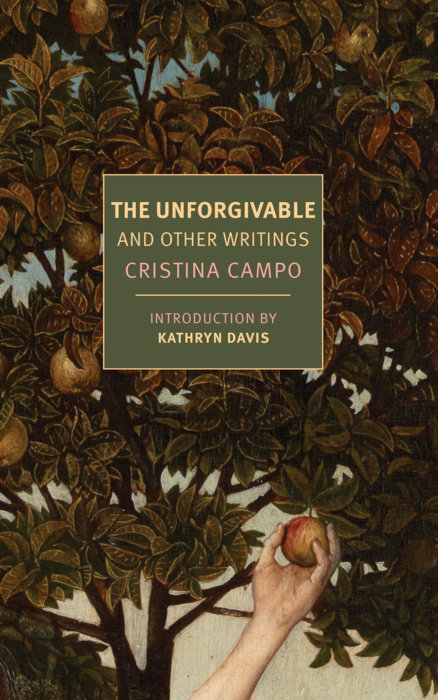

“High Traditional Latin (Tridentine) Mass in St. John of Nepomuk Catholic church in Prostějov, Czech Republic, 16th April 2023” by Novis-M, CC BY-SA 4.0. Cristina Campo had a great love of the beauty of the Old Mass.

If Cristina Campo is remembered at all outside her native Italy, it is usually because of her involvement with Una Voce, an organisation founded in 1964 to foster the cultural heritage of the Latin rite of the Catholic Church. But there is another side to Campo, who was also a distinguished poet and essayist. Neglected by the mainstream and untranslated into English until now, her work has languished in European literature’s dusty bottom drawer. Part of the reason for this neglect was that she published only two short books of prose in her lifetime: “I have written little,” she once said, “and would like to have written less.” Another reason is that she died young. Born in Bologna in 1923, Campo—or, to use her full name, Vittoria Maria Angelica Marcella Cristina Guerrini—died in Rome a mere 53 years later. We should, therefore, be grateful to NYRB for publishing this wonderful collection of her prose. It has certainly been worth the wait.

Underlying much of Campo’s work is a keen sense of loss. As she wrote in what is perhaps her greatest essay, “The Flute and the Carpet”:

What does any examination of man’s condition come down to today if not a list—stoical or terrified though the list-maker may be—of his losses? From silence to oxygen, from time to mental equilibrium, from water to modesty, from culture to the kingdom of heaven. And there really isn’t much to offset the horrifying catalogue. The whole picture seems to be that of a civilization of loss.

Writing primarily in the 1960s and 1970s, Campo was, of course, responding to the destruction she saw all around her, but the root causes of that destruction stretched back long before the horrors of the 20th century:

The Renaissance, the Reformation, the incessant necessity of theological disputes, above all the Enlightenment: all of these trials were promptly overcome by doctrine, but each time it seemed to tear away another strip of the radiant corporeality, the vivid skin of the old Christian life.

So what was to be done? What could a writer in the 20th century still do? Having outlined this horrifying catalogue of losses, Campo boldly announces the possibility of “a civilization of survival,” in which might survive “some islander of the mind still capable of drawing up maps of the sunken continents.” This was how Campo saw herself: as a cartographer of sunken continents.

First among these continents were the writings of the Desert Fathers upon which, Campo argued, “the whole mystical Church of the East” had been built. It was precisely here, in the “radical silence that only their rare sayings would have furrowed,” that Campo discovered the foundations of her broken civilization, the beginnings of a tradition that stretched out through Athanasius, Chrysostom, Basil, Cassian, Benedict, the Philokalia, The Way of a Pilgrim, Lorenzo Scupoli, John of the Cross, and Elizabeth of the Trinity. Here too, Campo discovered a model for her own writing, for the Desert Fathers said little and would have liked to have said less.

Campo may have been a cartographer of sunken continents but she also mapped an archipelago that had somehow escaped the apparently universal Atlantean destruction. Her essays on the work of Borges, Simone Weil, Marianne Moore, William Carlos Williams, and John Donne are all miniature masterpieces, as are her reflections on “those little gospels called fairy tales.”

Understanding Campo’s attitudes towards fairy tales is the key to understanding all her work, for she saw them all round her, not just in fairy tale collections but also in the Book of Tobit—“the fairy tales of all fairy tales, the journey of all journeys”—and “the sayings and deeds of the Fathers were at all times collected with extreme devotion, for they were almost always very hard, uncrackable nuts, to be carried around for life and crushed between the teeth, as in fairy tales, in the moment of gravest danger.”

These fairy tales are “a first initiation, if not to the meaning, at least to the power of symbols,” providing an essential education for adults and children alike:

It is worth noting that a writer who attempts a fairy tale unfailingly produces his best prose, becoming a writer even if he has never been one before: almost as if language, when it comes into contact with symbols so universal and particular, so sublime and palpable, cannot help but distill its purest flavor. So that a classic book of fairy tales opens not only the atlas of life for a child but also the atlas of language.

Above all else, though, Campo believes that fairy tales, like attention, give us access to reality. Her arguments, though not dissimilar to those of Chesterton and Tolkien, have a distinctly Franco-Italian lilt thanks to the mediation of Simone Weil: “If attention is a patient, fervent, fearless acceptance of reality,” it is possible to understand Beauty and the Beast, “like any perfect fairy tale,” as being “about the loving re-education of a soul—an attention—which is elevated from sight to perception.” If attention “is the only path to the unsayable, the only path to mystery,” it is most purely expressed in the fairy tale, for attention, like fairy tales, “is firmly anchored in the real, and only through allusions hidden in reality is that mystery manifested.”

