A clash of metaphors, for a dichotomy: is history, as Rust Cohle (Matthew McConaughey’s character on the hit first season of the American TV series True Detective) describes it, “a flat circle,” or does it progress, flowing like a river, full of unique moments, resembling the remark of the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who said “it is impossible to step twice into the same river”?

The former has been called the Greek philosophy of history—to the extent that it is true to use a phrase for a Greek that the Germans popularized—and the latter was brought into being by the people of Israel and their Christian heirs, who, reflecting upon their history and inspired by the Holy Spirit, provided our civilization with an account of history as linear, beginning with the fall of man and ending with apocalypse—the final unveiling where almighty God, “unto whom all hearts are open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid” (as the Anglican Collect for Purity prayer has it), reveals Himself and the secrets of all human hearts, separating the sheep from the goats in a final judgment before He brings about a new heaven and a new earth.

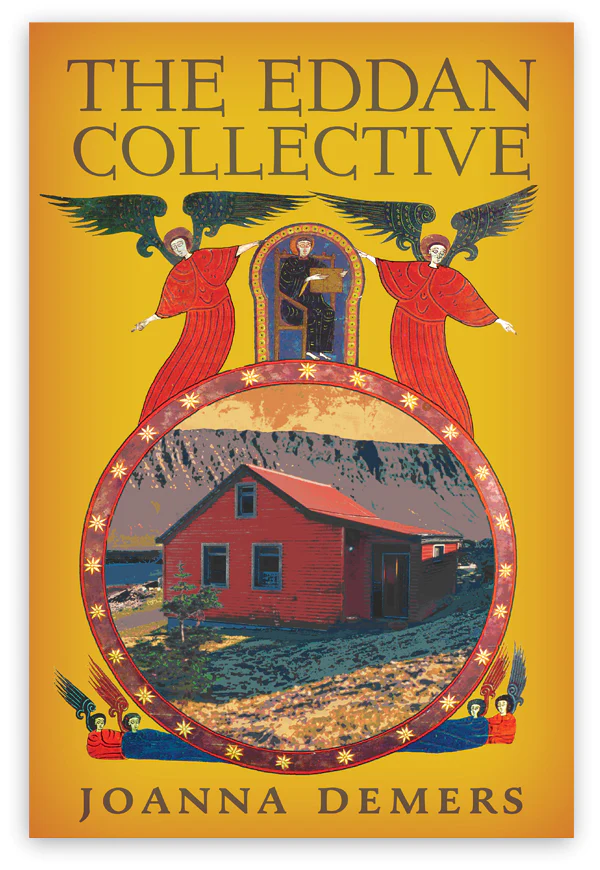

But as American lyricist and singer Lana del Rey recounts in her song “Text Book,” “Old Man River keeps running, with or without Him.” The linear account of history survived the near-total de-Christianization that has by and large purged orthodox Christians from academia, but in so doing, that account underwent a transformation into the progressive idea of history, whereby history sought to work out the perfection of some force (whether Geist or Spirit for Hegel or the material of class conflict for Marx). For readers to whom not only does this question appeal but also my idiosyncratic account of it—where fictional characters meet philosophers and pop singers—Joanna Demers’s new novel, The Eddan Collective, will provide fruitful reflection on and enjoyment of the strange nature of history, including the place of the individual soul and the arts within it, the curiously cyclical nature of some modern illnesses, and even suggests an answer to the recurring question, “Where should we turn our gaze when the heavens seem to fall about our ears?”

Demers’s novel is framed as a found manuscript, a venerable tradition in the novel stretching back to Cervantes’ Don Quixote and Manzoni’s Promessi Sposi, but intriguingly enough, The Eddan Collective does not have the third-person narrative perspective that characterized those works, but rather the first-person introspection of St. Augustine’s Confessions, the choice of which is thematically significant. After a brief preface from the 23rd century, we encounter the narration of Annika Trent, a lonely academic and quasi-invalid woman stricken with a chronic illness that neither routine tests nor bone marrow biopsies can identify.

