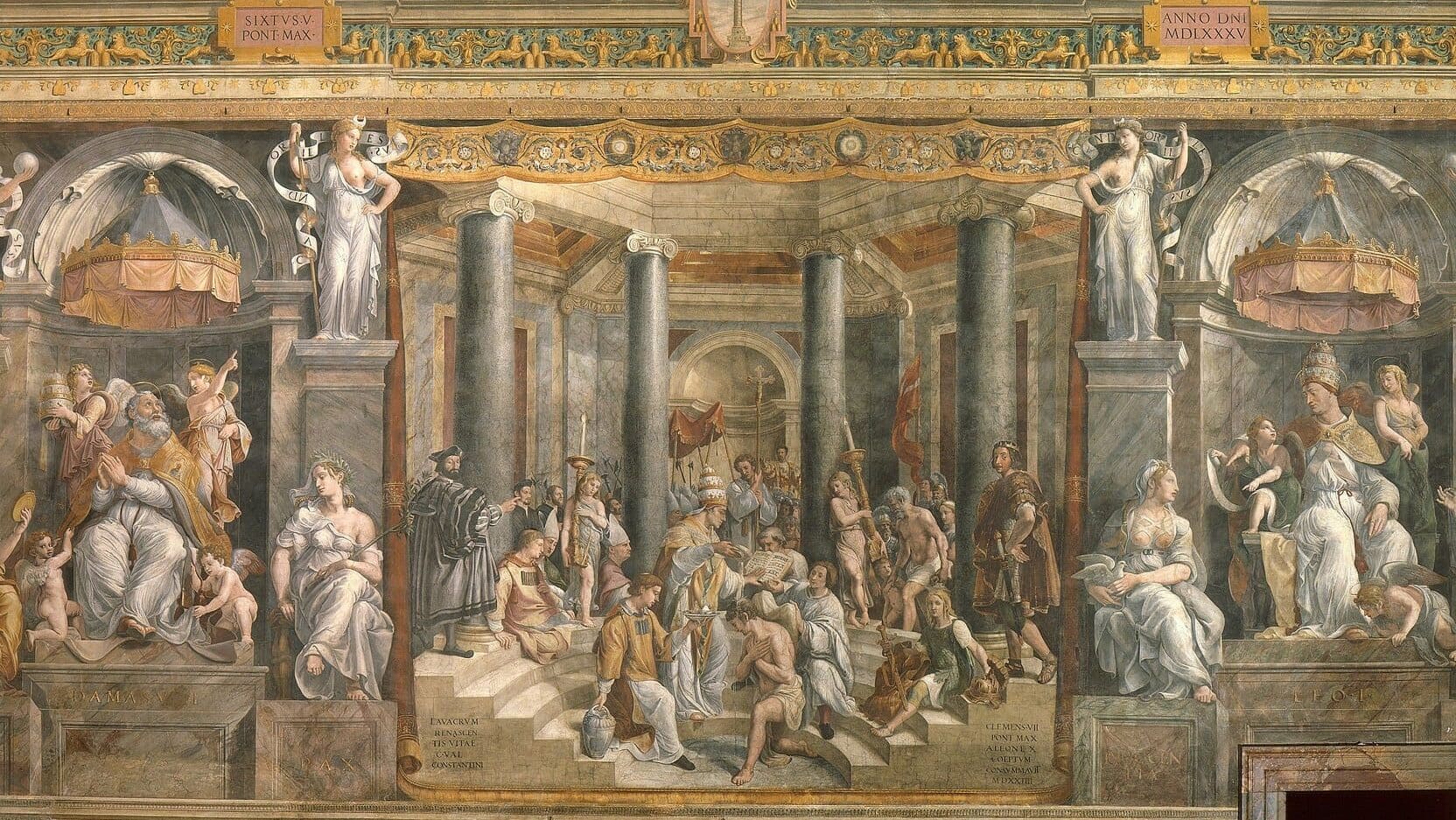

Baptism of Constantine (c. 1520-1524), a fresco painted by Raphael’s assistants, located at the Vatican Museum

In Christ the Emperor, Nathan Israel Smolin’s approach is to read the theology of the 4th century and find ensconced therein the discussions of political structure and governance which seem to be missing from the period’s literature. The task is an important one: the relative absence of such texts has led many scholars of the period—beginning with Edward Gibbon in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire—to conclude that the 4th century was almost entirely given over to an acceptance of despotism and to a concurrent sociopolitical decay.

