In recent weeks, a surprising trend has appeared on TikTok. A woman will post the recording of her husband’s (or boyfriend’s) answer to a simple question: “How often do you think about the Roman Empire?” There are hundreds of instances of women doing this and being shocked by the answer. Most men in the videos say at least once a week, but many say once or even a few times a day. The women in the video are invariably bewildered by this, wondering what could be so interesting about the Roman Empire.

There are, of course, many ways of responding to their bemusement and explaining the perennial interest the Roman empire (and ancient history in general) has. The study of ancient history is a pastime many men (and no small number of women) have enjoyed, but the enjoyment of history seems different from the enjoyment of more systematic intellectual endeavors like mathematics, theology, or astronomy, to name a few. These modes of investigation, each with its own subject of study and mode of investigation, are valuable because they claim to provide man with knowledge of that which is necessarily the case.

History, on the other hand, stands apart from these inquiries, as it is essentially a kind of storytelling. And stories—whether of real or fictional events—hold a unique place in human life, delighting, causing wonder, captivating the imagination, purging the emotions, and even encouraging moral growth. Thus, to say history is made up of stories is in a way to say that it is actually more essential to human life than disciplines like chemistry and physics, not less so.

Whether, like the wives and girlfriends in these TikToks, you wonder why anyone would think regularly about ancient Rome, or whether, like the men in the videos, you already have an appreciation for this city-cum-empire and want to learn more about it, you need look no further than the work of Roman historian Livy.

We know little about the life of Titus Livius. Livy (as he is best known in English) was born in either 59 or 64 BC in Patavium, now Padua. Placid and restrained as an adult, it is easy to imagine Livy calming soaking up Patavium’s well-known conservatism. Many in Patavium knew that the best way for a Roman to live was to strive for the virtue that—in their eyes—first made Rome great.

As a teenager, Livy witnessed civil wars turn citizen against citizen. The city of Patavium was particularly aggrieved in this conflict. This experience may have formed (or simply reinforced) Livy’s views that the Roman world was in a period of moral and political decline. It seems that Livy may not have been able to benefit from as much formal schooling as some from his city had in earlier generations, but he was very widely read nonetheless.

As a young man, Livy either moved to the city of Rome or just began to visit it regularly, but either way his attention was clearly focused on the city and its history. This began to bear fruit in his writings, as he started composing his magnum opus, a history of Rome, around the age of 30. He does not seem to have held any public office or even engaged in any public activities, choosing instead to focus his time and considerable talent on writing.

Ab urbe condita (“From the Founding of the City”) is a work of astonishing breadth. Covering the period from Rome’s founding until Livy’s own day, the work stood as a monumental 142 books. Sadly, only part of the work, 35 books, survives today, but this is more than enough to establish Livy as a canonical figure for Western history. The first ten books survive detailing Roman history until 293 BC, and nearly all of books 21-45 have come down to us, describing Roman figures and events from 219 to 166 BC. I confess that I have only read bits and pieces of the later books; there are some who criticize them as being drier and more formulaic—and thus less thrilling—than the earlier ones, which I do not dispute. The opening books of Ab urbe condita are made no less compelling because of this reality, and it is these I wish to focus on today.

