While in his heyday, Dutch painter Frans Hals enjoyed renown as his country’s preeminent topographer of the human face. Never of the frugal sort, he faced bitter destitution near the end of his twilight years.

A pension from his adopted city of Haarlem—a rarity during Holland’s Golden Age—nonetheless reveals the esteem in which he was held. It was to sustain Hals for another four years until his death in 1666 at the ripe old age of about 84. An even greater honor was bestowed when the city decided to have Hals—who could not afford a grave—interred in its grand St. Bavo Church; today, one can find him there, commemorative plaque and all, in the choir section.

Centuries later, London’s National Gallery brings tribute of its own to the Dutch Master—who since his death never did quite manage to step out of the shadows cast by Vermeer and Rembrandt—by putting on show 51 of his paintings, some of which have rarely been seen on public display.

Though celebrated in their time for their virtuoso, loose brushwork, rich color palettes, and the dynamic, personality-revealing poses of their sitters, Hals’ paintings quickly fell out of fashion after his death. If it wasn’t for the influential French art critic Théophile Thor, the period of waiting for the resurrection of Hals’ art might have been even longer. Almost two centuries after the Dutch masters’ passing, it was Thor who noted his “extremely vigorous handling of the brush,” which he likened to a fencer wielding his saber.

No preliminary drawings by Hals’ hand have ever been found, which only added to the posthumous admiration he garnered. Instead, he worked largely alla prima, i.e., he applied paint onto previous layers of still-wet paint in a single session. For this he was regarded as one of the most important forerunners of the loose manner of painting which was coming in vogue. In that heady era, the Parisian avant-garde embraced Hals as one of their own, as French art made its transition from realism to impressionism. As Hals grew older, he even started leaving out that layering process entirely, which made the impressionists love him even more.

When Édouard Manet, one of the first 19th-century artists to depict modern life and somewhat of an elder statesman to the impressionists, joined in and gave Hals’ work his nod of approval, Hals’ place in art history was solidified. Among the impressionists’ progeny, Hals found favor with none other than Vincent Van Gogh himself. Van Gogh’s words have the distinction of opening “The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Frans Hals,” expertly curated by Bart Cornelis. A plaque reproducing a quote from a 1888 letter to Van Gogh’s colleague Émile Bernard reads:

Frans Hals painted portraits; Nothing nothing nothing but that. But it is worth as much as Dante’s Paradise and the Michelangelos and the Raphaels and even the [ancient] Greeks.

A bold promise to start off with to be sure, but luckily one the exhibition—the first major Frans Hals exhibition in 30 years—makes good on. 51 paintings (in all, some 220 paintings have been authenticated as being Hals’) can be seen there, many of which from private collections.

The Dutch Golden Age saw the emergence of a new merchant class, who valued portraits of themselves as symbols of high social status—one for which they would pay handsomely. This well-to-do bourgeoisie, or so it must have believed, was the vanguard of a new kind of civilization, destined for greatness. Vanity would demand that the countenances of such a vanguard be captured for posterity.

Consequently, the demand for such paintings rose, and competition between painters over the most lucrative commissions became more fierce in turn. Hals’ family, along with nearly half of their fellow citizens, fled their native Antwerp in the wake of Spain’s victory over it. Even though he was too young to have soaked up Antwerp’s art before his family’s exodus, Hals’ inborn Flemishness seemed to have given him the edge over his competitors.

In contrast to their Dutch counterparts, in the 17th century Flemish painters, such as Peter Paul Rubens, were steeped in the Baroque, and laid great emphasis on movement, color, and sensuality. Art historians suspect Rubens might have met Hals during a business trip to Haarlem in 1612, though this is unproven. The latter, however, did visit Antwerp four years later, where he is sure to have seen Rubens’ work, if not paid the man himself a visit.

While technically proficient, many Dutch painters of Hals’ time produced rather stilted work. In contrast, Hals’ art possessed an uncannily lifelike quality.

One of Hals’ earliest attempts at commissioned portraiture was in the genre of pendants, i.e., two portraits related thematically and displayed in close proximity. Hals’ clients, usually men of means, often liked to see themselves immortalized with their wives. As was the case with many such pairs, over time they were broken up, never to be seen together again. Two of these, among which Portraits of Pieter Dircksz Tjarck and Marie Larp (1635), the exhibition reunites at last.

