Every spring, the world observes an odd holiday: Easter. On the first Sunday after the first full Moon following the spring equinox, Christians and non-Christians alike celebrate. For many in the West, this feast is little more than the chance to indulge their sweet tooths, decorate the home with images of giant rabbits, and maybe get the Monday after off from work. Easter’s true meaning, I need hardly mention, is of far more import than these.

But how does one approach Easter? This feast that, for the Christian, is superior even to Christmas? This feast that celebrates man’s liberation from sin? This feast that proclaims that those who die in Christ will be raised up bodily on the last day?

The Catholic Church has long provided an answer to the question of how to approach the great paschal feast: through Lent. During this forty-day period, the faithful are meant to engage in prayer, fasting, and almsgiving. By so doing, they unite their sufferings and joys with those of Christ and grow closer to Him. Human nature being what it is, this period of self-denial can help people prepare themselves for the celebration of Easter. It does this especially by forcing us to confront our limitations and sinfulness.

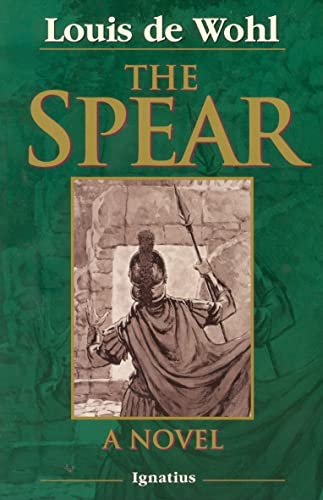

The season of Lent culminates in the Triduum, wherein the faithful relive the events of the Last Supper, Passion, and death upon the Cross of Jesus Christ. Yet, for those who have been observing these mysteries for years, the seeming familiarity of Holy Week can allow us to slip into a kind of auto-pilot. This is a danger Christians should confront whenever we detect it within ourselves. And one great way of confronting it is by reading Louis De Wohl’s epic historical novel of the Crucifixion, The Spear.

Louis De Wohl was born in Germany in 1903 to a Hungarian father and Austrian mother of Jewish descent. Christened Lajos Theodor Gaspar Adolf Wohl, the boy exhibited an early taste for artistic work informed by the faith. At the age of 8, he wrote a play called “Jesus of Nazareth.” He was motivated by his distaste for most popular works about Jesus that he had encountered.

By the time he made his proper literary debut at the age of 23, De Wohl had moved away from writing religious works. Instead, the novelist (who now went by the name of Ludwig von Wohl) mainly wrote exciting or comedic novels, sixteen of which were adapted into films. Over this period, though, he became so frustrated with the rising Nazi regime that he emigrated to England in 1935, where he would reside for decades.

After his move, he worked tirelessly to learn English so that he could write in his new language. However, his new English novels would be of a starkly different character from his German works. This shift was caused by a decisive encounter with Blessed Alfredo Cardinal Ildefonso Schuster, who told him point blank: “Let your writings be good. For your writings you will one day be judged.” From that time on, he began to write novels about the lives of the saints.

As someone who has long struggled to focus on spiritual reading, De Wohl’s novels are a great help, and Ignatius Press has done a great service by keeping these books in print for years. While De Wohl published many such works, one has always appealed to me above any other: The Spear. Published in 1955, the novel tells the story of Christ’s Crucifixion and the centurion who pierced his side with a spear. Traditionally, this man has been known as “Longinus,” and he has long been venerated as a saint. De Wohl uses this relatively scant information to great effect, using Saint Longinus as an entrance, not just into the ancient world, but into Jesus Christ’s life and Crucifixion.

The Spear begins with a fabulous party in ancient Rome. Cassius Longinus, who has fallen head over heels in love with a woman named Claudia Procula, shows himself to be a talented but prideful young man. Coming from a well-known family with a proud military history, the young Longinus is confident in himself. He is so confident that, in order to embarrass his host and impress the beautiful Claudia, he makes a bet that he can hit a shield with a spear from a great distance. This he does, but not without making a powerful enemy in his host, Balbus.

I don’t want to spoil the tale of how Cassius Longinus’ life is torn apart by Balbus, but suffice it to say that Longinus ends up completely alone in the faraway land of Jerusalem. At this point, the story begins to alternate between sections about the Jewish inhabitants of the land and the Romans, allowing us to get to know Pontius Pilate and Barabbas as well Saints Martha and Mary Magdalen, to name but a few. De Wohl convincingly depicts the political intrigue that surrounds Christ’s death, helping readers to consider at length what in the Gospels is often covered by just one or two lines of text.

