If you have spent any amount of time among conservatives and reactionaries in the Anglosphere, particularly Catholic ones, there are certain figures and ideas you are used to hearing about. Chesterton’s many aphorisms have probably been quoted (and misquoted) at you time and again. You’ve heard John Adams’ claim that the American Constitution was “made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” You’re used to people invoking Hilaire Belloc’s position that “The Faith is Europe.” Regardless of which of these you most appreciate, you are almost certainly accustomed to people invoking the fantastical tales of John Ronald Reuel (J.R.R.) Tolkien.

This is understandable. Tolkien, a devout Catholic of a decidedly reactionary bent, was the author of The Hobbit, a wonderful book that many children are raised on to this day. The tale of Bilbo Baggins leaving his comfortable hobbit hole, encountering terrors, besting an evil dragon, and returning to his beloved home is not just entertaining, but it also deeply informs many people’s moral imaginations. His follow-up, the monumental Lord of the Rings, is a sprawling epic that, in addition to enthralling hundreds of millions, is an extremely fertile place to look for conservative cultural and political metaphors. In addition, Tolkien wrote several short fiction pieces, much academic work, and the indispensable “On Fairy Stories.”

The book that was for him a life’s work, however, is one that many are hesitant to read: The Silmarillion. There are, as a general rule, two ways that The Silmarillion is mentioned in conversation. The first is as a punchline about boring long books, a sort of modern-day Leviticus. The other way—far more frightening to the general public—is when someone, usually a young man, attempts a lengthy, long-winded, seemingly interminable discussion of minutia that can do little other than bore to tears anyone who’s not steeped in Tolkienian lore. Due to these ways of speaking about the book, many people are understandably skeptical of picking up The Silmarillion. They worry that it will read like the Biblical genealogies, with Shmorfulgarp begetting Schnottengulf and ten-page discussions of mountain ranges.

While I was once among those who wrote off The Silmarillion, once I actually began reading it, I discovered how I wrong I was. For those who take the time to work through the book, it is far from boring. It is a unique book, one that brings readers through a wide span of fictitious history, making us fall in love with characters and challenging us to reflect on fundamental questions of fate and the purpose of our existence. It may even be, as Tolkien hoped it would be, the only genuine work of mythology developed in the modern age.

Despite the great popularity of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien always considered The Silmarillion to be his magnum opus. Perhaps because of this, he held it to an impossibly high standard, working on it for his whole adult life and never actually producing a finalized manuscript for publication. Instead, he constantly tinkered with—and at times completely changed—the characters, dates of events, and even the ultimate fates of heroes and heroines. Because of this, it wasn’t until after the author’s death that The Silmarillion was given a canonical form and released to the public. One of the author’s children, Christopher Tolkien, who had spent years as a sort of apprentice/assistant to his father, edited the work with the help of Guy Gavriel Kay. It was then published in 1977, four years after its author’s passing.

The Silmarillion is perhaps best described as a collection of myths composed by a single mind. Though all connected, the chapters have drastically different flavors. Some chapters feel metaphysical while others are mundane, some tell of great adventures while others are focused on stories of a smaller scale. Do not, however, get the impression that the work lacks form. It is made up of five sections, which are presented to readers in chronological order: Ainulindalë, Valaquenta, Quenta Silmarillion, Akallabêth, and Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age. The first two sections take place before and during the beginning of the world, while the other three are parts of the ‘history’ of Tolkien’s world. The middle section, the Quenta Silmarilion, takes up the bulk of the work, and it tells the story of the “silmarils,” gems of great power that are coveted by many.

Don’t worry if you found that a little overwhelming—you definitely don’t need to remember the finer points of The Silmarillion’s structure to appreciate the beauty of the stories within. To make that clear, I’ll focus on the opening of the work and use it to introduce the world of The Silmarillion.

