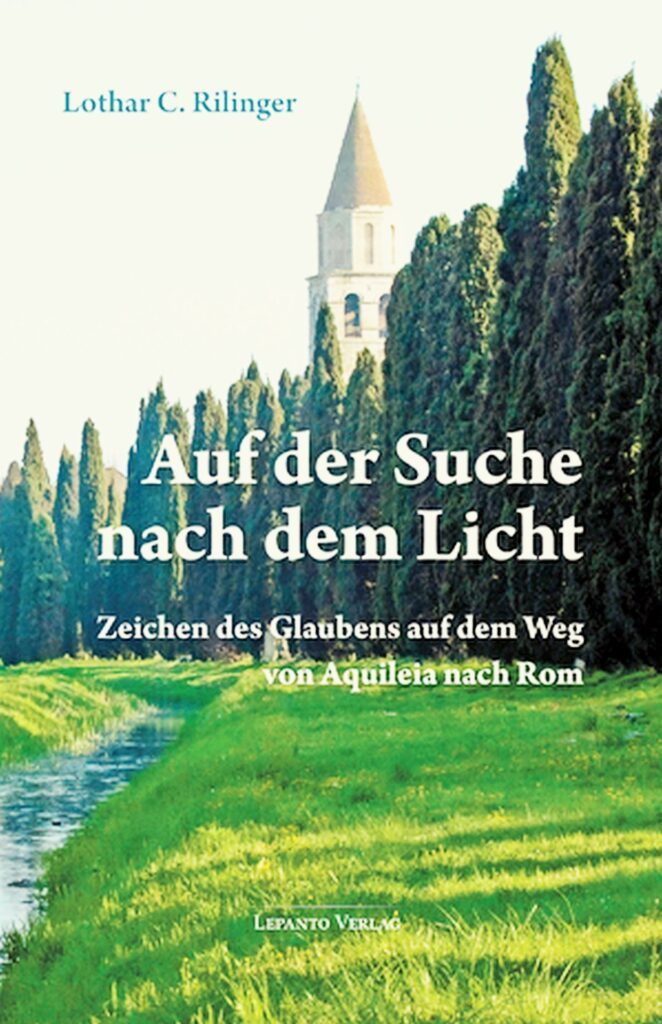

Anyone in search of the light, operating in an occidental context, cannot avoid looking to Rome. Lothar C. Rilinger, the well-known, decidedly Catholic publicist, does the same. But his new work Auf der Suche nach dem Licht – Zeichen des Glaubens auf dem Weg von Aquileja nach Rom (In Search of the Light – Signs of Faith on the Road from Aquileia to Rome) does not begin in the Eternal City. No, it is about a search, and even more about an approach. Just as the author promises in the title of this book, it is a journey into the light—and a double journey at that!

Rilinger first takes the reader into the southern Alpine atmosphere, in which the mythical Arcadia reveals itself layer by layer. It is an atmosphere that magically envelops us northern Alpines once we have crossed the main Alpine ridge. This journey to the light should lead us to the place where the eternal light of the Occident literally burns—if it is extinguished, the light of culture and faith is extinguished on the entire Occidental continent. This transcendental aspect of the book seems so simple, so clear.

Let’s start with the delicate Arcadian charm of the southern slopes of the Alps. Here we experience a travelogue of literary quality. We walk along an anabasis from Aquileia—which sank into insignificance in late antiquity—up to the throne of Peter, to Roma æterna. What does this have to do with the West itself? Here we are at the point where we need to recognise the second level of this work, which is what makes it a double travelogue. For Rilinger also succeeds in setting in motion an inner journey: a journey of the soul to the supra-temporal, the cultural, the spiritual Rome within us.

Cividale del Friuli is not on the usual, major travel routes. But this is exactly where Rilinger begins his journey to Rome, because a jewel of Lombard art can be found here. The formal language of late antiquity, already used in the early Middle Ages, is fascinating in itself, and is put into context with thoughtful, far-sighted prose. It is not far from here to Udine. This city, much larger, is always in the tourist slipstream, but not really in the south, and not even by the sea. Rilinger describes why we should stop anyway, and why this is an important stop if you want to reach Rome with knowledge.

A concentration on the essentials—this is how the broad chapter on Venice could be characterised. However, the author restricts himself to two narrowly defined places, from which he shines a light into intellectual and church history. He does this very purposefully, because he knows exactly what he wants to emphasise and show. Everyone knows St. Mark’s Square and the Doge’s Palace. In contrast, Rilinger begins with the church of Santa Giorgio Maggiore, and again he lets his thoughts describe a wide circle. The reading becomes more and more rewarding—here, however, we can only quote the conviction that “true greatness, which can only be achieved in the glorification of God,” can be found in Venice. The author then encounters Titian’s genius in the church of San Salvatore, and he knows how to honour it. Worthwhile thoughts on the relationship between church and state conclude this chapter.

The chapter on Florence is layered like a dome. From the exterior to the interior, upwards, towards the sky—and back again—Rilinger describes this city as a total work of art. The reader senses that someone is writing here who has been moved and who has understood. Florence is the resting place on the way to the light, culture, and the honour of God. Santa Croce, Giotto, Dante—these are powerful keywords. The themes linked to them deal with turning away, repentance, and a return in the biblical sense, extrapolated above all in relation to the papacy. In this way, the author also directs the reader’s gaze from here to Rome. But in the centre of the chapter, at its height so to speak, the dome of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore is described, Brunelleschi’s unrivalled masterpiece. This chapter thus becomes a work of art in itself.

Rilinger now takes his readers on a journey through Tuscany and Umbria. It is well worth reading, as the comments made so far suggest. And then, at the gates of the Eternal City, comes the collection of pictures, highly informative and well assembled. It comes a little late, but it is the fanfare before the pilgrim enters the Eternal City. However, this is not a problem because, after all, a book is there to be leafed through.

Rome then—Caput Mundi. Here the pilgrim—for the reader has long since come to understand himself as such—has arrived at his destination. Here, standing equally in the light, the author now elaborates on some selected ecclesiastical themes. The Order of Malta and its works are included, as is Pope Pius XII (whose canonisation is hoped for in some quarters). An important chapter is dedicated to Benedict XVI, the future Doctor of the Church. From Rome, Rilinger directs the reader’s gaze to Lourdes and Bethlehem, albeit without spiritually leaving the city. Rilinger takes the reader by the hand and shows him his panopticon of faith, so that the city and the world open up to him. Only those to whom Roma aeterna has revealed its secrets will understand Europe. The author knows this, the publisher knows this, and here every reader learns this, too.

As far as the external form is concerned, the Lepanto publishing house likes to pile things deep. As with previous publications by this very thoughtful and focussed publishing house, the wish arises that this work should have appeared in a hardback form, bound in bookbinding cloth, with a ribbon marker and dust jacket, that would have lasted for centuries. However, in view of this marvellous presentation, which captures the breadth and depth of the Occident, we are once again—nolens volens—in favour of a paperback edition. For page after page of this dense, rich, far-sighted, literally groundbreaking book is well worth reading and savouring.