Eschewing the Romantic idolisation of the imagination, Campo argues that fairy tales are the surest guides to reality, the paths on which we travel to the real, the source of spiritual truths bound up in earthy realism: they are “a quest for the kingdom of heaven, the pursuit of an unknown and inexplicable vision, often only of an arcane word, for which the hero abruptly deserts his beloved homeland and all good things in order to become a pilgrim and a beggar, a holy fool with a heart of fire, whom the whole world will mock and that ‘the world behind the real world’ will help and guide with marvelous signs and wonders.”

One of Campo’s great strengths as a cartographer of sunken continents was that she rarely allows herself to be drawn into controversies in her writing. Despite the occasional wry comment (“It is obvious that, when referring—here or elsewhere—to Catholic things, I am always referring to the period from year 1 to 1960 AD,” she writes in one endnote), she tends to concentrate on her cartography of sunken continents, her mapping of lost beauty. Her discussion of the liturgy is, therefore, both surprisingly limited, given what we know of her participation in Una Voce, and also incredibly powerful.

It was in her writing about the traditional liturgy that Campo’s poetic gifts are most apparent. In one of her most important essays, “Supernatural Senses,” she writes about “the delicate Latin Host made of white and transparent flower, the pure veil of something else entirely, round like the circle of infinity, the center and circumference of the cosmos, offered, in the shafts of sunlight, to the eyes before the mouth.” It was this awareness of divine beauty which leads her to lament the corruption of the liturgy she saw all around her:

the bread, the loaf that is supposed to be broken and distributed at random, however and wherever, like an ordinary meal, has, with terrible retributive justice, gradually lapsed into being a mere sign and from being a mere sign to being a mere abstraction—and all the while, people more and more naively believed they were sinking their teeth into it.

However, rather than focus on the triviality of such liturgical experimentalism, she prefers to write about the splendours of the traditional rite:

the flames, the incense, the tragic vestments, the majesty of the gestures and faces, the rubato of the songs, the steps, the words, the silences—the whole vivid, luminous, rhythmic symbolic cosmos that never stops pointing, alluding, referring to a celestial double whose mere shadow on earth it is.

The loss of beauty she sees in literature is not an isolated phenomenon but another example of the neglect into which symbols have fallen in the modern world: “The inexpiable crucifixion of beauty, the universal martyrdom of the symbol—which announced both the presence and the elusiveness of the tremendous—has robbed us of our ability to perceive what is above all unique to the tremendous: the divine realism that surpasses any created reality.” A return to beauty is, therefore, a return to reality. Not for her the “baleful homeopathy that advises treating a world insanely sick with squalor, anonymity, profanity, and license with squalor, anonymity, profanity, and license.” She longed for a restoration of beauty, for a restoration of the traditional Mass.

The liturgy, she writes, “now shines like a cupped candle on only the most inaccessible rocks—Mount Athos, a few Benedictine peaks—or in the most miniscule pigeonholes, lost and forgotten in the metropolis.” In the 1970s, it seemed as though the Old Mass had gone for good, in the West at least, which left her in a bind. She could continue to campaign with Una Voce, but she also realised that,

amid the consternating silence of the religious world, it will once again be up to the person who dwells in symbols and images to cry out without relent, so that the power of the real goes back to imprisoning his heavens and the absolute to transmuting his earth: in that new nature unknown to us, made with divine saliva, which exudes the milk and honey of sweet reasonableness.

Questions of style are, therefore, of fundamental importance when assessing Campo’s work. The derogation of beauty is not, she argues, simply an aesthetic mistake: it creates a deep wound in civilization, a wound that could not readily be healed. When society ignores, dismisses, or disparages beauty, it cuts itself off from reality itself. The writer’s task, then, is to restore what has been lost, to point to what has been forgotten, to recreate in miniature what was once universal.

Style matters, which, in turn, means that translation matters too—though it must accompany an inevitable loss, a fact that Alex Andriesse, the translator of this volume, acknowledges when he explains that “Campo’s knowledge of our tongue, among others, seems to have made her especially keen on Italian’s nontransferable resources: the pronouns and article implicit, the subjects deferred, the inversions abundant.” The wonder is that the translation works at all, and yet it does. Something of Campo’s wonderful sprezzatura remains.

Sprezzatura: in this word, first used in Castiglione’s The Book of the Courtier, Campo encapsulates her inspiration and her goal. It is a word whose apparent simplicity covers great complexity. Sprezzatura isn’t simply “elegance” or “nonchalance,” Campo argues, but “a whole moral attitude,” a “moral rhythm … the music of an interior grace.” It is, above all else, “an alert and amiable imperviousness to the violence and baseness of others, an impassive acceptance—which to unperceiving eyes may look like callousness—of unchangeable situations that it tranquilly ‘decrees nonexistent” (and in so doing ineffably modifies).”

It is sprezzatura that Campo values in the work of Borges and “holy sprezzatura” that she finds in the Gospels: “the generosity of spirit is at its root, and a joyful way of being in the world.” It was because she was dedicated to the pursuit of sprezzatura in her life, as well as in her writing, that she was able to find a joyful way of being in the world, and that she was able to stand back—though never aloof—from the controversies of her day to produce the numinous prose we are now so fortunate to have in an English translation.