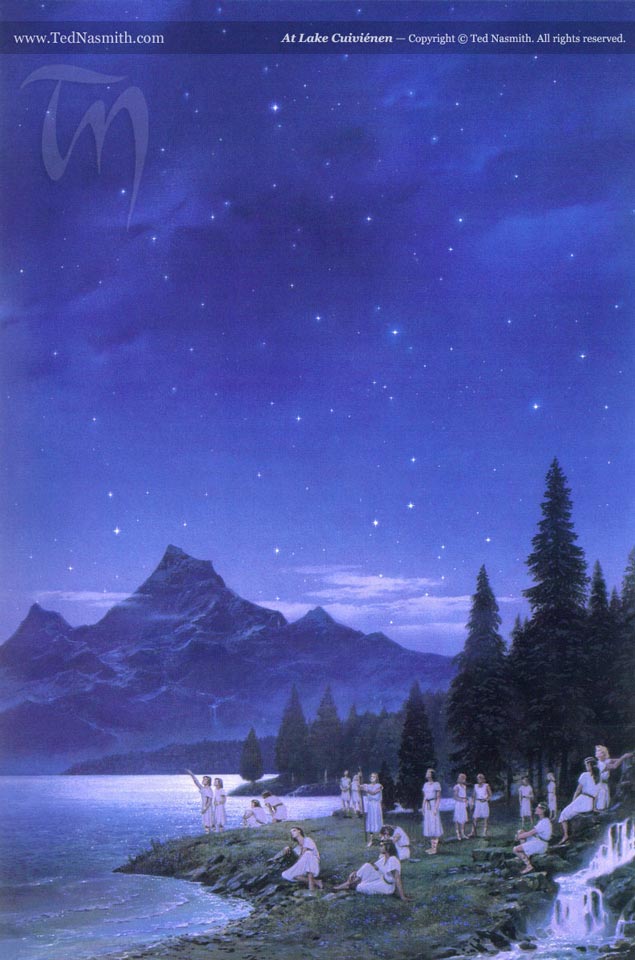

The opening section, “Ainulindalë,” tells the story of the creation of Eä, the material world, which includes “Middle Earth.” If the book of Genesis describes creation with an emphasis on the earth, Ainulindalë focuses on the heavens. The God of Tolkien’s legendarium, Eru Ilúvatar—whose names mean, respectively, “the One” and “allfather”—creates the Ainur, the equivalent of angels. And just as Biblical angels are sorted into ranks and kinds (seraphim, cherubim, thrones, dominions, etc.), so the Ainur are divided into the superior Valar and the Maiar, their assistants.

If you are feeling overwhelmed by the preceding explanation, don’t worry: this is where the myth’s beauty unfolds. The book tells of how the Ainur begin to sing according to Eru Ilúvatar’s will. In Tolkien’s own words:

And he [Eru Ilúvatar] spoke to them, propounding to them themes of music, and they sang before him, and he was glad. But for a long while they sang only each alone, or but few together, while the rest hearkened; for each comprehended only that part of mind of Ilúvatar from which he came, and in the understanding of their brethren they grew but slowly. Yet ever as they listened they came to deeper understanding, and increased in unison and harmony.

This song, called “the Music of the Ainur,” is a sort of plan for the creation of the world and its unfolding through history. Under Ilúvatar’s guidance, the Ainur sing out the divine project, being co-creators of the world. On re-reading this section, I am tempted to just repeat every one of Tolkien’s gorgeous descriptions. I will satisfy myself with just this one, though:

Then the voices of the Ainur, like unto harps and lutes, and pipes and trumpets, and viols and organs, and like unto countless choirs singing with words, began to fashion the theme of Ilúvatar to a great music; and a sound arose of endless interchanging melodies woven in harmony that passed beyond hearing into the depths and into the heights, and the places of the dwelling of Ilúvatar were filled to overflowing, and the music and the echo of the music went out into the Void, and it was not void.

However, one of the Ainur, Melkor, became self-willed. Uninterested in Ilúvatar’s plan, he began “to interweave matters of his own imagining that were not in accord with the theme of Ilúvatar; for he sought therein to increase the power and glory of the part assigned to himself.” Ilúvatar, however, is able to make use of Melkor’s dissonance, crafting a symphony that integrates and resolves the revolt against his will.

If this is beginning to sound familiar, that isn’t surprising. Melkor is a figure much like Lucifer, the fallen angel of Christian theology who is often called the Devil. Having sown discord in the celestial music, Melkor descends into the world after its creation. In so doing, he becomes the ultimate antagonist that all the many protagonists of The Silmarillion face. That is why the book must take on such a massive historical scale: it allows readers to see how Melkor’s actions reverberate through the world, and also how Ilúvatar’s providence makes use of it, especially through the tale of the silmarils.

One striking aspect of Tolkien’s work is how he blends the power of pagan myth with a Christian sensibility. While he famously held that his works were not allegorical, they are clearly imbued with the creative awareness of a man of deep Christian faith who spent his professional life studying language and the myths expressed throughout its history. Perhaps no work of Tolkien’s expresses these two aspects of Tolkien’s mind—pagan mythology and Christian sensibility—more than The Silmarillion.

Throughout the work, the narrator refers at crucial points to a given character’s—or city’s—“doom.” When the reader first comes upon that term, it might seem as though Tolkien is forecasting the downfall of everything whose doom is predicted, but that is not quite how the author uses the term. Instead, by “doom” he means something more like “fate” or “destiny.” Why, then, would he chose to use a term so laden with negative connotations? While I cannot speak to his etymological rationale, there is one thing that is clear to me as a reader: the term “doom,” even when used in as value-neutral a way as possible, always has a slight sense of foreboding and powerlessness. Doom, then, is what awaits the many inhabitants of Eä as they face off against Melkor.

