I was late for Ash Wednesday Mass last year, hastening my six-months-pregnant belly and swollen feet through the early morning frost on the University of Notre Dame’s campus. We opened the heavy doors of the basilica to find the pews overflowing, mostly with undergraduate students. I approached a pew near the back of the church and its occupants pushed even closer together to make room for me, my husband, and our unborn child. On an ordinary weekday, I would have my pick of a place to sit, even if I arrived late to Mass. And yet, for this somber liturgical reminder that we come from dust and to dust we will return, students were eager to wake up earlier than usual to celebrate the Eucharist and receive ashes before attending class.

I had known, of course, that Ash Wednesday is one of the most popular days for church attendance (on par with Christmas and Easter), exercising a magnetic pull on even those who are otherwise disinclined to religious worship. I had known this intellectually, that is—but having been born into a family of practicing Catholics, I find that it takes me by surprise every year. Even as a child, I could understand why a person would be drawn to Midnight Mass or to a sunrise service on Easter morning. I looked forward all year to these joyous occasions: to the beauty of the liturgical music, to the flowers decorating the church, to the fulfilled anticipation after the long weeks of Advent and Lent. But Ash Wednesday? Why would an irregular worshiper want to show up for fasting, sobriety, and reminders of our mortality?

Matthew Walther offered a beautiful reflection on this phenomenon for The Lamp, identifying two reasons why non-practicing Christians flock to Mass at the beginning of the Lenten season. First and foremost, he suggests that “those who are separated formally or otherwise from the visible body of believers repent of their sins and wish to declare this, even though, indeed perhaps especially because they have yet to arrive at a firm purpose of amendment.” Additionally, most of us live in a society devoid of public expressions of religious conviction. In the Church today, ashes are normally administered to the faithful in the form of a cross smeared visibly on the forehead. I remember how emboldened I felt, as a young professional in Washington, DC, when I saw this mark on other commuters on Ash Wednesday. This wasn’t virtue-signaling, but a bolstering of my individual faith through a visible reminder of the Church as a communion of persons, united in Christ—not just in the glory of His resurrection but also in the suffering of His cross. While the Church reserves the reception of the sacrament of the Eucharist to baptized members in good standing, the ashes blessed at the opening of the Lenten season—which are a sacramental—are available even to those with a more tenuous relationship to faith. These ashes indicate a tangible commitment to repentance that finds no analog in the secular realm.

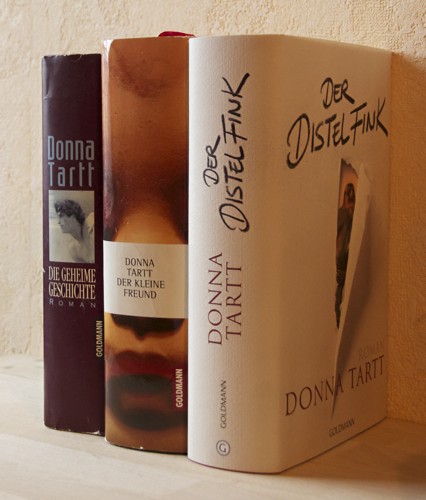

Ash Wednesday is, in my opinion, the linchpin for understanding the debut novel of American writer Donna Tartt. In a recent piece for the LA Review of Books, Richard Joseph expressed surprise at the fact that Tartt has not garnered the same kind of literary standing as many of her contemporaries. I have wondered the same, particularly with regard to her standing in the Catholic literary movement. When I first picked up The Secret History several years ago, at the recommendation of my now-husband, I knew very little about either the novel or its author; I was certainly unaware of the fact that Donna Tartt is a convert to the Roman Catholic faith. My first clue regarding Tartt’s religious affiliation came from an interview in the back of my edition of The Secret History, in which she listed Flannery O’Connor and Evelyn Waugh among the writers who have most influenced her. Since then, I’ve heard Tartt discussed on a couple of theologically-minded podcasts (Godsplaining, which is produced by the Dominican Friars of the Province of St. Joseph, and Dr. Jennifer Frey’s Sacred and Profane Love), but I’ve been able to find virtually nothing written by scholars or journalists about how her faith informs her art. Indeed, I was recently perusing Dana Gioa’s The Catholic Novelist Today and was disappointed to find no mention of Tartt.

