It is a dangerous time for those who express love of their own. Public expressions of devotion to one’s family, nation, or Church quickly occasion accusations of religious extremism, racism, xenophobia, or transphobia. This instinct to pathologize the love of these natural objects of pietas was usefully characterized by Sir Roger Scruton as oikophobia, the tendency within much of Western elite culture, fostered by much of academia, to promote an anti-culture based on the repudiation of what has traditionally been revered as holy. Oikophobic discourse and practice typically serve the power of the utilitarian bureaucratic state, abstracted and deracinated as it is from local communities and their common goods.

To paraphrase G.K. Chesterton, another option besides arguing from within our own present discontents is to assume a position wholly outside of them and see what we can discover there. A recently released Bollywood action film, Pathaan (2023), presents an interesting portrayal of Indian nationalism, which, while perhaps initially appealing to a Western audience tired of reflex oikophobia, should prompt us to question whether devotion to the nation, lacking the Christian emphasis on the family and the dignity of the human person, might not devolve into something quite inhuman.

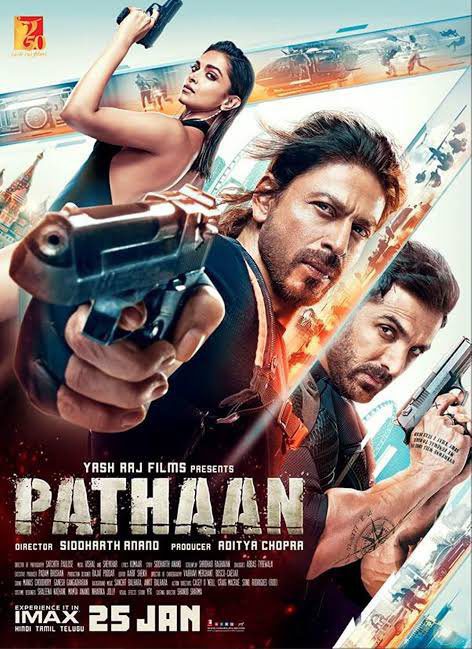

Bollywood films in general present an interesting contrast to American cinema. I discovered the strange territory of Hindi films—typically longer than American films, clocking in usually at 2.5 to 3 hours, replete with dance numbers and comedic digressions from the central plots concerning marriage and family—about a decade ago, when my mother, herself an immigrant to the United States from India, brought such a film home one day. I quickly became entranced. Made for a general audience, Bollywood movies tend to avoid the sexual obscenity common in Hollywood movies, and typically contain a variety of elements that appeal to adults and children alike. As such, films like Kuch Kuch Hota Hai tend to have an appeal like that of a Shakespearean comedy, addressing multiple audiences at once. So when I took a trip to the theater to see the incredibly popular Pathaan (its trailer can be viewed here), I was expecting just a fun action film, but found myself confronting a thought-provoking tale of duty and patriotism.

The plot of the movie is fodder for a delightfully thumotic patriotism, in a similar way to many American action movies from not long ago. When India is threatened by a multinational terrorist group, Outfit X, its external intelligence agency, Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), recalls to the country’s aid an exiled super-soldier, Pathaan, who partners with Rubina “Rubai” Mohsin, a former love interest and an agent of the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), in order to thwart the deployment of a bioweapon against a major Indian city. While the pro-Indian sentiment of the movie refreshingly contrasts with the anti-American fare on offer in the United States these days, the inner workings of the plot and the character of its hero showcase the problems of Indian nationalism, as the movie portrays it—whether that reflects the reality of Narendra Modi’s BJP and its Hindu nationalism, I leave to others to decide.

The film centers around the conflict between Pathaan and Jim, the leader of Outfit X, compellingly played by nationalist actor John Abraham. At its opening, set in 2019, we witness the reaction of the Pakistani general Qadir to the news that India has revoked Article 370 of its Constitution. Article 370 had granted special status to Jammu and Kashmir, the latter of which has been claimed by Pakistan due in part to its majority Muslim population. Qadir declares that the revocation of Article 370 is an act of war, but that fighting such a war should be undertaken not by men of god—it is time, he claims, to instead partner with the devil. He immediately calls Jim, telling him that he wants India brought to its knees within the three years that Qadir’s doctor has told him he has left to live, due to his battle with cancer. Meanwhile, injured RAW agent Pathaan decides with his supervisor, Nandini, to open a new unit designed to recruit other injured agents who still desire to serve their country. They discover an apparent threat to India’s president at a scientific conference in Dubai. The apparent threat posed by Outfit X is just that—merely apparent—and Jim manages to capture a prominent Indian scientist after a fight with Pathaan forces him to reveal his identity.

