In my part of the world, autumn feels like part of a secular liturgical year, however paradoxical that may sound. As the leaves change, stores fill with gourds, candles, and apple pies—as if by a similar natural cycle. Coffee shops introduce pumpkin-flavored drinks, apple orchards open for family-oriented events, and the frantic pace of life seems to slow down a bit. Many people’s homes seem to transform, as their usual color palate is replaced with (or at least complemented by) warm browns, reds, and oranges.

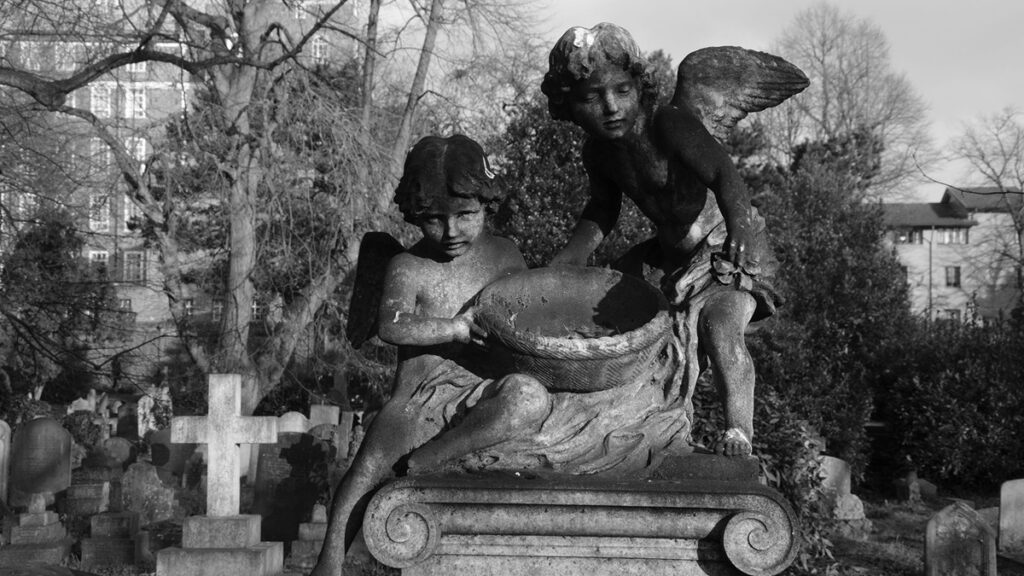

There is a certain tension to autumn, though. Even as it evokes cozy images of hay rides and singing around bonfires, its raison d’etre is the death of countless leaves, and the central secular holiday of the fall is Halloween. Not for nothing do some people call this time of year “Spooky Season,” and I myself quite enjoy watching the films of Hitchcock and reading frightening novels at this time of year. Though derived at least in part from the Christian observance of All Saints Day and All Souls Day, Halloween is often seen today as nothing more than a time to dress up in silly costumes and put up eerie decorations. I, for one, think the continuing—indeed, increasing—-popularity of Halloween in the United States speaks to an underlying desire for transcendence, albeit a desire that is often only half-sated by simulacra.

Though the secular calendar is by its nature never formalized, it can be theorized about. This theorizing often takes the form of condemnation, as when people criticize the consumerism inherent in Boxing Day and Black Friday, but it need not. I have previously written about Halloween through the prism of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, and today I consider another overlooked dark novel that provides the basis for an Alfred Hitchcock film, Marie Belloc Lowndes’ The Lodger. This novel, which is inspired by the murders of Jack the Ripper, initially encourages readers to consider evils outside themselves, but it ultimately forces them to confront the evil that exists within their own breasts.

Marie Belloc Lowndes (1868-1947) came from a family that would be worthy of discussion even if Marie herself had never achieved fame. Marie Belloc was born to an English mother and French father and was the older sister of famous Catholic writer Hilaire Belloc. Their mother, Elizabeth “Bessie” Rayner Belloc nee Parkes, was a well-known feminist writer in her day and a fascinating figure. Raised Unitarian, as an adult Bessie became interested in the Oxford Movement and followed the writings of its leaders. After becoming familiar with the social work of Catholic nuns, she entered the Catholic Church and raised her children in the faith.

Marie herself showed great promise from a young age, publishing her first story at just 16 years old. Her first book was a non-fiction work about the then-Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII), which she published anonymously in 1898. After publishing four more volumes of non-fiction in as many years, she turned her considerable talents to writing her first novel, 1904’s The Heart of Penelope. Over the next four and a half decades, she published dozens upon dozens of works. These were mainly novels and plays, but they included non-fiction books such as 1941’s I, too, Have Lived in Arcadia, which tells her parents’ love story, and her posthumous work The Young Hilaire Belloc.

Despite Belloc Lowndes’ great versatility as a writer, she has always been most appreciated for her novels focused on crimes and the mysteries surrounding them. These novels, though they deal with the macabre, are more concerned with inhabiting the minds of the characters living through frightening situations than they are about directly depicting any gore. Thus, they show evil in ways that humanize those committing it without ever justifying the crimes.