Of course, this is partly because Tartt’s Catholicism lurks very much in the background of her work. Her novels are primarily gripping and compulsively readable stories—not vehicles by which to deliver a neat and tidy moral message. Perhaps to some, Tartt does not fit the bill of a ‘Catholic novelist’ and is merely a novelist who also happens to be a Roman Catholic. But Tartt herself provided insight into her understanding of the vocation of the writer in an essay that she contributed to a collection on The Novel, Spirituality, and Modern Culture. She suggests that “[in] a world without God, the only way we can see actions and their complex consequences played out in the fullness of time is through the novel.” The Catholic novelist does not need to take her characters to Mass or make them pray the rosary; it is enough simply for the novel to convey that the world is not a meaningless void but is imbued with providential purpose.

The Secret History, published in 1992 and arguably her most beloved novel (though 2014’s The Goldfinch won a Pulitzer), might not initially strike one as a story about providence. After all, it recounts the murder of a young classics student by his group of close friends. But as narrator Richard Pappen attempts desperately to ingratiate himself with this supercilious cadre of Greek students, the reader comes face-to-face with the ineradicable human desire for belonging. Unraveling Richard’s own biases and failures as the narrator is key for understanding The Secret History as a whole.

Richard is a transfer student at Hampden College, coming to the New England liberal arts school from a pre-medical program in California. He remarks frequently on the nondescript character of his childhood and early adolescence, growing up amidst interchangeable strip malls and yawning expanses of highway that leave him with a past as “disposable as a plastic cup.” When he finds his way to Prof. Julian Morrow’s Greek class, he encounters a group of friends who are inescapably particular: authoritative Henry, waif-like Camilla and her twin brother Charles, shrewd Francis, and WASP-ish Edmund (known as ‘Bunny’).

Richard’s suburban background, accompanied by his lack of funds for extravagant dinners and foppish attire, sets him apart from the rest of the group. Later, as Bunny’s social niceties unravel while he inches closer and closer to a nervous breakdown, he pokes at Richard’s insecurity, subtly mocking him for hiding the markers of his lower-middle-class upbringing. Richard is beset by a near-constant anxiety, wanting nothing more than to be fully accepted by his friends even as he grows more and more distant from the rest of the college.

A reader familiar with the oeuvre of C.S. Lewis—as Tartt most likely is, given her background in philosophy and the classics—cannot help but call to mind his essay on “The Inner Ring,” which (like his novel That Hideous Strength) explores the allure and danger of insular, exclusionary social groups. The existence of these ‘inner rings’ is itself morally neutral, but the desire which they stir up in those wishing to be admitted to their ranks can be perilous. “Let Inner Rings be unavoidable and even an innocent feature of life, though certainly not a beautiful one,” Lewis writes. “But what of our longing to enter them, our anguish when we are excluded, and the kind of pleasure we feel when we get in?” It takes conscientious effort to resist the pull of the inner ring; we are naturally inclined to desire inclusion among its ranks. Lewis then issues a warning which illuminates Richard’s moral arc: “Of all the passions, the passion for the Inner Ring is most skillful in making a man who is not yet a very bad man do very bad things.”

It is Richard’s intense desire to enter into the inner ring of the Greek students that pushes him from weakness into sin. His craving for the good opinion of his friends prompts him to spend Christmas break—the two coldest months of a brutal New England winter—in an unheated attic, with no insulation and with a gaping hole in the roof. Any member of the group would have given him some money or an invitation to stay with them if he had only swallowed his pride enough to ask. Instead, he almost dies, taken to the hospital at the last minute by Henry, who has returned early from a trip overseas with Bunny.