Smolin is a scholar after my own heart, for my own scholarly modus operandi is to examine works of literature and broader culture in order to extrapolate out from them the contemporary political arguments and positions that the works suggest or assume. For example, Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur can be read as a critique of courtly (as opposed to military) chivalry and governance, which, had it been written in a more explicitly didactic form, might never have survived the author’s imprisonment nor found so great and enduring a readership. Consequently, as a matter of shared approach, I am enthusiastic about Smolin’s “fundamental thesis,” which he sets out in his introduction:

The alleged absence of specifically political theorizing in 4th century texts is in fact the result of the (partial) migration of these discourses from the realm of “secular” politics to that of public Christian theology, wherein questions fundamental to political theory and practice were analyzed, interrogated, and fought over in more far-reaching and consequential ways than ever before.

Although Smolin argues that 4th century theology became the ground for political discussion and theory, he is not primarily arguing for the formation of a specific ”political theology” in the vein of Kantorowicz’s The King’s Two Bodies. For Kantorowicz, late mediæval Christian beliefs served as the foundational principles that shaped the political state, literally embodied in the monarch’s body and the body politic—an idea of development which proceeds from the theological to the political. Smolin argues instead that, in the 4th century, the political migrated to the theological: arguing the nature of Christ’s kingship over creation might become a way to theorise about the nature of a king’s lordship over his realm; more simplistically, it might be advanced as a divine model worthy of emulation by earthly kings; or, it might subsume earthly kingship under it, as a lesser form of the greater kingship sanctified by Christ, with such other shared qualities as might be inferred.

It should not be imagined that such discussions were always purely theoretical, or that they provided necessarily safe theological cover for otherwise thorny political topics. Those involved could (and did) reason out the political consequences of theological positions. Smolin provides carefully researched histories of the participants, which along the way highlight some of the dangers involved in political theorising, even when done through, or by consequence of, Christian theology. For example, the history of Marcellus of Ancyra and his struggle with Eusebius of Caesarea, discussed in the second chapter (“The Theology of Constantine”), demonstrates that what mattered was the actual substance of the arguments and what they implied—not the rhetorical flair or personal loyalties of the discussants.

Marcellus had personally presented his treatise to the Emperor, “hoping perhaps that he would obtain immunity before the Emperor himself because of his encomia of him, and that the bishops slandered by him would be subjected to punishment.” Marcellus, in other words, had thought that any theology could be acceptable to Constantine so long as it was accompanied by proper deference and sufficiently copious praise for the Emperor—and he had been wrong. Constantine had recognized, rightly, the threat to his own Imperial power in the wrong done to Christ’s kingship, and so the Council of Constantinople in 336 had deposed Marcellus from office and Eusebius had published the [Contra Marcellum] to put the last nail in his coffin.

As Smolin goes on to show, Constantine’s attention to the implications of Marcellus’ argument did not make him unique amongst rulers in the 4th century. The latter part of Smolin’s book covers the reign of Constantius II, who was similarly aware of how the theological disputes of the era might come to shape the structure of his governance, from the nature of imperial succession to the extent of his authority. Naturally, not all rulers could have Constantine’s degree of licence, or understanding of the material, when it came to addressing those arguments. Constantius II was fortunate in his education, but less so when it came to his freedom to exercise his authority.

Constantius was in a far weaker position. While like Constantine he seems to have possessed significant intellectual ability, thanks to his thorough education at his father’s direction and his interest in philosophy, theology, and the liberal arts, there was little reason for bishops to take his opinions as reflective of divine inspiration. […] In his dealings with bishops, then, Constantius found himself in a rather unenviable position: reliant on the Church and bishops for legitimacy, expected to intervene in their theological disputes and preside over their episcopal judicial system, but lacking the personal, charismatic authority on which his father had relied. More fundamental still, Constantius lacked Constantine’s basic position as sole ruler of the Empire.