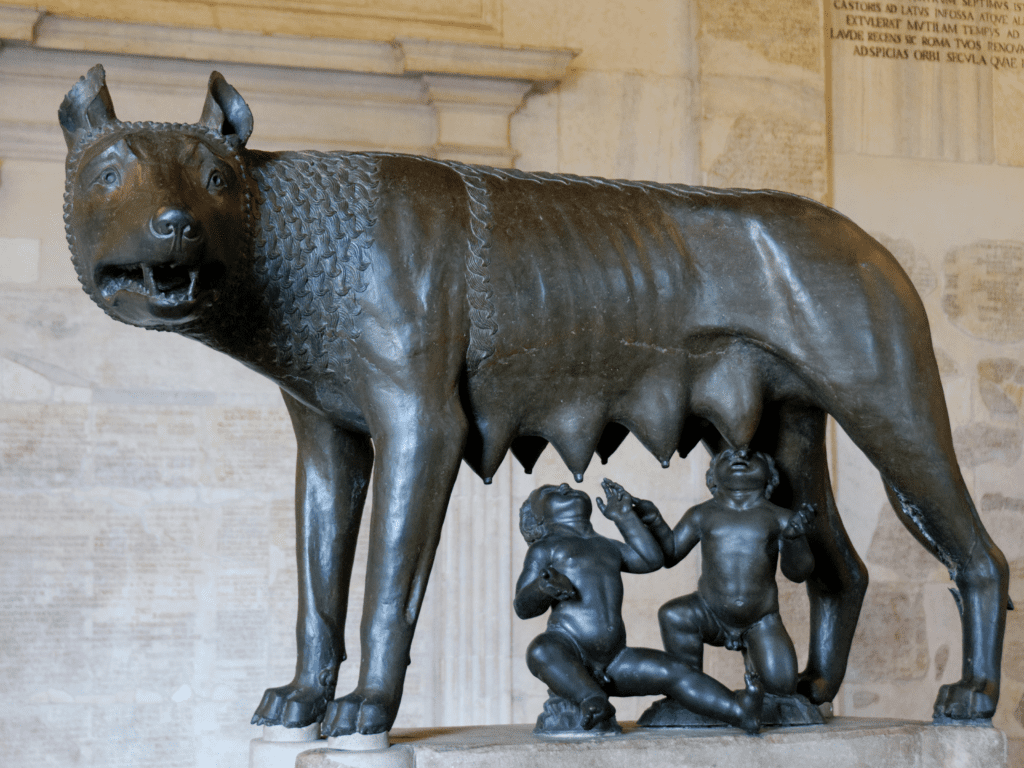

The story of Rome begins with Aeneas, the legendary hero of The Aeneid, whose descendant, Romulus, would go on to found Rome. The old story goes that Romulus and Remus were brothers born of a vestal virgin, and their father may have been the god of war, Mars. Since the vestal virgin was the daughter of a former king, Numitor, the man who had usurped the throne ordered them to be killed by exposure on the banks of the Tiber River. However, the god of the river (with the rather on-the-nose name of Tibernus), saved the twins, who were then nourished on the milk of a she-wolf before being adopted by a shepherd.

Though Livy is skeptical of the historical veracity of these myths, he carefully chronicles them, providing an honest overview of the accumulated traditions. This makes for great reading, as Livy knows a good yarn when he sees one, even when he thinks it’s an imaginary tale. He also occasionally ventures into historical debates about the truths that inspired Rome’s founding fables, as when he famously speculates that, instead of a literal wolf, Romulus and Remus may have been nursed by “a common whore [who] was called Wolf by the shepherds.”

In any case, the legend states that when Romulus and Remus were grown, they worked to topple the man who had usurped their grandfather’s rule. This accomplished, they were ready to found a new city. However, they argued over where it should be built. Eventually, Romulus murdered his brother, and Rome was born on the Palatine Hill. The blood of Remus is thus the seed of pagan Rome.

The legends surrounding the foundation of Rome and its early history were once well-known, but today they have become, like many Biblical stories, only hazy memories for many, even many conservatives. The stories of the seven kings of Rome are of perennial interest to anyone who wishes to reflect on the nature of government and the realities of regime change. But if it is true that the tales of Romulus, Numa Pompilius, and the other five kings of Rome are often overlooked today, this is even more true of the non-royals described in Livy’s work.

Perhaps my favorite of these stories is that of the Horatii, brothers who came to the defense of Rome in its early days. Romulus was a warrior king, but the second king, Numa Pompilius, was a pious man who was uninterested in battle. He did all he could to sculpt the Romans into a religious and peace-loving people. While he was successful in the first goal, his victory in the second was pyrrhic; war began almost the moment the next king ascended the throne. King Tullus Hostilius led the Romans to war against their neighboring city, Alba Longa. It turned out to be a costly war, however, draining both cities of men and resources. Thus, each city’s rulers agreed that a single battle would decide the war, and this is where the Horatii enter the picture.

It just so happened that Rome and Alba Longa each had a set of triplets who were mighty warriors. Alba Longa boasted the Curiatii, while Rome had three brothers with the name Horatius (plural Horatii). Rather than continue the brutal war, the Horatii and Curiatii would face off, and whichever family remained with at least one man standing would bring victory to his city. Livy’s brief description of the preparations for the battle are deeply evocative, and it is hard to read them without a bit of jealousy for the level of patriotism exhibited, not just by Rome and the Horatii, but even Alba Longa and the Curiatii. The battle itself sweeps readers along, and it feels almost cinematic; indeed, I would not be surprised to see a film version of the story a la the movie 300 someday.