Shortly afterwards, Richard discovers that Henry, Charles, Francis, and Camilla are planning to travel to South America … on one-way tickets. In one of the most suspenseful sequences of the novel, Henry ultimately prompts Richard to guess that they—he and the other group members except for Bunny—were responsible for the death of a local farmer, a casualty of their descent into a Bacchic frenzy, as they literally cast aside their reason through cultic rituals devoted to the god Dionysius.

He looked at me for a moment, and then, to my utter, utter surprise, he leaned back in his chair and laughed.

“Good for you,” he said. “You’re just as smart as I thought you were. I knew you’d figure it out, sooner or later, that’s what I’ve told the others all along.”

But of course, Richard only figured it out with Henry as his guide. Henry is no stranger to the intricacies of human motivation; he expertly manipulates Richard’s desire to be held in esteem by this group of friends. Richard—insecure among the wealth and extreme intelligence of his fellow students—is finally given clear affirmation: “You’re just as smart as I thought you were.”In other words, he is one of them. Richard might have left this encounter and gone straight to the police station. He might have walked to Bunny’s apartment and shared in his horror at the murder of the farmer.

It’s funny, but thinking back on it now, I realize that this particular point in time, as I stood there blinking in the deserted hall, was the one point at which I might have chosen to do something very different from what I actually did. But of course I didn’t see this crucial moment then for what it was; I suppose we never do. Instead, I only yawned, and shook myself from the momentary daze that had come upon me, and went on my way down the stairs.

The defining moment for Richard’s part in the eventual murder of Bunny is not when he’s standing with the others on the edge of the cliff, about to push him over to his death. It is when he takes the proffered hand of the inner ring and turns a blind eye to their collective and unrepented sin.

Henry’s calculated flattery of Richard—and the perilous exclusivity of the group of friends—calls to mind the teachings of the Gnostics, which were prevalent in the 2nd century and which have continued to exert influence throughout the centuries. The term ‘Gnostic’ connotes a special kind of knowledge which the adherents of Gnosticism sought to attain. Bentley Layton, who has compiled many of the texts of their scriptures, describes the Gnostics as exclusionary, hostile to outsiders, and prone to the use of ‘in-group’ language. Indeed, for the Gnostics, salvation hinges upon the cultivation of a special body of knowledge, not accessible to the common man.

Such a disdain for the common permeates the behavior of Henry, Francis, Charles, Camilla, Richard, and—albeit to a lesser extent—Bunny. The desire to achieve the heights of Bacchic ritual does not differ tremendously from the recreational drug- and alcohol-fueled pursuits of their less-esoteric peers at Hampden. But the Greek students do not merely desire otherworldly pleasure or self-forgetfulness; they crave the thrill of eccentricity. Judy Poovey, the costume design student who lives down the hall from Richard, increasingly strikes me as an underappreciated character in the novel. She spends her time in a haze of substance use and gossip about the appearances and personal lives of her fellow students. Though Richard falls back upon Judy’s company whenever he is excluded from the inner circle of the others, he views her with distaste and condescension. Judy Poovey’s motivations, however, are not so very different from those of the inner ring; she is just more comfortable with her own desires and in her own skin.

Tartt has herself commented that The Secret History could be described as a novel of repressed sexuality. This is another feature of Gnosticism: since salvation is attained through knowledge, the body is at best a useless appendage to the soul—and, at worst, a hindrance to virtue and a source of evil. The Gnostic tendencies of the group can be seen in the disordered relationship that each member has with his or her body. Henry, who spends his time immersed in translations from obscure languages and who is the ringleader of the bacchanal, clearly prefers to hold himself apart from his own corporeality, almost forgetting he isn’t a brain with a pair of spectacles attached. The twins Camilla and Charles—proving correct an aspersion cast by Bunny—periodically engage in incestuous sexual activity, and Charles descends deeper and deeper into alcoholism. Francis, who is gay, lives in a near-constant state of torment and unease regarding his sexuality. And Richard, though he is more comfortable with sex than the others, is inclined to suppress other physical needs in order not to compromise his standing with group—as when he, as previously mentioned, nearly froze to death at his winter break accommodations. Furthermore, though he himself is willing to indulge in the physical pleasures of the ordinary Hampden students, he views the ethereal character of his friends as the ideal. Even his attraction to Camilla is couched in terms more befitting a ghost than a woman.

