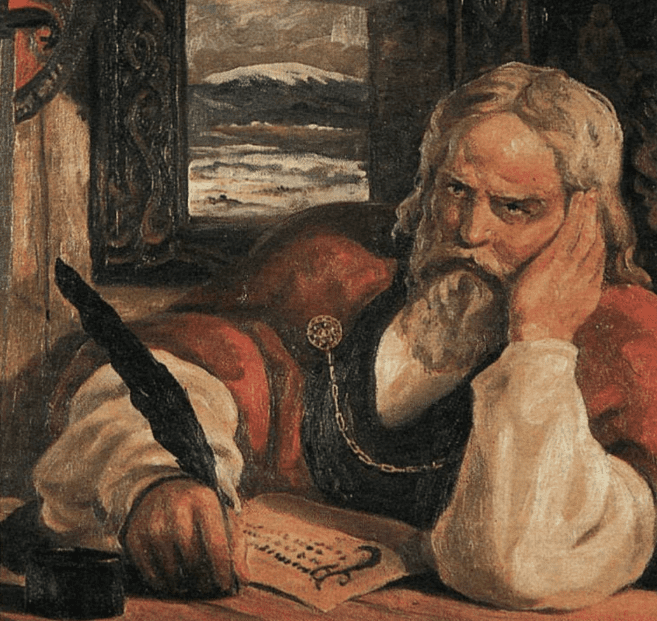

“The Sacrifice of Odin” (1895), an illustration by Lorentz Frölich(1820-1908) for Den ældre Eddas Gudesange by Karl Gjellerup.

We live in an odd era. This oddness takes many forms, but one of the most significant is how alienated we are from traditional rituals, folkways, and religious practices.

Throughout human history, human life in every culture has been punctuated by sacred times that involved specific practices. Whether annual celebrations like Christmas, Easter, and Carnival or daily practices like saying the Angelus, the Christian West has been just as attuned to man’s need for regular ritual as any other civilization. Yet in recent times, many developed nations have worked to jettison these practices, whether through downplaying religious holidays, discouraging public displays of heritage, or idealizing efficiency and convenience over ritual and stability.

Attached to these traditional practices are the stories that underlie them. These stories may be purely mythical, verifiably historical, or something else altogether. In the West, such stories are generally rooted in the Biblical narratives or stories from the lives of saints. However, in the name of secularism and inclusivity, contemporary Western educational methods tend to shy away from lengthy engagement with Christianity, instead preferring to focus on curricula made up of some combination of scientific and multicultural/gender studies.

This disconnection from the religious practices and narratives that animated the West for more than a millennium is harmful for myriad reasons, but I will mention just two. The first is that this alienation means that young people have genuine difficulty understanding and appreciating the gift that is Western civilization. The second is, of course, that their imaginations and spiritual lives are necessarily less rich, less open to wonder, and perhaps less open to God.

What, then, is my proposal to fix this problem? Obviously, teachers and schools throughout the West are unlikely to begin forming their students through deep immersion in Christian literature simply because I say so. Yet I think there may be a compromise. And that compromise begins with some old myths.

In his well-known memoir, Surprised by Joy, the novelist and Christian apologist C. S. Lewis paints a vivid picture of the people, places, and books that brought him from atheism to Christianity. As an adolescent, he fell in love with the tales of the Norse gods. Whether in their modern forms presented by Wagner and Longfellow or their ancient forms in the poetry and prose of the Icelanders, Lewis was enchanted by their stark beauty.

Norse mythology, unlike the Sacred Scriptures, does not present readers with loving and merciful divinities. The Norse gods are violent boozers, many of whom seem to spend most of their time playing practical jokes and fighting giants. And yet there is a great power to the tales. For instance, the Prose Edda spends pages painting a picture of the Norse cosmos, a cosmos with much fuel for imagination. This cosmos is made up of “nine realms,” each one a world unto itself but connected to the others through the singular, unifying “world tree,” Yggdrasil. Images like those of Ingri and Edgar d’Aulaire give a sense of the wonder this cosmos inspired in the mind of the young C.S. Lewis.

In addition to the Norse cosmos itself, there are the stories of what goes on there. Most of us have at least heard the names of a few Norse gods (at least Thor, Loki, and Odin), but we generally don’t know much about them. Amusingly, since the Prose Edda was compiled by a Christian, there is a tendency to share stories that involve Thor ending up in embarrassing situations. (Perhaps the most ridiculous is when the mighty god Thor is forced to cross-dress and pretend to be excited to marry a hideously ugly enemy of the gods before attacking him.) While these stories are funny, there are more poignant stories too, and it is these that have the power to instill great wonder, tales like those of the creation of all things, of the binding of Loki, and of Ragnarök. These stories paint images of a world of power and beauty that readers long to enter.

