Ten years since he was murdered in a provoked car wreck that continues to be masqueraded as accidental, the life of Oswaldo Payá Sardiñas (1952-2012) appears to readers of David Hoffman’s new biography like a 60-year-long race against Fidel Castro. What the two men were racing toward came into sharper focus upon Castro’s natural death in 2016. By removing every obstacle in his path, the socialist strongman lived to perpetuate into the 21st century the tyranny dressed up as egalitarian utopia he had launched in a revolution the year before Payá’s birth. By envisioning, instead, a Cuba where the people freely ruled themselves, the Christian dissident had become Castro’s main obstacle by the early ‘10s. And so it came to pass that, in 2012, in the sweltering mid-July heat on a deserted highway near Bayamo in Cuba’s east, the world’s oldest dictatorship got a new lease on life. Despite Payá’s steely resolve to outlive his regime, Fidel won the race to Cuba’s future on that day.

The Castro regime likes to portray dissidents as greedy, self-seeking, decadent politicians on America’s dole, but such questioning of Payá’s motives somehow never quite stuck. Father Jaime Ortega—whose official dealings with Castro through the Church’s diocese in Havana made him look like an appeaser by contrast to Oswaldo’s more contrarian streak— described Payá as “a man of faith embarked on a political mission.” This does not mean that Payá’s lifelong struggle to bring about democracy in Cuba turned his attention away from religion. Instead, faith was the wellspring from which his politics sprang all along. Asked by Mexican-American anchorman Jorge Ramos in a 2003 interview why he risked imprisonment and murder by returning to Cuba, Payá intoned: “I will return in order to live or die in God’s hands.” Payá was a textbook Christian democrat—in that order. Unlike Europe’s exponents of that doctrine, his conviction was truer, doggedly lived out under the grinding test of totalitarianism.

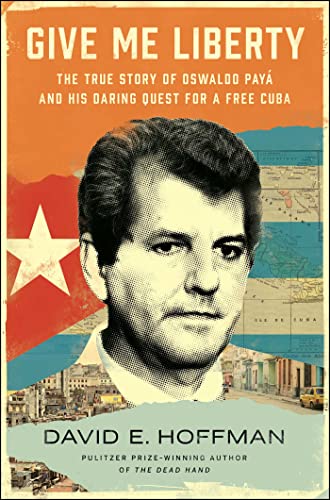

In Hoffman’s account, the Church worked as a pressure valve of sorts for Payá’s freewheeling mind. Breathing an air of relative liberty within it, Payá was able to conjure up a different future for his compatriots, yet the regime’s ideological corset would come to haunt him at times. Raised into the Catholic bourgeoisie, Payá witnessed the Church’s marginalization throughout Castro’s initial decades in power. He took up a couple of key posts within the laity and began distributing several newsletters modeled after Eastern Europe’s samizdat, aiming to instill such plain yet counterrevolutionary concepts as the inherent worth of every human being. “The faith,” writes Hoffman in Give Me Liberty, “was a steady keel on which he centered his life,” and it infused Payá with the “conviction that freedom is an attribute of every person, endowed by God, not the state.” Yet in the late ‘90s, Ortega began censoring his speeches, and Payá turned to other conduits for change.

Given the sheer depravity of the regime he bore witness to, that Payá would prove able to think up such a future in the first place was no foregone conclusion. Payá was 13 when he witnessed his father’s newspaper business ransacked by the secret police. Later, he was the lone pupil in his class to refuse joining the Pioneers, the regime’s youth group. He spent three years in labor camps to discharge himself from military service. Once he launched the Varela project—his lifelong, twice-successful attempt, as allowed by Cuba’s 1976 Constitution, to gather 10,000 signatures in support of basic freedoms—Payá became a target of incessant browbeating and ostracism. Yet he never once relented, always trusting that meaningful change could be achieved non-violently by working fearlessly and tirelessly within the system. Was Payá a tad rash or outright naïve? Likely both. The most enduring element of Payá’s legacy is doubtless his dogged resolve to stand athwart tyranny against all odds.

Another element of his legacy is how large Payá’s figure loomed both inside and outside Cuba, in a way only attained since his death by the ‘Patria y vida’ cultural zeitgeist that rocked the island in 2021. Most of Payá’s entourage had decamped to Miami by the time he reached adulthood, and most still see exile as the sole way to avoid collaboration with the Castro regime. Inversely, those trapped within Cuba can be forgiven for seeing Miami as an extension of America’s undue influence on Cuban affairs. Payá, for his part, was enough of a thorn on Castro’s side to command the respect of exiles yet grounded enough in the realities of modern-day Cuba to eschew the ‘gusano’ label. “If anyone is going to leave Cuba,” Payá once said, “that must be Fidel.” Throughout his life, Payá remained convinced that a solution could only come from within Cuba, and that to attain it, the two camps had to work in tandem. He likened them to two halves of a heart, lamenting that when failing to cooperate, “both halves suffer.”

The tenor of Payá ’s message to fellow Cubans rings more ominously when set against the cruelty of his assassins. That Payá died in an accident is a ruse the regime blackmailed pro-democracy activist Ángel Carromero into confessing, one he quickly dispelled when set free. Their car was rammed off the curb and into a tree by a truck manned by the secret police under direct orders from Castro. One ex-colonel even claims to have seen Payá walk off alive, making his murder even more cold-blooded. The grace and forgiveness that Payá centered his life on preaching—“let there be no hate in our hearts, but instead a thirst for justice and a desire for liberation”—may strike as the kind of turn-the-other-cheek innocence that rarely defeats tyrants. Perhaps Payá was always meant to be a martyr, not a liberator. May his memory, in that case, inspire Cuba’s youth to lose fear and rise up. As Payá said upon receiving the Sakharov Prize in 2002: “the night will not be eternal.”