a high-powered finance job or a basement-dwelling porn and heroin addict, his life will be equally empty if he embraces the vision laid out for him by much of today’s culture. So Ahmari asks himself:

How do I transmit to my son the value of permanent ideals against a culture that will tell him that whatever is newest is also best, that everything is negotiable and subject to contract and consent, that there is no purpose to our common life but to fulfill his desires?

Ahmari wrote The Unbroken Thread as a way of working out how he must raise and form his son. It is both poignant and edifying. For readers, though, the book challenges us to consider how we are constantly being formed and re-formed.

The work owes much of its success to the fact that it is not a polemic but is, instead, “a book of questions.” Individual chapters bear titles like “How Do You Justify Your Life?,” “Does God Need Politics?,” and “What Is Freedom For?,” and each chapter profiles a different historical figure. Implicitly, Ahmari posits tradition as the best way of answering each chapter’s question; but he generally avoids an overly romanticized view of tradition.

As Jaroslav Pelikan put it: “Tradition is the living faith of the dead; traditionalism is the dead faith of the living. Tradition lives in conversation with the past. … Traditionalism supposes all that is needed to solve any problem is to arrive at the supposedly unanimous testimony of this homogenized tradition.”

For Ahmari, tradition is not simply a uniform set of doctrines but, instead, a sort of disposition towards what has been bequeathed to us. Ahmari profiles figures from very different—sometimes radically different—traditions and, in so doing, he challenges readers to figure out how the insights of disparate historical persons can inform our lives today. While he profiles figures likely to be quite familiar to many readers (e.g., C.S. Lewis and St. Thomas Aquinas), he provides fascinating treatments of lesser-known figures (like philosopher Hans Jonas and even the non-Western Confucius).

Additionally, part of the book’s appeal is its structure. Chapters are organized into two broader sections: “The Things of God” and “The Things of Humankind.” It may be difficult for non-religious people to see the appeal of reading a book that explicitly invokes the divine in the title of its first section. Indeed, I initially thought this was a failing of the book. But then I realized that the main structure of the development of Ahmari’s defense of tradition is akin to that of a house: he begins with the foundations: the things of God. From there, he builds up his argument.

Overall, Ahmari wants readers to take the limitations of human nature seriously, and so he begins with the creator of that very nature. While his account will be most convincing to fellow believers, in this book he attempts to discuss religion in ways that the irreligious can engage with.

All this leads me to an important question: why is this book worth the time of committed conservatives—especially when there are already dozens of other new conservative and traditionalist books released each year? We only have so much time—so why am I recommending it?

There are two reasons.

First, this book will challenge your presuppositions and take you out of your ‘comfort zone’—even if you already agree with Ahmari’s views. To be sure, there is a constant temptation for conservatives to think that, since they recognize the importance of retaining what is good from the past, they are somehow protected from the madness of the present. But the biggest challenge for a conservative is deciding precisely what deserves to be conserved.

An excellent example of this kind of deliberation is Ahmari’s discussion of the issue in the book’s fifth chapter, “Does God Respect You?” Here he profiles Howard Thurman, the Protestant theologian and civil rights leader whose grandmother was a freed slave. He touches poignantly on something that many in the West would do well to consider: the fact that Christianity holds within itself the ability to reckon with its own sins, including those surrounding race-based slavery. The same cannot be said for contemporary progressive ideologies like critical race theory.

This leads me to the other reason this book is worth reading: it reminds us how to pass on traditions to others. It’s worth remembering that tradition is not merely something that one is convinced of but, rather, something that one is given. It is handed on and passed down. Conservatives have an obligation to help this transmission—by helping others to love what is deserving of their love.

As St. Augustine—the subject of the sixth chapter—teaches, a man (and, by extension, a community) is defined by his loves. Every decision he makes forms his heart for eternity. Ultimately, his love will be either for God or for the self. Sohrab Ahmari’s The Unbroken Thread points our attention to the various traditions that teach us this fundamental fact. Now it is our task to take custody of them and hand them on.