When people ask me to recommend books that explain our strange times, a few immediately come to mind. To understand the current gender insanity, Abigal Shrier’s Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters; on the abortion debate, Tearing Us Apart: How Abortion Harms Everything and Solves Nothing by Alexandra DeSanctis and Ryan T. Anderson; and to grasp the ways in which the sexual revolution has transformed our politics at every level, Mary Eberstadt’s Primal Screams: How the Sexual Revolution Created Identity Politics. There are at least a dozen others on my list as well. Again, we live in a strange new world, and it helps to have maps.

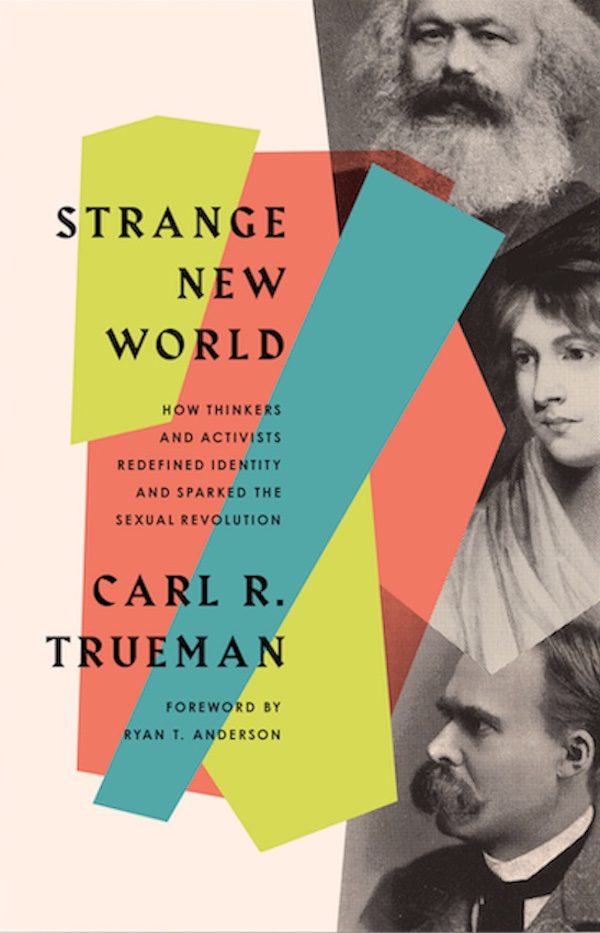

But if I had to limit my recommendation to a single book that explains what has happened to Western civilization from a historical and intellectual point of view, I would urge you to read Carl Trueman’s Strange New World: How Thinkers and Activists Redefined Identity and Sparked the Sexual Revolution, published earlier this year by Crossway.

Trueman is a professor and historian who teaches at Grove City College in Pennsylvania, where one of his areas of scholarly interest is the “rise and impact of modern notions of selfhood on contemporary culture.” That research resulted in the publication, two years ago, of his 400-page The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism, and the Road to Sexual Revolution. It is a dense, powerful read, and it put Trueman on the map not only as a historian of ideas, but as the man capable of explaining our current moment. In a world gone mad, Trueman has answers.

Strange New World is a condensed version of his 2020 offering for a broader, less philosophically inclined audience. It is eminently accessible and should be widely read by anyone who wishes to grasp our historical moment. Not many historians become famous, but Trueman’s work is having something of a moment. The Daily Wire’s Matt Walsh, who interviewed Trueman for his documentary What is a Woman?, referred to him recently as one of the most important public thinkers alive. I’ve seen Trueman’s work cited all over the place recently, and he’s been making the long-form podcast rounds; most recently appearing on the British show Triggernometry.

In the space of 208 pages, Trueman explains how sex, gender, and how one ‘presents’ became an expression of the inner self—of ‘my truth’—and how social recognition of that public-facing inner self became a fundamentally political project. As Ryan T. Anderson noted in his foreword, Trueman has laid out, both historically and philosophically, “how the person became the self, the self became sexualized, and sex became politicized.” With the personal becoming political in a literal sense, every public space has become a battleground, with any refusal to recognize someone’s subjective truth being seen as akin to violence. The cultural implications of this are obvious and everywhere.

We have, Trueman writes, been heading in this direction for a long time—but a key utility of his work is that he explains our historical trajectory to the many people who are bewildered by what has unfolded in the past decade or two. I’m 34, and I remember when the transgender movement exploded onto the scene like an alien out of the rainbow chest. Similarly, many older folks feel ‘gas-lit,’ or wonder if the arc of the moral universe does really bend so dramatically away from the ways in which we and all our ancestors lived within recent memory.

So how did we get here? As Trueman explains it, three intertwining concepts and their origins must be understood to grasp our current culture: expressive individualism, the sexual revolution, and our social imaginary.

Robert Bellah defined expressive individualism as holding “that each person as a unique core of feeling and intuition that should unfold or be expressed if individuality is to be realized.” This, of course, runs directly counter to the traditional Christian view that the human heart is “desperately wicked” and “deceitful” (in the words of the King James), and that suppression of many desires and impulses is essential not only for a Christian life but for a fulfilled one. In our current culture, sex and gender are how individuals express themselves. Thus, someone does not experience same-sex attraction—they are gay. As Trueman writes: “If a person is in some deep sense the sexual desires they experience, then how society treats those desires is an extremely important political question. Further, the political struggle itself shifts into the psychological realm: oppression is now not simply something that involves being deprived of material prosperity or physical freedom.”

To summarize, Trueman observes: “It is my conviction that the dramatic changes and flux we witness and experience in society today are related to the rise to cultural normativity of the expressive individual self, particularly as expressed through the idioms of the sexual revolution. And the fact that the reasons for this are so deeply embedded in all aspects of our culture means that we all are, to some extent, complicit in what we see happening around us. To put it bluntly, we all share more or less the same social imaginary.”

Philosopher Charles Taylor, author of A Secular Age, defined a social imaginary as how people “imagine” or perceive their surroundings, shaped by images, stories, legends; it is everything that makes up “that common understanding which makes possible common practices and a widely shared sense of legitimacy.” Our social imaginary today is shaped not only by a post-Christian culture, but by an increasingly anti-Christian one. Our culture’s storytelling institutions—Hollywood, the small screen, much of our literature—have been entirely captured by the sexual revolutionaries. Even children’s entertainment sells the revolution, from lesbian polar bears on the TV show Peppa Pig, to same-sex families on Disney blockbusters, to beloved animated characters coming out as queer.

So how do Christians build communities, raise their children, and be a salt and light in a culture with values—and stories—that are fundamentally at odds with Christianity? Trueman sees historical parallels to another era, and a distinct advantage of our own. “There are obviously fundamental differences between the church in the second century and the church in America—we are deChristianizing,” he writes. “In our context, Christianity has been known and is being repudiated. In the second century it was an unknown quantity. But what makes the church powerful as a force in the first and second centuries is its community aspect. Not just families, but the power of the Christian community as a community.”

“Push back against the age as hard as it pushes against you,” Flannery O’Connor once wrote. To respond to the times we live in, we must first understand them. Trueman’s Strange New World is an excellent place to start.