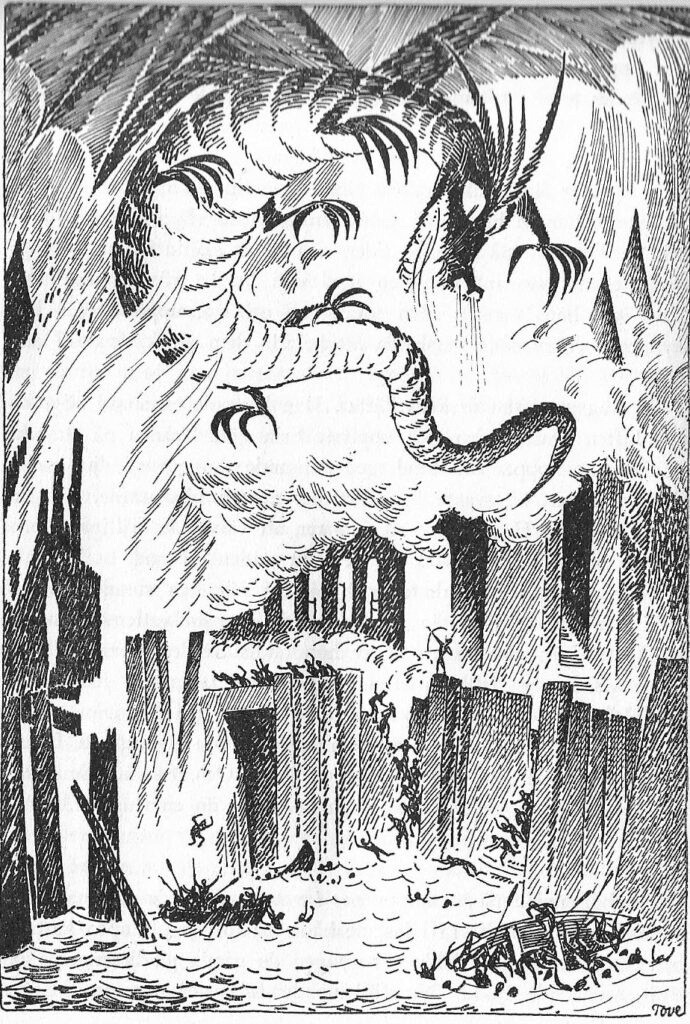

This doom was the fate of those great pagans of antiquity who attempted to build healthy civilizations, or even just happy lives. At any time, the evil of this world could encroach and destroy all that they loved. Without the shield of Christ’s sacrifice, they were left defenseless against the moral slings and arrows of a beautiful but cruel world. Some tales in The Silmarillion, then, can leave readers with a sense of futility. The book includes the “three great tales of Middle Earth,” the Children of Húrin, Beren and Lúthien, and the Fall of Gondolin. Of these, two are frankly heartbreaking. The Children of Húrin tells the tragic story of one family, while the Fall of Gondolin tells the tragic story of a city.

Despite the futility and “doom” under which these characters live and die, there are moments throughout the work, most famously the tale of Beren and Lúthien, when hope shines through. I won’t spoil it, but this love story, inspired by Tolkien’s own marriage, has moments that feel more Christian than some of the more tragic pagan tales.

I have previously written about pagan myth and discussed its relationship with Christian art and culture. The Silmarillion, though, resists simple categorization as either pagan or Christian, and that is part of its power. It is no accident that Tolkien’s world is beloved of the traditionally religious and the secular alike. Think, for instance, of the founding myth described above. For the Christian, it has strong resonance with their theology, while for the irreligious reader it is a beautiful story that echoes the experience of artistic creation.

When reflecting on the cross-religious appeal of Tolkien’s work, I am reminded of “The Spirit and Writing in a Secular World,” an essay by contemporary Catholic novelist Donna Tartt. In it, she writes that

A good novel … enables non-believers to participate in a world-view that religious people take for granted: life as a vast polyphonous web of interconnections, predestined meetings, fortuitous choices and accidents, all governed by a unifying if unforeseen plan. Insofar as novels can shed light on human existence, this is how they do it. I think the reason that so many non-religious people have faith in the illuminating, humanistic, healing powers of the novel—in Tolstoy, Faulkner, Melville—is precisely because of this strong inner design. Something in the spirit longs for meaning — longs to believe in a world order where nothing is purposeless, where character is more than chemistry, and people are something more than a random chaos of molecules. The novel can provide this kind of synthesis in microcosm, if not in the grandest sense; it conveys the impression (if not the reality) of a higher, invisible order of significance.

The Silmarillion is a book that glides effortlessly between the great scale of world-shaking events and the small everyday details of characters’ lives. These intertwine beautifully and craft the story of a whole world. So too does God’s providence make use of world wars and marriages, presidential elections and the flutter of a sparrow’s wings.

Yes, reading The Silmarillion takes some getting used to. It has some odd names in it, and Chapter 14 is pretty boring unless you have a passion for geography (just skip it if you want), but it is a book of unique beauty. If you take the time to read it, you will find your mind enriched by the tales you encounter. And then you can do the only thing better than reading The Silmarillion for the first time: you can re-read it.