Belloc Lowndes would at times take inspiration from real-life events when concocting her dark tales, and the most famous instance of this was 1913’s The Lodger. Three and a half decades before the novel was published, eleven gruesome murders occurred in the Whitechapel district of London. Then known as a place of vice, Whitechapel was extremely impoverished, which sadly led many young women to turn to prostitution in order to procure the means to feed themselves and their loved ones. Of the eleven murdered women, all or most were prostitutes. These murders, which took place from April 3, 1888 to February 13, 1891, have all been ascribed—in the popular imagination, at least—to the same killer, who has been named “Jack the Ripper.” Over the years, a number of figures have been identified with Jack the Ripper; indeed, the Wikipedia page on the topic lists more than thirty-five suspects. Though historians are only confident that five of the murders were undertaken by the same assailant, the unsolved mystery of these murders has continued to fascinate people to this day.

One of the people interested in the case was Marie Belloc Lowndes. As she wrote later, she turned her attention to Jack the Ripper after a fateful meal:

I had once sat at dinner next to a man who told me that a butler and lady’s maid, who had been in his parents’ service, had married, and set up a humble lodging-house. They were convinced Jack the Ripper had spent the night in their house before and after he had committed the most horrible of his murders. I told myself that this might form the core of a striking short story.

The short story she wrote was indeed “striking.” So striking that she later turned it into a full-length novel.

The Lodger opens with a deeply moving chapter that introduces us to the Buntings, two retired servants who use part of their humble home in London as a boarding house. Despite the home’s handsome appearance and the fine furnishings it boasts, the Buntings are not well-off. They have scrimped and saved in order to have enough to buy their furniture at steep discounts. At the opening of the novel, they are living on the edge of poverty, with Mr. Bunting having pawned many of their prized possessions, quit smoking, and even given up one of his chief pleasures: reading the paper.

The novel’s style is reminiscent of Jane Austen’s mode of ‘free indirect discourse,’ in which narration moves seamlessly from describing action to expressing the minds of characters. As with most of the novel, the opening chapter shepherds readers into the mind of Mrs. Bunting, but it also gives a window into the psychology of her husband. With extreme pathos, Belloc Lowndes masterfully elicits sympathy for the plight of these two honest, aging, hardworking folks. Mrs. Bunting, it seems, is on the verge of losing her last bit of hope. The couple lives on the brink of poverty and homelessness, and readers feel the fear this engenders. Initiated into this world, those who did not know what was coming might begin to think this novel a Dickensian-style tale of narrow escape from destitution with a simple happy ending. But that is not how this story proceeds.

A knock comes at the door. Mrs. Bunting answers it, and there is a regal man with a single small bag. The stranger’s name is Mr. Sleuth. He says that he is looking to rent some rooms, one for himself and one for use for some experiments. Mr. Sleuth explains that he is a learned man who needs space and quiet for his work. If Mrs. Bunting agrees not to let any of their rooms to anyone else, he will pay them handsomely, more handsomely than the Buntings had dared hope for lodging and meals.

The Buntings take him in, and their lives improve immediately. Mr. Sleuth doesn’t eat meat, never drinks alcohol, and generally keeps to himself, all of which also means that he demands very little of Mrs. Bunting’s time or attention. The Buntings are able to enjoy better food than that to which they had become accustomed, and they begin to buy back the things that Mr. Bunting had pawned. Mr. Bunting even returns to his favorite habit of reading the daily paper again. And good timing, too, because a series of murders has all the city alight with speculation as to the culprit.

The murders—an amalgamation of Jack the Ripper’s and those perpetrated by the Lambeth Poisoner—are gruesome, and the police are desperate to catch the man committing them. As it happens, Mr. Bunting knows a young policeman named Joe Chandler well, the son of a longtime friend who has passed away. The kindly and good-natured young officer enjoys discussing the case with Mr. Bunting, who is always eager to hear the policeman’s perspective on the murder case.

Meanwhile, it becomes clear that Mr. Sleuth is a very odd man. Despite Mrs. Bunting’s insistence that he is a “real gentleman,” he has extremely strange habits. The lodger spends his days studying Holy Scripture. In and of itself, this would be a noble way of life, but it becomes clear that he obsesses over passages that can be interpreted to be in any way critical of women, understanding them in the most extreme way possible. Focusing on violent details in the Bible, the man is writing a commentary on the Good Book. He sometimes goes out very late at night, and afterwards, he spends time conducting “important research” during which he must not be disturbed.

Slowly but steadily, facts mount up, and Mrs. Bunting begins to suspect that her lodger might in fact be the killer whom all London wishes to see caught. However, she does not go to the police, even though it would be quite easy, given that a policeman, Joe Chandler, visits them so often. Even as evidence continues to accrue, she denies to herself that Mr. Sleuth could possibly be the murderer.

Readers might think that, were they in Mrs. Bunting’s position, they would have no trouble approaching the authorities. This was how I, at least, felt early in the book. But as the tale continued, I was forced to confront how subtle evil is, growing like a vine around our hearts and minds. True, my own personal complicity with evil has never been as dramatic as housing a man I suspected to be a murderer. But this novel’s story reinforces the reality, observed by Solzhenitsyn, that “The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart.”

There is an everydayness to the evil depicted in The Lodger. To echo Hannah Arendt, Mrs. Bunting’s sins of omission are banal, barely noticed or noticeable, even by herself. Like so many of us, Mrs. Bunting excuses herself more and more, though to find out whether she ever stops doing so you’ll need to read the novel yourself.

The Lodger is a book that confronts evil. But it is also, in doing so, a profoundly humane book. Its characters feel real—frighteningly so. And because of this, it is a book that, whether read in the dead of night on Halloween or midday on the brightest day of the year, stays with its readers, quietly reminding us that evil is afoot, right under our own roof.