Two Horatii are killed, with just Publius Horatius left to defeat all three Curiatii. Publius was unharmed, and he knew that his slain brothers had weakened the Curiatii. But he also knew that, even wounded, three against one did not make for good odds. An agile runner, Publius Horatius sped away from his enemies. The fastest of the three pursuers came close to his prey, but Publius turned, defeated him, and continued running. He then did the same with the second of the Curiatii. Finally, he was left with just one enemy and shouted, “Two I have offered to the shades of my brothers: the third I will offer to the cause of this war, that the Roman may rule over the Alban!” and he plunged his sword through the last man’s throat.

Rome, then, gains power over all of Alba Longa, and its many victories began to rack up. Over the centuries, Roman warriors could look back on the bravery and cunning of the Horatii as a noble example of their ancestors and forerunners. So today can this tale serve us in our own battles. Though we are unlikely to face off with our brothers in combat for the fate of our home city, we can learn to face the challenges of life with the kind of courage and determination shown by the Horatii.

Whether it is new to you or very familiar, hopefully the story of the Horatii has whetted your interest in reading (or re-reading) Livy’s work. While I could happily tell more stories from Ab urbe condita, I instead propose we take a moment to examine Livy’s preface to the first book in order to reflect on the value of studying Rome in particular and ancient history in general.

Taking up only about two pages in contemporary editions, this preface is, to my mind, one of the greatest reflections on the import of history in the whole of ancient literature. He begins by humbly confessing that he is unsure whether his work will be worth writing, much less reading. What he is attempting is “an old and hackneyed practice,” and he thinks it is foolish that “later authors [are] always supposing that they will either adduce something more authentic in the facts, or, that they will excel the less polished ancients in their style of writing.” This prescient observation reveals to contemporary readers that ancient historians could fall prey to the same progressive fallacies that so ail many contemporary academic historians.

Despite implicitly claiming that his talents do not surpass the historians that have come before him, Livy sets out to write his history. He explains that doing so will at least “be a satisfaction to me that I too have contributed my share to perpetuate the achievements of a people, the lords of the world.” This is, I think, central to Livy’s view of history. Man has a desire to know the past, and, more importantly, he has a need for moral exemplars.

Every human culture has had people whom it holds up as examples of how its people ought to live. Some, like the Horatii, show great bravery, while others display profound compassion, others perseverance, and still others impressive temperance. The Roman founders were not perfect people, just as my own nation’s founders were not. However, they can stand as exemplars for at least some aspect of life.

Take, for instance, an American founder with whom I have little in common: Thomas Jefferson. One of the most liberal of the Founders and a slave owner, I could easily see him as an ugly—albeit gifted—blight on my nation’s history. However, this kind of impious approach does little to help me. But if I look, I can find admirable aspects in this man’s character. To take just a single example, his writings on slavery are powerful. In letters, he refers to American slavery as a “moral depravity” and a “hideous blot.” Despite being a slave owner himself, he hoped that slavery would one day disappear from the American nation.

While these claims may seem unremarkable to readers today, we should realize how much humility it takes to admit, even in private correspondence, that one’s daily life is built around evil. When I look to Jefferson, I do well to remember this. If I know something is wrong with the way that I am living, I should not hide that contradiction. I should admit it, at least to my intimate friends and relations. Though doing so does not solve the problem, it can be a step towards changing my life. Jefferson himself never freed his slaves, and he is rightly chastised for this. However, his writings have helped generations to recognize the evil of slavery and other evils that ever lurk in my nation.

Though Livy tends not to spend a lot of time on explicit moralizing, it is clear that his writings are meant practically to inform his readers’ lives. His history of Rome provides examples of every kind of man, from the noblest to the most debased. He is blunt in the preface to his magnum opus, declaring that the Romans of his day—much like Westerners of ours—are in moral and political decline. But Livy affirms that he and his compatriots can still be ennobled by looking to the great deeds of their best forefathers and can learn from the mistakes of their worst ones. This is no less true today than it was when Livy wrote his great work. So maybe all these guys on TikTok have the right idea.