Unfortunately, we cannot fully enter this world. Our knowledge of the stories of Norse mythology is not as extensive as our knowledge of some other culture’s myths. For example, whereas for the Greeks and Romans we have numerous complete sources of tales from mythology, we cannot even know how much Norse mythology we have lost. But for Lewis, the incompleteness was part of the romantic appeal of Norse myth. On encountering the Norse myths, we readers are struck with a powerful sense of encountering, not just a strange and compelling world, but a lost world, one that can never be fully explored or understood.

For the young Lewis, the Norse myths had a distinctive character that he called “northernness.” He describes the experience of encountering Wagner’s Siegfried and the Twilight of the Gods:

Pure ‘Northernness’ engulfed me: a vision of huge, clear spaces hanging above the Atlantic in the endless twilight of Northern summer, remoteness, severity … and almost at the same moment I knew that I had met this before, long, long ago [in other works]. And with that plunge back into my own past there arose at once, almost like heartbreak, the memory of Joy itself, the knowledge that I had once had what I had now lacked for years, that I was returning at last from exile and desert lands to my own country; and the distance of the Twilight of the Gods and the distance of my own past Joy, both unattainable, flowed together into a single, unendurable sense of desire and loss, which suddenly became one with the loss of the whole experience, which, as I now stared round that dusty schoolroom like a man recovering from unconsciousness, had already vanished, had eluded me at the very moment when I could first say It is. And at once I knew (with fatal knowledge) that to ‘have it again’ was the supreme and only important object of desire.

Little did the young Lewis know, however, that the chase after this “northernness” and heart-breaking “joy” would ultimately bring him, not to Scandinavia or aestheticism, but to God.

One of the Prose Edda’s idiosyncrasies is its opening section, which attempts to connect the Greek pantheon with the story of creation told in the Book of Genesis. As noted earlier, Snorri Sturluson, the work’s author, was a Christian, but he was also a lover of traditional poetry. Like St. Augustine, Tertullian, and so many Christians before him, Snorri had to wrestle with the place pagan learning might have in the Christian life. His attempted solution was to present readers with his theory of how these myths came about.

The work begins with a very brief account of God’s creation of the world and Adam and Eve. Snorri tells readers that, after Adam and Eve fell and sin entered the world, human beings still reasoned about the divine despite not being in union with Him. Thus, in the generations after a prophet named Odin became a king, people in Northern lands began telling stories about gods with names like Odin and Baldr (Odin’s Son).

With this in the background, Snorri then dives into the pagan Norsemen’s own tales, soon describing their creation myth. This myth, however, differs starkly from the account of creation Snorri gave first. Whereas the Christian story told of a Triune God who speaks the world into being out of love, the Norsemen tell a story seeped in violence.

A 1933 painting of Snorri Sturluson (1179-1241), a 13th-century Icelandic poet and politician, by Haukur Stefánsson.

The work begins with a very brief account of God’s creation of the world and Adam and Eve. Snorri tells readers that, after Adam and Eve fell and sin entered the world, human beings still reasoned about the divine despite not being in union with Him. Thus, in the generations after a prophet named Odin became a king, people in Northern lands began telling stories about gods with names like Odin and Baldr (Odin’s Son).

With this in the background, Snorri then dives into the pagan Norsemen’s own tales, soon describing their creation myth. This myth, however, differs starkly from the account of creation Snorri gave first. Whereas the Christian story told of a Triune God who speaks the world into being out of love, the Norsemen tell a story seeped in violence.

In the beginning was the yawning abyss, Ginnungagap. Within Ginnungagap, ice formed (hardly a surprising speculation for men from such a cold and unforgiving land), and when it was met with a warm wind (or perhaps fire), life began. This first life was a ‘frost giant’ named Ymir. In time, more beings came to exist, and this is when the violence erupts. Ymir’s descendants, including Odin, feared him. Thus, they slaughtered Ymir and fashioned the world from his corpse. The world as man knows it, then, is the result of the first murder.

This bloody streak runs through the Prose Edda. This is perhaps never more explicit than in its account of the human afterlife. The closest thing to a Paradise is Valhalla, where great warriors are brought after dying in battle. (Despite a popular misconception about women who died in childbirth having seats in Valhalla, it is only warriors who are brought there.) Odin made Valhalla for a single purpose: so that the warriors could fight and die for Odin during Ragnarök, the ultimate cataclysmic event where Odin, Thor, and many of the other gods will be killed. Thus, ‘Heaven’ is only for strong and mighty men, and it is nothing but a temporary respite before ultimate destruction in battle. Man has no hope of final happiness, and the gods are just as bloodthirsty as Viking marauders. How, then, could these stories have brought a man like C.S. Lewis closer to belief in Christ?

