In the early 1990s, the avant-garde darling and Catholic convert Lars von Trier was invited to make a show for Danish television. Having received permission to film at Copenhagen’s Rigshospitaliet (“Hospital of the Realm”), where his own children were born, Trier chose to make The Kingdom, a hilarious and terrifying critique of turn-of-the-millennium scientism and materialism, in the style of something David Lynch might do if asked to direct E.R. with the side characters from the X-Files. In The Kingdom, something is rotten in modern Denmark, and its source is spiritual.

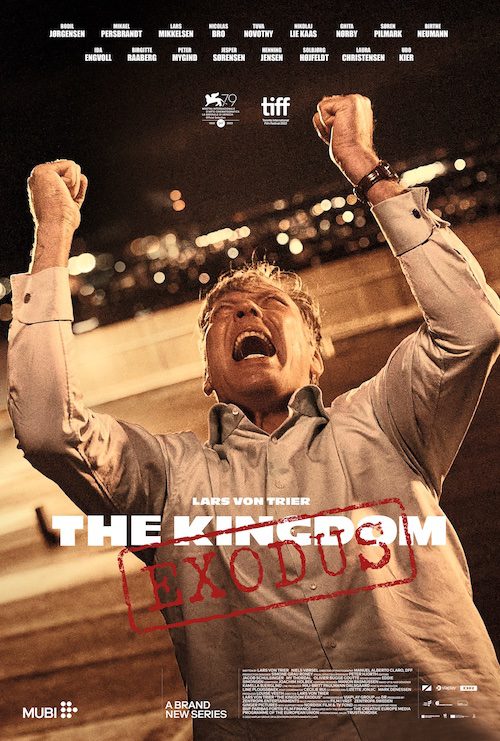

The first four episodes of the series aired in 1994 to widespread acclaim, with four more following in 1997, making Trier a household name in his own country and broadening his arthouse appeal elsewhere. A quarter century and over a dozen feature films later, Trier has recently returned to finish the tale in five episodes collected as The Kingdom: Exodus, which premiered on Danmarks Radio in October 2022 and worldwide on the streaming service Mubi in December 2022. The long-anticipated finale is weird and poignant, making fun of and shining light on the dark corners of the international pharmaceutical and surgical dominion the world now mostly regards as sacrosanct. All three seasons are must-watch.

Each of the thirteen episodes of The Kingdom begins with a prologue, describing how the towering medical center at the heart of Copenhagen is built on an ancient lowland where “the bleach men” once washed their linens in the swamp. The new kingdom sits precariously on the shifting ground of the past, as the narrator explains:

Perhaps the arrogance has become too great—just as the consistent denial of the spiritual—for it appears, the chill and damp have returned. Small marks of fatigue are emerging—on the otherwise sturdy and modern buildings.

The old world is not dead, and disturbing phenomena out of the past begin to re-emerge on the very spot where modern man thinks he stands in triumph over nature itself.

Each episode finishes with a personal appearance and commentary from Trier, who signs off with a mischievous grin, accompanied by the warning, “be prepared to take the good with the evil.” At the end of the third episode, he describes his project more fully: “In the shadow of the eccentric, the charming, and the zany, terror lurks. Maybe that’s the background against which man’s wickedness is clearest.”

In Season One, Trier and co-writers Niels Vørsel and Tómas Gislason explore the oddities of hospital life through the character of Mrs. Drusse, a spiritualist snoop who presses her son, Bulder, a hospital orderly, into helping her find ghosts. At the same time, the hospital receives a new neurosurgical professor, the bumbling Stig Helmer (Ernst-Hugo Järegård, previously in Trier’s film Europa), whose pride in his Swedish identity and his disdain for Denmark are recurring comedic tropes throughout the series. Helmer and the rest of the senior medical staff possess no bedside manner and are easily distracted by personal trivialities, concerning themselves with patients only for the sake of scientific advancement. The Danish doctors meet at night to perform Masonic rituals, with one member telling Helmer, “the lodge oath overrides everything else,” including, critically, the Hippocratic oath. Viewers may think here of the new norm of doctors’ complicity in contemporary medical atrocities such as abortion, euthanasia, and sex reassignment surgeries.

In the background of the doctors’ malice and incompetence is Mona, a girl whose botched brain surgery has made her spiritually attuned to the evil emerging in the building. In the hospital kitchen there is a chorus of two dishwashers with Down Syndrome, one of whom pronounces judgment on the hospital’s dirty secrets, “the archives seem so peaceful, yet all the pain is gathered there.” And then there is Judith, a doctor whose inexplicable pregnancy progresses unnaturally quickly, culminating in the birth of “Little Brother” (Udo Kier, another Trier favorite) in the season’s gruesome finale.

In Season Two, tension grows between the wayward doctors’ methods and the supernatural rebellion that they can no longer dismiss. At the start of the fifth episode, one of the dishwashers declares, “Everything is decaying, and nobody notices.” Later, an old doctor addresses his fellow lodge members with a warning about the Kingdom’s “infection,” which he attributes to alternative remedies threatening the conventional methods that have made physicians rich and respectable. Even chamomile tea is suspect! As proof of the doctors’ insane commitment to the exclusive form of medical progress they have embraced, a medical professor named Dr. Bondo transplants a liver with a rare cancer into his own body to test its effects.

The amused and horrified viewer of the first two seasons of The Kingdom may notice how Trier’s depiction of the medical establishment’s paranoia is only barely a caricature. (Today’s viewers may call to mind the recent worldwide controversies during the COVID pandemic related to even asking questions about possible risks or effectiveness of vaccines, but also the bizarre unwillingness of some members of the medical establishment to allow other therapies. Less well known is the Food and Drug Administration’s recent move to reclassify centuries-old, European homeopathic medicines to make them more difficult to bring to the American market.)