Bunny, however, poses a glaring exception to the incorporeal tendencies of the rest of the Greek group. The others are prone to vices such as envy and pride—even, for example, Charles’ abuse of alcohol is a manifestation not of gluttony but of these more insidious sins. But Bunny’s typical failings are emphatically those of the flesh, as he grasps indiscriminately at the pleasures that food, wine, and wealth have to offer. Unlike the others, he has a steady girlfriend, he enjoys sports, and he comes from a large family that includes multiple small children. Furthermore, he lacks the patience with the others’ bacchic experiments. There are myriad factors that contribute to the group’s turning against Bunny, but their distaste for his indisputable physicality lurks always in the background.

The distaste for the bodily is, of course, most evident in the students’ urge to enact a bacchanal—to summon the god Dionysius and to transcend the limits imposed upon them by the flesh. When Henry reveals that the farmer was murdered during a successful attempt at a bacchanal, Richard initially expresses confusion. Why would they have wanted to spend weeks performing rituals in order to revert to a pre-intellectual state? Henry, however, thinks it goes without saying: “‘After all, the appeal to stop being yourself, even for a little while, is very great,’ he said. ‘To escape the cognitive mode of experience, to transcend the accident of one’s moment of being.’”

Henry has, of course, internalized the comments made by the charismatic Prof. Julian Morrow at Richard’s first Greek class. In a discussion about Dionysian ecstasy, Julian makes the claim that “all truly civilized people . . . have civilized themselves through the willful repression of the old, animal self.” However, the ancient Greeks—unlike the Romans—did not live in denial of “emotion, darkness [and] barbarism,” and were no strangers to the experience of losing control:

To sing, to scream, to dance barefoot in the woods in the dead of night, with no more awareness of mortality than an animal! These are powerful mysteries. The bellowing of bulls. Springs of honey bubbling from the ground. If we are strong enough in our souls we can rip away the veil and look that naked, terrible beauty right in the face; let God consume us, devour us, unstring our bones. Then spit us out reborn.

For those of us living in the 21st century, any discussion of leaving behind the order and control of our humanity tends to provoke discomfort. But there is an analogue between what appeals to Henry in the bacchanalia and what is achieved in the Christian life.

Theosis, or deification, is the doctrine that holds that the human person, in the course of his or her salvation, becomes God (some prefer to say godlike in order to lessen the shock of the phrase, but this does, I think, a disservice to the fundamental claim that we are ultimately called to perfect union with the Triune God). Athanasius was referring to the necessity of the Incarnation for our deification when he famously stated that “God became man so that man might become God.” Theologians who write about deification tend to consider it according to different “dimensions,” two of which bear upon a Catholic reading of The Secret History: the ethical dimension and the mystical dimension.

Deification as an ethical phenomenon occurs here on earth; as a person becomes more virtuous, he becomes more and more like God. Christ gave us the example par excellence of how to do this, as He poured out His life for our sake. This is the self-forgetfulness to which human beings are called—not the frenzy of the bacchanal but the kenosis, or self-emptying, modeled by Christ on the cross. In their desire to perform a bacchanal, the Greek students are narrowly focused on their own experience. But we are made to forget ourselves in and through the service of others.

