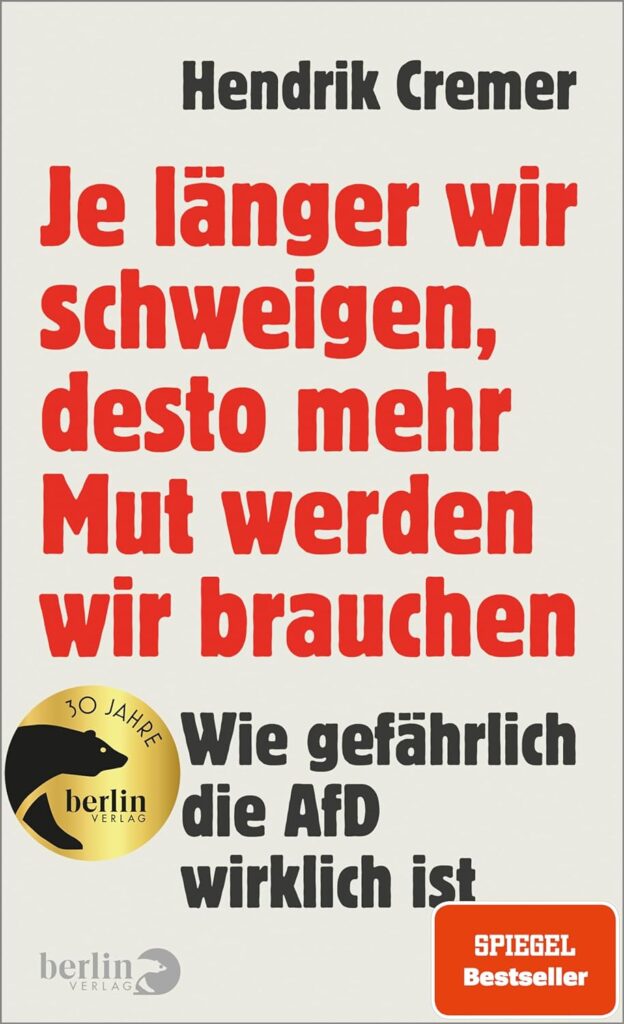

In the back-cover blurb, author Hendrik Cremer characterizes his book as “A well-grounded educational piece that helps readers recognize the extent of the [AfD’s] attack on the liberal democratic rule of law and enables them to combat it effectively.” It is clear that Cremer, a research scholar at the German Institute for Human Rights, makes an honest attempt to achieve that level of solidity. He is sincere, and he deeply believes what he writes. Nevertheless, the book fails to live up to the author’s ambitions. Cremer stays firmly within secularist progressive dogma, and thus fails to engage seriously with those who challenge his presuppositions. The Longer We Remain Silent is little more than a 200-page rant against the Alternative for Germany party (AfD). It follows the standard playbook of establishment progressives (which lamentably includes much of the establishment ‘center-right’).

Cremer’s purpose in his book is to show that the AfD is not just a right-wing populist party, but an extremist and very dangerous party that falls far to the right of what is acceptable in a democratic polity. To drive his thesis home, Cremer incessantly hammers several key phrases into readers’ minds, repeating them again and again like hypnotic mantras. First, Cremer defines the AfD as “an extreme right party that seeks to do away with [Germany’s] liberal democratic order under the rule of law” (die freiheitliche rechtsstaatliche Demokratie). In a variation on the above, he adds that “the AfD aims to abolish human rights, the rule of law and democracy.” Not only that, Cremer asserts repeatedly—without buttressing his claims with any real evidence—that the AfD “strives for massive violence.” If the AfD took power, he warns ominously, “No one in this country would ever be safe again.”

In particular, Cremer is at pains to demonstrate that the AfD is an ideological heir of National Socialism. The fact that National Socialism is a central concern in a book on politics in Germany is, of course, not surprising. And the overriding German concern to banish anything reminiscent of Nazism from the body politic is laudable when it is sober, careful, and fair. While Cremer comes closest to success in this aspect of the book, his argument—that the AfD represents a resurgence of Nazi thinking—is unconvincing.

First of all, in order to bring the AfD within the orbit of National Socialism, Cremer must try to show that the AfD is antisemitic. Here he offers implausible allegations that certain things that AfD members have said are motivated by antisemitism, even if nothing that was actually said had anything to do with the topic. Principal among these is the highly questionable claim that the AfD’s criticism of George Soros, an aggressively progressive man who has donated billions to progressive and anti-Western causes and who happens to be Jewish, really means that the AfD wants to signal to its followers that it is anti-Jewish. The use of this ludicrous claim to try to discredit conservatives is common to progressives. They thereby discredit themselves rather than their conservative targets. Cremer also resorts to the canard that, when sovereigntist AfD politicians criticize globalists, they really mean Jews. He offers not a shred of credible evidence to corroborate this.