But one also wonders whether there is any realistic way back to a holistic union of human effort and immutable spiritual laws. Can we just ‘RETVRN,’ as they say? Perhaps not. In his monologue the end of the sixth episode, Trier explains, “To understand our world, the ‘inner’ and the ‘outer’—we must adopt a cynical view: Back and forth are just as far.” In this way, one of the most poignant lines in the series comes in the eighth episode when the female dishwasher wonders, “Maybe the evil is me.” The male dishwasher agrees, echoing Solzhenitsyn, “Yes, maybe it’s us. The uncertainty is the beauty of it.”

In the final episode of the second season—appropriately named “Pandaemonium,” Judith’s unnatural child prepares for his inevitable death, asking to be baptized with the name Frederik, after the crown prince—a tribute to a now-powerless earthly kingdom, whose history nonetheless represents a tenuous connection to the Kingdom of Heaven. In contrast, as the hospital walls crumble, the deranged Dr. Hook responds with nihilistic rage, declaring, “We keep a lot of people alive by machinery,” and threatens to cut the power to the hospital. The view is bleak: perhaps there are few options to the technocratic paradigm than either lying down on the deathbed of monarchy and Christianity or turning off the lights of civilization and running away. In any case, Mrs. Drusse speaks for a great many people concerned about the state of the world today when she concludes, “Someone must be worshiping the devil here.” Perhaps simply naming the Enemy is a start.

The third season, The Kingdom: Exodus, adds a new narrative twist: The characters in this drama are aware that there has been a cult television show about previous events, and the hospital has become a tourist destination for fans. The facility looks much the same, and some of the old cast is still around, including Judith, an even weirder Dr. Hook, and “Little Brother,” now calling himself “Big Brother,” who lives again as a giant in the bowels of the hospital. A chronic sleepwalker named Karen, an admirer of Mrs. Drusse, checks herself into the hospital and receives aid from a new orderly (nicknamed “Bulder” after the previous one), who together continue the hunt for signs of dark spiritual power. There is a new chorus of dishwashers in the basement, with one of them now being a robot.

Most significantly, Exodus features a new Dr. Stig Helmer (Mikael Persbrandt), son of the original, who seeks to redeem his disgraced predecessor’s name. Like his father, he descends on Denmark’s premier hospital with prejudice and buffoonery, but in a moment of clarity in the final episode he reflects coldly, “I belong to the evil side now, it seems.” Nicknamed “Halfmer”—i.e., he is half the man his idiotic father was—he haughtily explains to his Danish colleagues that the hospital staff’s level of diversity is “beneath contempt,” and he institutes a genderless record keeping system that results in people receiving the wrong surgeries. Despite his efforts to follow the latest best practices on ‘consent’ in social settings, a female doctor charges him with multiple harassment lawsuits. All the while, the demonic Grand Duc (Willem Defoe) prepares the way for the final arrival of his Master, without anyone much noticing.

A recurring aspect of the latest series is that the hospital is hosting a pain conference, presided over by the neurotic Dr. Pontopidan, who speaks in biblical turns of phrases and is eager to avoid confrontation. The conference, which offers guests large swag boxes hilariously labelled “free shit,” indicates that after two and a half decades of medical research since viewers were last inside the hospital, the greatest advance is just that they are now better at numbing patients. Whereas when we last left The Kingdom in 1997, spiritual chaos reigned, now even the physical torment that reveals man’s stature and can sometimes spur his transformation has been neutralized. “Pain is your friend,” promises the official slogan of the fictional Rigshospitaliet today. There is even an opium den where emeriti physicians live out their retirement years.

In the closing monologue of the penultimate episode, Trier speaks in contradictions about the current culture of his continent saying, “Following the shameful European political trends, I’ll swing to the right, while I advise any viewer still awake against doing the same.” The show is clearly an indictment of the aimless Left-Wing trajectory that cannot help but invite the forces of darkness into the driver’s seat. It is humorously anti-woke. And yet, Trier is a creature of the modern world, and is no throwback to the ancient ‘bleach men’ of the past.

He treads a unique path for himself—a way paved by his own rebellious expression of Catholicism that grew out of a strange childhood in a nudist-atheist-socialist Jewish family, and complicated as an adult when he found out the man he had known as his father was not. And even though Trier once gave a controversial answer to a question at the Cannes Film Festival expressing fascination with Nazis, he shows no evidence of participation in or sympathy with even conservative, let alone Fascist, politics at all. He is reticent, therefore, to commend reactionary ideology above the mainstream secular values that his show critiques. The robotic dishwasher may therefore speak for Trier when it says, “Doubt is better than nothing.”

What Trier is unashamed to imply, however, is that the problems facing Denmark, Europe, and the world beyond may be tangentially political or technological, but they are certainly spiritual at their core. As Joseph Ratzinger wrote in A Turning Point for Europe in 1991, “It is characteristic that one now speaks simply of the ‘kingdom’—without mentioning God—and that this is understood now as the ideal human society.” But man is deluded, turning his ‘Exodus’ from the bondage of religious superstition into the passive acceptance of Satan’s descent to claim his territory.

The Kingdom: Exodus may have a demoralizing ending, but the real European society Trier inhabits need not inevitably follow suit. After all, amid the many Towers of Babel, of which the Rigshospitaliet is but one, there remain alongside them thousands of buildings dedicated to the glory of God in Europe that have not yet gone the way of Copenhagen’s bleaching ponds. The magnificent Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris still stands, after all, and is even being restored to greatness, despite the Devil’s best efforts to bring it down. There is hope that as the world gets uglier and less oriented towards human dignity, its most divine and humane things will stand out in starker relief.

But for now, as Trier’s superb show reminds us, we should be prepared to find the good only alongside a hefty presence of the evil.