Some illnesses, such as the flu or the common cold, tend to enhance our sense of ourselves as human beings as homo technicus, able through our superior knowledge—no longer delivered from above, like fire that Prometheus stole from the Olympian gods but stripped from Nature’s bare carcass by scientist-scavengers—to conquer what ails us. But other illnesses that resist easy diagnoses and treatments, if not cures, test our sense of selfhood and our supremacy above the kingdoms—animal, vegetable, mineral, and microbiota alike.

Joshua Hren describes a feeling consequent upon that cryptic chronic disease, Lyme, in a memoiric story, “This Sickness Is Not Unto Death.” “Lyme is supposed to be an invisible illness. Making it public only furthers frustration.” Likewise, Annika’s sickness, while being hidden from her academic colleagues and students, feels public, “an auto-immune condition” exhibiting “the symptoms of multiple diseases: the inflammation of lupus, the hematopoiesis of leukemia, the constitutional impairment of myelofibrosis.” Beyond the clinical talk lies the quotidian reality. As Annika sums it up, “My face is routinely flushed, and my cheeks and upper lip have always looked as if I had a sunburn. I am sweaty and bloated. My bones often ache.” And, most seriously, “No one has ever thought of me as beautiful.”

This last, however, is less an assessment of reality than a counsel of despair, a struggle with which both Hren and Annika wrestle. For Annika’s illness seems strangely connected to her ability to hide herself into a realm deeper than that visible to those with only literal sight. She is able to “send herself away,” whether to the Hippo of the time of St. Augustine or to the apartment of a colleague, and in such places she can not only converse with the dead but also read the minds of the living. When meeting Augustine and his religious brother and first biographer Possidius, she appears as a beautiful, “human-sized bird, with feathers that wee golden and emerald and beryl,” “the most beautiful creature [they] had ever beheld,” such that they see the beauty of her soul struggling for growth in charity. They imagine her as a malayka, a spirit that is not clearly evil, not a demon, but not clearly good, so not an angel—an in-between spirit in the process of becoming.

The preface to the memoir (purportedly penned by the 23rd century Center for Humanistic Studies) asserts that the memoir matters as a primary document in the history of the decline and fall of the American university, helping to reveal its formal transformation from the 21st century Social Justice U to the later Cloud College. However, Annika’s writing turns its readers’ gaze towards the persons she surveys, in states of spiritual decline or progress, despair or hope, or some odd oscillation between these various states.

Her illness and psychic transports reveal to her a typology hidden beneath the visible: the dean of the College of Arts and Humanities and Sciences is at once himself and the Roman Emperor Constantine, desperately trying to shore up a crumbling empire by simultaneously acquiescing to and attempting to co-opt a rising spiritual force. The members of her Eddan Collective (formerly the Center for Critical Studies of Capitalism) are “effete scholar-mendicants,” sneered at by the northern barbarians already marching on Rome, Hippo, and other cities. Her typological vision lies between Oswald Spengler’s Decline of the West and the Old Testament, and her sense of history curiously between St. Augustine and Hegel. But even as she begins her inquiry by assessing the study of Karl Marx, she retains something that die-hard Marxists to this day repudiate: a sense of the dignity of the individual human person.

As Spencer Klavan recently cited, witness Leon Trotsky, the supposedly milder Marxist when compared to Lenin, in a chapter recommending the use of terror: “As for us, we were never concerned with the Kantian-priestly and vegetarian-Quaker prattle about the ‘sanctity of human life.’” Annika’s concern with human life is shown in the very structure of her memoir: while concerned with large structures, it does not forget but rather dwells with singular souls searching for daybreak, such as her colleague Syd, his girlfriend Leta, and Herman Melville’s character Bartleby the Scrivener. It is by discovering the mercy they and others desire and speak of, even the mercy they offer, that Annika finds the courage to repent of her wrongs and seek the face of God through the mediation of a man who also witnessed the City of Man crashing about his ears but took heart in the promises of Him who offers a heavenly Jerusalem to those He calls.

The Eddan Collective reminds us that true progress for the city and soul ultimately consists in learning to wait for the good we do not deserve, “to wait for something good rather than decline or catastrophe,” in the City of God, which surpasses all infernal empires of men and whose peace surpasses all understanding.