To answer this question, let us turn to one of Lewis’s more academic works, the address he gave when he was awarded the Chair of Mediaeval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge University in 1954, “De Descriptione Temporum” (A Description of the Times). Given long after his conversion, in this lecture the professor attempted to explain what purpose an orthodox Christian could possibly have for the modern, secular university. The short work is a masterpiece from beginning to end. For our purposes, however, what is helpful is his view of the relationship between paganism and Christianity on the one hand and modernism on the other. As he puts it, “Christians and Pagans had much more in common with each other than either has with a post-Christian. The gap between those who worship different gods is not so wide as that between those who worship and those who do not.”

While it is easy as either a Christian or a “post-Christian” to look down on the ancient pagans with feelings of superiority, in reality they were trying to find their way in a fallen world with very little help. While they lacked a true understanding of God and the conveniences of modern technology, the originators of these myths had an honest awareness of their ultimate powerlessness in the world, something we could learn from. The contemporary world tells us that we are masters of the universe who can make the world bend to our will. Yet, nature is having the last laugh. Whether you worry about COVID-19 (which likely came from tampering human hubris) or the breakdown of marriage across the West that has come from the introduction of contraception and no-fault-divorce, it is becoming increasingly clear that human beings need the humility to accept their place in the world.

When we reflect on this contemporary instability, it becomes easier to understand Lewis’ position. Lewis believed that Western culture was not only detached from Christianity, but also that it was increasingly becoming detached from nature itself. In this process, our reasoning faculties have become perverted to the point that they struggle to understand what they ought to know by nature. (Widespread belief in ‘transgenderism’ is a prime example of this kind of malformed reason today.) But faith builds on reason, so Lewis argued that Christian faith was increasingly difficult for modern man because of the simple fact that we are disconnected from our nature and have increasingly malformed faculties of reason. Thus, simple wide scale reversion to Christianity is extremely improbable. What is needed, Lewis argues, is for the West to reconnect with human nature, fallen though it is, to eventually reconnect with the divine. To put it simply: the West must become more pagan before it can become more Christian.

There is one striking parallel between Norse mythology and the Christian story that is deserving of our attention. In Norse mythology, Odin had such a great desire for knowledge that he sacrificed his eye, threw himself on his spear, and hung himself dead on Yggdrasil, the world tree, for nine days in order to gain true wisdom and prophetic sight. Reading the Prose Edda’s description of these events, it is impossible not to reflect on Christ’s sacrifice on the wood of the Cross. While in previous centuries some scholars argued that tales like these were influenced by the Christian Scriptures, authorities today generally reject most of these claims. Regardless of the exact sources of this myth, it is fruitful to consider how it serves as a mirror to (or rather anticipation of) the central Christian story of the Crucifixion.

Odin and Christ both took on great pain, bearing it in ways that we are meant not only to look up to but even imitate. However, while Christ acted out of humility “not judging equality with God something to be grasped,” Odin was motivated by desire for gain. Odin wished to attain wisdom to prevent his downfall (a downfall that was inevitable and brought on by his ruthless treatment of Loki). Christ, on the other hand, freely chose to take on the weakness of human flesh, not out of any lack, but purely to show forth divine love and ransom mankind from sin and death.

As the then atheistic C.S. Lewis aged, he made friends who shared his affection for myth, most famously the Catholic J.R.R. Tolkien. While Lewis appreciated the mythic qualities of the New Testament, and he accepted that much of what was recounted there was historically correct, he “couldn’t see . . . how the life and death of Someone Else (whoever he was) 2000 years ago could help us here and now—except in so far as his example helped us,” as he put it in Surprised by Joy. Facts were facts, myths were myths, and ne’er the twain shall meet. Myths were nothing more than “lies.”

But Tolkien challenged this view, eventually convincing Lewis he had been wrong. All traditional mythology contains some piece of truth. These are generally not truths that can be articulated within a purely materialistic framework, and yet they somehow all groped in the dark towards the same unified reality. But what if there were one myth that was not crafted by the human mind? What if a single myth was given to us by God? The Bible is such a myth. But it is not a myth given merely in words, but through the very history of the world. All other myths stand to Scripture as a wondering question stands to its answer.

Reading the Norse myths has many benefits: it entertains, edifies, and spurs on reflection. But perhaps the greatest benefit is how it feeds our wonder, a wonder that finds its ultimate fulfillment in the Triune God. Far too often we become jaded, whether by the technological wonders that surround us or by the free offer of God’s grace in Christianity. But these myths force us to separate ourselves from our daily lives and enter the hearts and minds of a people very different from us, and yet a people whose hearts had the same anxieties and fundamental longings as ours. Whether you, like the young C.S. Lewis, have no belief in God or, like Snorri Sturluson, are a Christian who wishes to experience the beauty and questions that have been bequeathed to you, do yourself a favor and take a look at the Prose Edda. A little wonder is never a bad thing.

This essay is the third in the monthly series “Forgotten Classics.”