A few weeks ago, an acquaintance asked me what I had been reading lately. As it happened, I had recently become enchanted by a novel from the 1920s by an Austrian Jewish writer. The novel grapples with coming of age, loss, and the beauty and terror of nature. Despite being long overlooked by the Anglosphere, it has received a new translation, and The Guardian recently ran an article calling it “a dark parable of antisemitic terror.” Famous American conservative Whittaker Chambers produced a translation while he was still a socialist. Clearly, this is a novel that would be of interest to any reader. I did not provide such a description to my acquaintance, however, but merely told him the title, which elicited a bemused, almost condescending look.

The reason for this is that the novel I was reading was, in fact, Bambi, the story that nearly everyone knows in the form of the sweet little Disney cartoon from many moons ago.

My acquaintance was hardly unjustified in his response. Judging by the 1942 film, the story of Bambi is a relatively simple and childish tale. True, it famously deals with Bambi’s loss of his mother, but in general the movie leaves viewers old and young alike with the banal, sentimental, fuzzy feelings that has made the company that produced it an entertainment juggernaut. But these are not the feelings Salten’s original novel produces, nor is the novel particularly intended for children. How, then, did Disney’s image of Bambi become the predominant one? And how does this story and its reception shed light on our current Western culture?

Bambi’s author, Felix Salten, is a man worth knowing about. Born of Jewish parents in Pest, Hungary in 1869, Salten and his family moved to Vienna almost immediately after his birth. In Austria, as a young man, he decided he wanted to be a great writer. While he was a part of the ‘Young Vienna’ set (Jung-Wien) that boasted members such as Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Karl Kraus, and Stefan Zweig, Salten struggled to gain the kind of literary respect he desired.

Salten spent as much time as he could with the rest of the Young Vienna crowd, trying to learn all he could. During this time, he wrote prodigiously, publishing a book almost every year. He penned not just novels, but plays, short stories, essay collections, poetry, and even some travel writings.

It wasn’t until 1923, at the age of 54, that Salten published Bambi. The novel, in addition to expressing social commentary on the state of Austria and Europe, was the outgrowth of his lifelong love of nature. Ironically, given the novel’s depiction of the sport, the primary way that the author experienced the outdoors was hunting. Salten’s mode of hunting, however, was far from cruel. He was careful to hunt only what would be eaten, and in many ways hunting served as an excuse for him to spend time in the beauty of the outdoors.

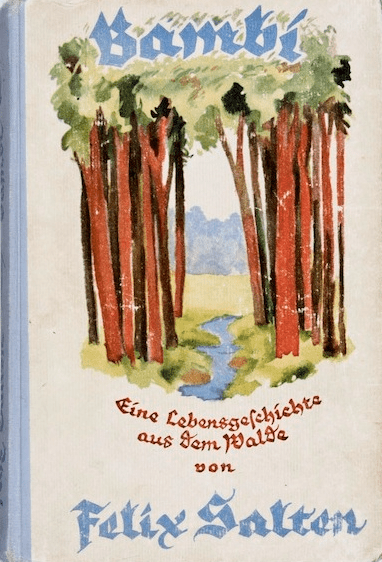

Bambi: Eine Lebensgeschichte aus dem Walde

By Felix Salten

Berlin: Ullstein Verlag, 1923

Bambi tells the story of a fawn who grows up to become a powerful stag. Beginning with his birth, the novel paints a series of portraits of life in the forest. These portraits are not just peaceful images, for they often depict the violence of life in the forest; not just violence from humans, but senseless violence perpetrated by animals onto their brothers and sisters. In the beginning, Bambi is a wide-eyed child who is entirely dependent on his mother’s guidance. In time, he learns about the hunter who prowls the forest and is taught how to avoid coming into contact with him. While his mother lives, Bambi finds out that there are great princes of the forest, powerful stags who live by their own wits. Bambi is stunned by the power and majesty of the princes.

Over time, Bambi’s mother begins to leave him more and more to his own devices, and he becomes comfortable roaming the forest alone. But one day he comes upon a hunter and is saved by his mother. This escape proves but temporary for his mother, however, as a large group of hunters come upon the forest at once, killing many of the animals, including his mother. This loss forces Bambi, under the tutelage of the oldest, sternest prince, to learn how to be alone.

The novel was a success in Europe. Five years after Salten published the book in German, Whittaker Chambers made an English translation. Surprisingly, given the power and moral complexity of Chambers’ later masterpiece, Witness, the translator failed to convey either the political import of the novel or even much of the artistic power. This more syrupy version of Bambi, however, was the one that caused the Walt Disney Company to purchase the film rights, which resulted in the movie that has been present in the Western public imagination for nearly eight decades. In addition to arguably cheating Salten out of a fortune, Disney turned his powerful (and at times subversive) novel into a film for children—not necessarily a bad film, but at root a morally simple one.

The original novel focused on the fear and violence of life in the forest, challenging readers to consider not only their relation to nature but also their relation to their fellow men. The film, on the other hand, had little in the way of moral and philosophical depth. The story was ‘Disneyfied’: simplified for mass consumption, with the hard edges of life smoothed over.