Jim’s origin story as a villain presents the movie’s first implicit critique of a certain kind of nationalism in the movie. As RAW joint secretary Colonel Luthra reveals upon Pathaan’s return to India, Jim was a former RAW agent, one of the agency’s best, who had single-handedly taken on a ship of Somali pirates. Despite his valor, however, when Jim and his pregnant wife were captured by the same pirates out of vengeance, India stuck to a bureaucratic rule: “we don’t negotiate with terrorists.” This refusal to negotiate resulted in the death of Jim’s wife and unborn child, and even Pathaan criticizes the colonel’s unwillingness to act on behalf of a good soldier who had been loyal to his nation. Such a failure seems unfortunately typical within a bureaucratic apparatus which encourages citizens to simply follow the rules rather than exercise their own hard-won virtue of prudence.

This is not to say that an appropriate deference should not be shown to those in authority, but that discerning precisely what is due requires human beings to act reasonably, rather than simply trusting the bureaucratic system to discern right from wrong. Although bureaucracies might be instituted to protect certain common goods, they too often end by seeking to protect their own existence rather than the good of the communities which support them. Thus within a bureaucratic apparatus there tends to be an appeal to justify official actions by appeals to arbitrarily set ‘best practices’ rather than a care for the particular set of circumstances, namely, the precise location of the exercise of justice and prudence.

Thus, while rejecting his actions, Pathaan is sympathetic towards Jim’s position. Jim’s deracinated cosmopolitanism—in one notable scene he claims to belong to no country, to owe allegiance to nothing higher than himself—comes from a deep sense of having been betrayed by his nation. In his case, India failed to act for his good by repaying his loyal service, but took comfort in simply playing by the book. While Pathaan might relate to his country as “Bharat Mata” (Mother India), Jim was a lover of his country who, having been spurned, turned his back on her. When Jim’s final plan is revealed—the use of a newly developed quick-acting smallpox variant on an Indian city via a descending passenger aircraft—Luthra’s response reveals that he has not learned from his mistake of failing to help Jim. As Pathaan battles Jim in the film’s final fight scene, the colonel deploys a missile to destroy the plane full of innocent passengers, including women and children, to avert a greater potential loss of life. Although Pathaan manages to stop the timer on the bioweapon, prompting Luthra to abort the missile, the willingness of the intelligence secretary to sacrifice the lives of innocent civilians to a soulless and utilitarian calculation of costs and benefits presents a powerful challenge to the legitimacy of the national enterprise as a whole.

The utilitarian bureaucratic approach to national security, as presented by Luthra, contradicts the priority of families and human dignity that nations ought to protect. The nation as a political form uniquely allows for the flourishing of persons and families in the contemporary world, but must not succumb to the danger of bureaucratization, by which the perpetuation of the nation as such at any cost becomes the ordinary purpose of the regime—ordinary soldiers and citizens be damned. The prevention of the story’s main action from becoming a national tragedy depends largely on the character of Pathaan and his care for human dignity and particular communities. His formation of the Joint Operations and Covert Research (JOCR) unit was motivated not only by his love of nation but also by the desire to heal wounded soldiers, conceived metaphorically as the Japanese art of kintsugi, in which broken ceramics are re-formed with veins of gold and made even more beautiful despite their fragmentation. We later discover that his code-name represents a similar kind of care; he received it as a gift from Afghani villagers when, as a soldier fighting Islamic terrorism, he saved the lives of that village’s innocents, sacrificing his mission’s objectives and potentially his life to do so.

When at the end of his final, epic fight scene with Jim, he adapts a famous saying of John F. Kennedy’s, “A soldier does not ask what his country can do for him, he asks what he can do for his country,” the audience senses that Pathaan speaks not of the nation as an abstraction, but rather as a real community, protecting smaller communities and the human beings who were born and raised with a particular language and way of life.

The audience’s sympathies with Pathaan arise not primarily because he made a different choice than Jim upon being exiled after his first mission’s failure, but because he displays a love of nation founded on a love of particular human beings and communities, and an understanding that the nation ought to serve rather than dominate that which is smaller than itself. Thus, in an intriguing twist, the film presents a challenge to any nationalism that supports a bureaucratic and utilitarian approach to preserving the nation at all costs, but suggests that the security of families and the dignity of persons present a compelling reason to preserve a world of nations against multinational bids for cultural and political hegemony. But in order to exist, nations will need heroes like Pathaan, living men and women who care about their fellow human beings enough to risk all for them. Such care can only be built on an expansive love of home.