What about the mystical dimension of deification? This is fully realized only in the eschaton, as we become truly united with God for all eternity. It is perhaps the desire for this unity that ripples beneath Henry’s urge to “transcend the accident of [his] being.” For the Catholic Christian, however, grace does not demolish nature but perfects it. In becoming God, we do not lose ourselves; we become who we were created to be.

The students, therefore, are driven by an impulse that is not so very far away from the one that animates the Christian life. We are called, in a way, to let God “consume us.” But, crucially, this is not the god Dionyius but a God who also gave Himself up to be consumed by us (Matthew 26:26).

The text is ambiguous on the question of what really happens during the bacchanal. Is it a psychological phenomenon—aided by ingested substances—that leads the students to black out and murder the farmer? Or is something more sinister—and demonic—going on here? Your judgment of this will, in turn, shape your reading of the dream sequence at the novel’s close. Is Richard merely dreaming? Or is Henry perhaps a tormented soul—in Hell? Or Purgatory?—come back to relay a message?

I would, of course, argue in favor of a reading of The Secret History that is more spiritual than psychological. And this is most of all supported by a key scene in the epilogue. There is a wistful tone to these closing pages, as Richard graduates from Hampden, goes on to pursue graduate studies in literature, and drifts apart from his friends, all in the wake of Henry’s death. Richard’s pensive narration puts a distance between this period and his time at Hampden, leading the reader to think of him as a much older man, when in actuality he is still in his twenties.

After Francis attempts suicide—driven by guilt over Bunny’s death and by inability to realize his sexual desires—Richard and Camilla rush to visit him in Boston. (Charles, who suffers from alcoholism, has at this point disappeared from the narrative). Francis is discharged from the hospital on Ash Wednesday, and the three friends find themselves at church:

Camilla and Francis wanted to go to mass, and I went along with them. The church was crowded and drafty. I went to the altar with them to get ashes, shuffling along in the swaying line. The priest was bent, in black, very old. He made a cross on my forehead with the flat of his thumb. Dust thou art, to dust thou shalt return. I stood up again when it was time for communion, but Camilla caught my arm and hastily pulled me back. The three of us stayed in our seats as the pews emptied and the long, shuffling line started towards the altar again.

This is as far as the novel lets the reader see into Richard’s future. The Secret History is, one could argue, as though Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited closed after the end of Julia Flyte and Charles Ryder’s relationship—instead of after Charles’ conversion. At the end of The Secret History, Richard is far from achieving any kind of peace. But with this brief episode, Tartt is hinting that he might eventually find it—and that it will take the same form as the ashy symbol pressed onto his forehead.

In the Body of Christ, Richard could find the belonging, the intimacy of knowing and being known, that has eluded him all his life—for even the apparent security of the inner ring shattered in the years following Bunny’s murder and Henry’s death. He could approach the Eucharist alongside the Christian community, one of many in the “long, shuffling line.” Furthermore, the words of the priest (“Dust thou art…”) serve as a reminder not that his body is evil or unnecessary, but that it was formed by an all-loving, all-powerful God for the ultimate purpose of union with Him.

But he’s not there yet. Camilla, knowing this, pulls him back when he moves to receive the Eucharist. He has separated himself from God and a reconciliation needs to take place. While the Eucharist is as of yet off-limits, the ashes are open to all three of the friends. Mark the Ascetic, a 5th century theologian and a saint of the Orthodox church, writes that our deification is evident in the repentance that marks the entire life of the Christian. The cross of ashes thus represents a point of contact with the divine that the bacchanal never could.

The Secret History closes not with an administration of justice or a dramatic conversion, but with a glimmer of the divine. The hidden hand of Divine providence is hinted to be at work. Tartt has therefore successfully carried out what she sees to be the task of the Catholic novelist. To borrow a turn of phrase from Flannery O’Connor’s excellent lecture on “The Catholic Novelist in the Protestant South,” The Secret History might not be Christ-centered, but it is certainly Christ-haunted. And that, I think, makes it a fitting piece of Christian art for our time.