This Disneyfication is not simply something that happened in the past. It is a common tale today, and it is not just perpetrated by Disney, but by virtually all major corporations that produce Western media. So much of our entertainment begins as the careful labor of thoughtful artists engaging with profound questions and making works of beauty, but ultimately becomes an easily digestible commodity stripped of anything that could make it less ‘marketable.’

When this fact is brought up, some are tempted to blame it on hoi polloi being unwilling to show interest in meaningful art, but I think this is unfair. I have known too many people of little formal education and low income to be convinced by this. Oftentimes, the average man is more capable of serious moral reflection on art than our current elites. Sure, most people aren’t reading War and Peace or The Brothers Karamazov, but they appreciate films like It’s a Wonderful Life and The Godfather, films that are, at heart, moral tales that encourage viewers to reflect on their own lives.

I wonder if the problem comes not from the bottom but the top. The corporations that release films are just that: corporations. While they are, of course, staffed by many people with a love of art who wish to make meaningful works, everyone there is ultimately answerable to the bottom line. This necessarily causes people to be cautious. In addition, the sheer size of these companies, as well as the low number of productions and high budgets, means that it is more difficult for more serious films to be released. The average mainstream film costs around 65 million dollars. A lot rides on the success of any given film, so the likelihood that a visionary director or an inventive screenwriter will be able to make a meaningful work of art is quite low. This trend has been exacerbated in the past few years, as one of the main impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the movie industry has been to make it extremely difficult for smaller studios and less-established directors to get their films made and widely released.

Movies often end up Disneyfied: enjoyable, but ultimately bland and interchangeable blockbusters whose artistic merit has been sacrificed on the altar of marketability.

There is, however, one complicating factor that serves as a powerful objection to the tidy picture I have thus far offered: what about ‘wokeness?’ Films that serve as little more than morality plays for intersectional feminism and critical race theory often fair rather poorly in the box office (‘get woke, go broke,’ as the saying goes), and yet they keep being made. What, then, of marketability?

This is a tough question, and I do not think there is a simple answer. One thing to keep in mind is that, given contemporary political polarization, most decision-makers in Hollywood simply do not know people of good will who explicitly disagree in any meaningful way with contemporary progressive ideology. Now, they certainly know many people who admit to being ‘fiscally conservative and socially liberal,’ but this view (while objectionable to some in Hollywood) does not fundamentally challenge wokeness. ‘Social liberals’ are unlikely, for instance, to ever object to how depictions of ‘trans’ characters impact the mental health of teenagers and play a part in their permanent sterilization.

Thus, Hollywood decision-makers only know the woke (or at least fellow travelers), which means that they have no one to speak up when a story will not appeal to viewers. There are, of course, test screenings, but by the time a movie gets to that point, so many decisions have been made that, even if substantial re-shoots are filmed, its DNA is already poisoned by wokeness.

I think that many mainstream movies continue to be vehicles for wokeness because it is the only moral framework many people have. Many today have entirely lost the ability to speak in terms of ‘virtue’ and ‘vice,’ instead being comfortable only with language of ‘systemic’ injustices and hidden ‘phobias.’ Thus, even if a studio takes a financial hit for releasing a woke film, its staff can feel that they sacrificed to make a film that could do good in the world.

Now, I digress on the problem of contemporary art being either cheapened by Disneyfication or poisoned by wokeness for good reason. Salten’s Bambi is not a mere sentimental work, and, while the political bent probably isn’t what most would label ‘conservative,’ it is not a work of ideology. Instead, it presents readers with a tale that engages and challenges them.

Many conservatives say that they wish art would stop being so ‘political.’ I think this is a mistake. Art is and always has been political. Look to the dawn of Western narrative: if the Iliad were not political, Achilles would not have his concubine taken from him, and the entire story would never have happened. Man is a social animal, and art must then always engage with his nature as interconnected with others and dependent on them. Many works of art would be without a source of power and meaning if they were denuded of social and political implication. It would become nothing more than a Disneyfied shell that fails to challenge those who encounter it. Bambi stays far from political agnosticism. There are layers of political and social commentary for readers to unpack.

On the other hand, art cannot become a mere vehicle for partisan ideology. If Bambi were nothing more than a morality play about how perfect nature is and how evil men are, it would miss the mark. The novel seriously engages with the violence of nature and the presence of death in even the most bucolic of scenes. It never gives readers a tidy package promising to fix their political problems. After finishing the novel, whether in 1923 or 2022, readers are left with questions about how we ought to live.

The new English edition of Bambi is a triumph. With clear translation by Jack Zipes and beautiful illustrations by Alenka Sottler, the edition is simply a joy to read. The translator provides an excellent introduction to the volume (though I would advise waiting until after completing the book to read it if you prefer not to have even classic literature ‘spoiled’).

Though the novel has often been overlooked in the Anglosphere, it is a rewarding read. It reminds readers that seemingly simple stories can be intellectually rewarding, and its political allegories (unlike so many) still have meaning for us decades after its initial publication.