After Constantine’s death, the re-division of the Empire had changed the political equation, with bishops seeking the imperial approval of his sons. Imperial territory was now held by Constantine II, Constans, and Constantius II, imposing a certain degree of competitive jockeying for authority between bishops, who could now appeal to different imperial courts (whilst at the same time those courts might try to make competing use of the bishops). Smolin notes that only after the deaths of Constantine II (in 340) and Constans (in 350), and after total victory in the civil war with Magnentius (in 353), had Constantius “at long last achieved a full succession from his father, replacing him as sole Augustus and ruler of the entire Roman Empire. … Constantius, like Constantine before him, was now ruler of the world.”

With this advent of a new “Cosmic Emperor,” very much in the mould of Constantine, the political nature of contemporary theological arguments, which had been comparatively opaque during the contested 340s, were once again brought into sharp relief. Hence Smolin devotes the second part of his book to an examination of two important anti-Arian theologians of the period: the bishops Lucifer of Cagliari and St. Hilary of Poitiers. Certainly, some academic attention has been given to the theology of the latter figure (a Doctor of the Church); but, in his study of the former, Smolin is breaking almost-new ground. As he notes, the scholarship around Lucifer of Cagliari has been almost entirely negative and has not substantively engaged with his theology, despite the extensive survival of his writings addressed to the Emperor.

Smolin’s use of both Lucifer and Hilary is an inspired choice: although both were vehemently anti-Arian—Lucifer was criticised for being too zealous, and Hilary became known as Malleus Arianorum (“The Hammer of the Arians”)—there were natheless considerable differences in the approach they took in order to defeat Arianism and persuade (or admonish) Constantius. For example, Lucifer took a quite confrontational approach, addressing his arguments directly to Constantius, in the second person, in the manner of a one-on-one exhortation or admonition. As Smolin notes, St. Hilary’s approach was not merely a stylistic whim but rather a choice meant to signal a different purpose for the argument, despite the similarity of the underlying theology—a choice exemplified in St. Hilary’s In Constantium:

The addressee in the early sections of In Constantium is the second-person Fratres, the equal ‘brother bishops’ so prominent in all of Hilary’s writings, and for the bulk of his work, Constantius is described in the third person, his wicked actions narrated for the benefit of a clearly episcopal audience. … Lucifer’s works, which never stray from a tight second-person address to the Emperor, were written with Constantius as at least one intended audience, with the genuine goal of admonishing him and converting him from error to truth. Hilary’s invective against the Emperor, in contrast, has as its goal not the conversion or correction of the Emperor but, like practically all of Hilary’s works, the persuasion and unification of his fellow bishops.

Here, Smolin shows, it is not always theological principle per se, but sometimes the use of the venue of theology as a ground for argumentation, which becomes the means through which the political is addressed. Moreover, there are underlying implications—Lucifer’s direct confrontation of the Emperor implies a hierarchy of roles in which the bishop is above Constantius and thus able to correct him—at least in matters of Christian doctrine (but possibly more). Conversely, St. Hilary’s speech, addressed to his brother bishops, does not rest upon such an assumption—although it does not preclude the possibility of ecclesial supremacy, either.

Smolin finishes his work with several helpful additions: an epilogue addresses the history of the emperors after Constantius, up to and including the Theodosian Settlement, when the bishops once again propped up the shaky Imperial polity. This section, although brief, helps to round out the historical narrative of the period and give a sense of chronological finality to Smolin’s thesis. It is followed by two thorough appendices. The first, and likely the most important for the vast majority of readers, is a ‘timeline’ of episcopal councils which occurred in the periods under study in the text: under Constantine, under Constantius II, and after Constantius II. This appendix is no mere list of councils and dates; Smolin provides details of the most significant acts by each council, helping to put into context the events of the text. On its own, it is useful and concise, such that it warrants especial praise. The second appendix contains several pages on the dating of key texts, which will be of use to experts in the field. A solid index rounds out the presentation, including all of the major personages referenced in the text, along with some of the major topics as well.

As might be expected from such an erudite work, published in the Oxford Studies of Late Antiquity series, the book does have a certain scholarly style. However, it never verges into obscurantism or opaqueness, and it is refreshingly free of the ponderous and repetitious verbiage that too often covers for a shallow knowledge of the material. When reading Smolin, the sense of his absolute command of the scholarship is constantly present, supported by the author’s exceptional facility for explaining the complex relationship of 4th century theology and politics. To make such a topic understandable would have been accomplishment enough; to have made it both readable and even relevant is worthy of high praise, indeed.