The form of the novel is striking. The Spear is not a pure hagiography: it does not merely collect legends associated with popular devotion to Saint Longinus. Instead, De Wohl attempts to place readers within Longinus’ world, bringing them to the very foot of the Cross. The book is the fruit of careful study of the Gospels, but it is also a work of imagination. This, I think, is its value. The Spear serves as a lectio divina of sorts, that is, as an opportunity to imagine oneself in the action of the Holy Scriptures.

From the moment it begins, the novel builds up tension, moving towards the inevitable conclusion of the Crucifixion of Christ and all its mighty aftermath. To read The Spear is to find oneself in a world quite different from one’s own. And yet it is a world that has formed the world in which we live today, as well as the faith many still hold. Reading De Wohl’s imaginative portrayal of St. Longinus’ life and the chaos surrounding the days leading up to Christ’s Crucifixion can help readers enter more fully into their observance of Holy Week and, ultimately, the celebration of the Resurrection that is Easter.

The Christian life requires those who embrace it to live within seeming contradictions—a life of paradoxes, as Chesterton famously characterized it. There are many examples. Christ enjoins His followers to be wise as serpents but harmless as doves. Christians are taught to despise the world and yet love their neighbors. The faithful believe that the only way to be truly oneself is to accept God’s grace, denying many of one’s seemingly natural proclivities.

One of the seeming contradictions that The Spear helps to illuminate is that between the mourning of Christ’s death and the celebration of His Resurrection. The Spear forces readers to spend a significant amount of time awaiting the Crucifixion, and consequently there is a certain sense of dread hanging over much of the novel. Rome is an old empire, one that has ceased to deserve the sense of fidelity it demands. Full of bureaucracy and petty grudges, it lurches towards its end. Meanwhile, most of the Jewish leadership in Jerusalem grasps at control, ultimately putting to death the One who offers them a way out of their futile power plays.

The novel clearly shows man’s sinfulness and need for Christ’s redeeming grace. Even Longinus, the most virtuous non-Christian (or perhaps ‘pre-Christian’ is more apt), is still not motivated by the love that brought the Son of God to earth. Instead, his virtues are, as St. Augustine put it, but “splendid vices.” Motivated by the desire for revenge, Longinus shows great restraint, but this restraint is always tainted by his own sin. This sin, and every other sin, cries out for either punishment or forgiveness. God, in His love, offers the latter to those who accept His grace.

In the Crucifixion, Christ took all our sins onto Himself. This is a claim so familiar that we may easily overlook its magnitude. Seeing this offer through Longinus’ eyes, however, allows readers to reckon with the enormity of Christ’s act. It is horrifying, bloody, and brutal, and we caused it with our own sin. Just as Longinus thrust his spear into Christ’s side, so each reader, in the many times we reject God’s grace, contributes to the suffering of Calvary.

After the Crucifixion, though, comes the Resurrection. After the Harrowing of Hell, Christ returns to earth in His glorified body. This stands as a testament to the promise that those who die in Christ will one day rise as He rose. This is what we celebrate at Easter. We celebrate the day when Christ rose from the dead, nevermore to die, and we anticipate the day when, God willing, we shall rise from our own graves to live with the Blessed Trinity for all eternity.

And yet, Christ’s glorified body retains the wounds of the Crucifixion. Even in Heaven, his hands and feet have holes, and his chest is still punctured from St. Longinus’ spear. This should take us aback, even if we have meditated on it before. Heaven is perfect, is it not? How, then, can the wounds inflicted by sin remain?

Far be it from me to answer this question with a simple answer, but I will point to The Spear. It is only through his great sin, pain, and loss that Longinus, in De Wohl’s telling, is able to allow God to open His heart. To again echo St. Augustine: in Heaven, our forgiven sins stand as trophies of God’s mercy. While the Christian regrets his sin, it simultaneously shows the effects of Christ’s love. The Resurrection happens only after the Crucifixion, and Easter comes only after Lent and Holy Week. St. Paul tells us that “where sin abounds, grace abound all the more.” So it was in the life of St. Longinus, and so it may be today. Reading The Spear this Lent, I have been forced to confront the reality of the sinfulness that I see in myself and in the world around me. Like St. Longinus, I live in a declining empire that has lost much of what once made it worthwhile. Like him, I am often motivated by my own pride rather than by charity. Like him, I am in constant need of God’s grace. Our world has much in common with the ancient world De Wohl depicts, and it has just as much need for Christ this Holy Week as it did the first.