Moving on, Cremer claims that “the principal goal” of the AfD is the “creation of a ‘homogenous national community,’” (homogene Volksgemeinschaft). This is “analogous to the ideology of National Socialism,” he avers, since the ideal of the Volksgemeinschaft was important to National Socialist ideology. It is noteworthy that Cremer puts the phrase “homogenous national community” in quotes every time he mentions it, as if he were quoting an AfD document or an AfD leader. However, Cremer nowhere attributes such a quote to the AfD. One wonders: is it a quote from the AfD, or isn’t it? If it’s not a quote, why then does Cremer use quotation marks? Can a party have as its principal goal something that it has never even mentioned?

At any rate, Cremer claims, repeating his mantra, that the AfD’s purported desire to create a “homogenous national community” means that it “is striving for nothing less than the abolition of the liberal democratic order under the rule of law, as enshrined in the [German] Basic Law.” He supports that argument largely by referencing the various party programs of the AfD, especially the Grundsatzprogramm, the Program of Basic Principles, from 2016. Cremer quotes various passages from these documents that argue in favor of “German identity as [the country’s] leading culture” or “the continuing existence of the nation as a cultural unity.” He further discusses passages that maintain that “Cultural relativism and multiculturalism lead to the formation of parallel societies that exist … in opposition to each other” or, in reference to the massive and undeniably disruptive immigration that Germany has experienced from the Muslim world, that “The AfD will not allow Germany to lose its traditional culture because of a falsely understood tolerance toward Islam.”

Extrapolating from these and similar passages, Cremer concludes that the AfD is a racist, anti-Muslim party with a nationalist-folkish (national-völkisch) ideology reminiscent of the Nazis. Without exception, Cremer evaluates these AfD statements not according to their actual content or meaning, nor according to their credibility or accuracy, but exclusively through the prism of what thought and speech is acceptable according to secularist progressivism’s code of political correctness.

I took the opportunity to read two of the AfD’s programs myself: the Grundsatzprogramm, and the most recent such document, the AfD program for the European elections of this coming June. I found nothing indicating that the AfD is anything other than a conservative party—a “civilizationist” party, to borrow from Daniel Pipes—conceived in opposition to what it sees as the German political establishment’s pervasive post-national progressivism. The Preamble of the Grundsatzprogramm summarizes the party’s aspirations for itself, Germany, and Europe as follows:

We are open to the world, but we want to be and remain Germans. We want to preserve and sustain human dignity, the family with children, our Western Christian culture, our language and tradition in a peaceful, democratic and sovereign nation-state of the German people. … As free citizens we espouse direct democracy, the separation of powers, subsidiarity, federalism and the lived tradition of German culture. … in the tradition of the revolutions of 1848 and 1989. … We want to complete national unity in freedom and a Europe of sovereign democratic states that are bonded with one another in peace, self-determination and good neighborliness.

Does Cremer really consider this extreme right, anti-democratic, and reminiscent of Nazism? Either that is exactly what he thinks, or he believes the AfD is lying about itself because it doesn’t share and parrot his secularist progressive assumptions.

As I alluded to above, however, Cremer comes closest to success in his discussion of the outrageous things that various AfD politicians have said over the years, such as characterizing the pro-immigration Merkel government as “puppets of the allies who won World War II,” and expressing pride in the accomplishments of “German soldiers in both world wars.” Given the fact of Germany’s history, such things are troubling, and highly damaging to the AfD. They call into question the party’s willingness to affirm unequivocally that Nazi Germany’s defeat in World War II was a victory for the world against an evil and murderous regime.

Cremer is also right to call out the “brutalization of language” characteristic of some of the polemics which a number of AfD leaders have used in criticizing uncontrolled immigration and the multiculturalist ideology. Similarly, Cremer is correct that the use of phrases by some AfD figures that are reminiscent of the Nazi period—for example, shouting “Everything for Germany,” which was the motto of the vicious Nazi brownshirts of the SA—is unacceptable and deeply troubling. The AfD must take the greatest care to reject and distance itself from all such behavior without qualification.

All in all, I found this book to be much more revealing of the authoritarian bent of today’s progressivist dogma than it is of the AfD. While Cremer rightly calls out the disturbing rhetorical excesses of some AfD politicians, his argument against the AfD is primarily a plea to limit speech and opinion to that which is acceptable to secularist progressive dogma. An author and scholar argued recently in the German magazine CATO that Germany is in the process of transforming itself from a Rechtsstaat, a state characterized by the rule of law and freedom of speech, into a Gesinnungsstaat, a state ruled by politically correct opinion, which tolerates only that which meets with official approval. The Gesinnungstaat is gaining ground throughout the West. Progressives in the EU and North America—activists, academics, and officials—have taken to labeling as a right-wing extremist anyone who departs from officially approved views on any one of a whole gamut of issues: sexuality, gender, right to life, climate change, multiculturalism, open immigration, and all the rest. The implication is that their views should be suppressed, rather than engaged in open and civil democratic debate. Surely, this cannot be what is meant by the freiheitliche rechtsstaatliche Demokratie.