While married men were usually depicted in monochromatic black dress—with all the formality that such dress denotes—social convention saw no issue with bachelors wrapping themselves in more gaudy attire. Hals’ most famous painting, The Laughing Cavalier (1624)—a rare loan from The Wallace Collection, whose London premises it has not left since 1900—might be characterized as a depiction of unashamed, high-level peacocking. With his coiffed mustache, frilly lace collar and exquisitely embroidered silken sleeves, its proud sitter seems to be on the verge of exclaiming: “Get a load of me, ladies! Don’t I look grand?”

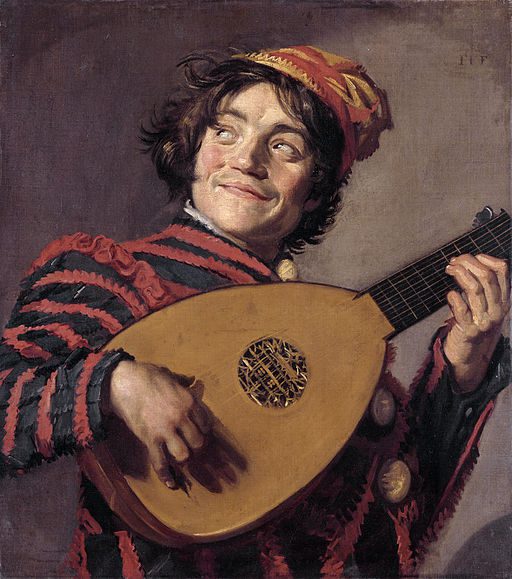

In his genre paintings showing scenes of everyday life especially, Hals’ great skill in depicting the human smile comes to the fore. He was one of the first to do so, since artists usually avoided them—for in less skilful hands, a smile would often turn into an unappealing grimace. But in Hals’ works, whether depicting the disarming smile of a lute player, gypsy woman, or a fisherman’s boy, an infectious joie de vivre is conjured up.

Hals’ services were also enlisted for group portraits. Highly popular in the 17th-century Dutch Republic, these were often commissioned by civic organizations such as guilds, militias, and charities. While the most famous militia painting is undoubtedly Rembrandt’s The Night Watch (1642), Hals’ Banquet of the Officers of the St. George Civic Guard (1627), never before loaned out by the Frans Hals Museum, is nothing to sniff at; the viewer feels as if he has just stumbled upon the company of men, each depicted in his unique individuality, in their merry-making.

For Hals’ mentor, Karel van Mander, portraiture was inferior (a “sideroad of art,” he wrote in his 1604 treatise SchilderBoeck) to the depiction of human figures in biblical or mythological stories which, so he argued, kept audiences mindful of more lofty things. Likely to van Mander’s chagrin, religious art in places of worship was often eschewed in the Calvinist Dutch Republic, and, with no Rome to act as wealthy patron, there was even less incentive for painters to try their hand at this particular genre.

In the aforementioned letter to his friend, Van Gogh, though he esteemed Hals’ portraits as art, appeared to share Mander’s disappointment, writing: “Never did he [Hals] paint Christs, Annunciations to shepherds, angels or crucifixions and resurrections; never did he paint voluptuous and bestial naked women.”

Putting the lie to British art historian E.H. Gombrich’ assertion that Hals was but a proto-photographer (“[he] gives us something like a convincing snapshot, [whereas] Rembrandt always seems to show us the whole person”), the unique sense that one gets upon concluding the tour is that Hals is possessed of a keen psychological insight, which consistently informed his work throughout his career.

It is sobering that, although Hals was the first of the three masters associated with the Dutch Golden Age, his fame comes nowhere near to that of Vermeer or Rembrandt. The National Gallery’s once-in-a-lifetime exhibition offers Hals’ best chance at winning the art-loving public’s affections; his more illustrious peers have earned a break from the limelight.

“The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Frans Hals” at London’s National Gallery is open for visitors until January 21, 2024. It will then continue at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum from February 16 to June 9, 2024.