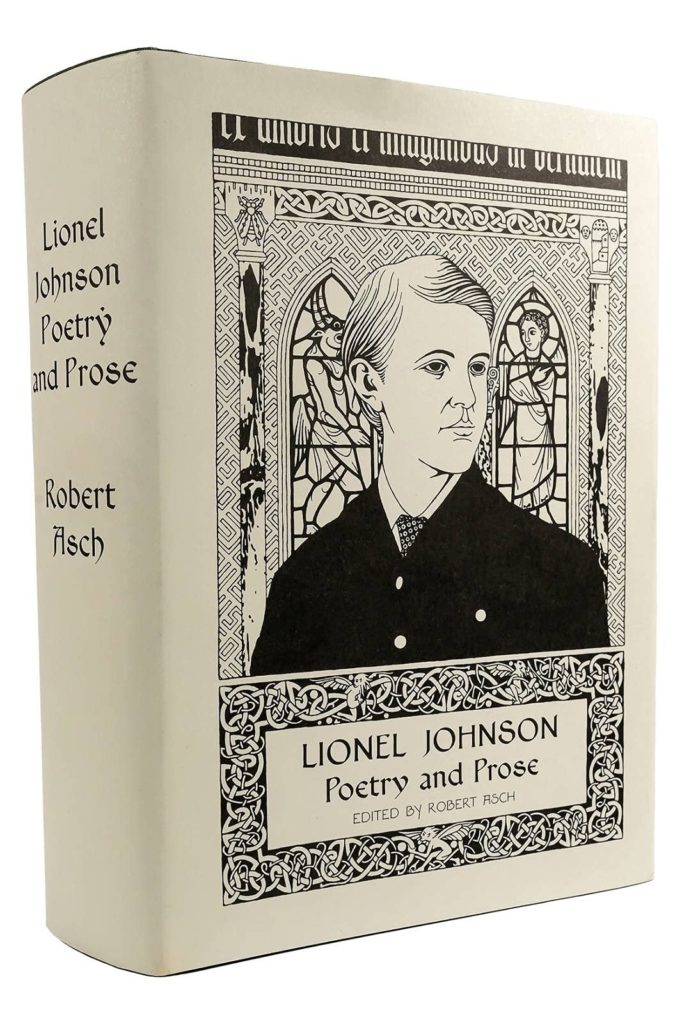

Every now and then, a book comes along that reminds you of just why you love literature and the literary life in general—an emotion, alas, unknown to too many young people to-day. The passion for truth, for beauty, and for goodness dispensed through the medium of words is ever rarer in our day of internet and disinformation, to say nothing of pandemic- and war-inspired doom-and-gloom. But this large and lavish book does all of that, while singlehandedly reviving the life and work of one of the key players in the Catholic Literary Revival of the later 19th and early 20th centuries.

Lionel Johnson (1867-1902), although most often remembered to-day as the man who introduced his friend Oscar Wilde to Lord Alfred Douglas (an introduction he bitterly regretted in his 1892 poem “The Destroyer of a Soul”), appears on the margins of any number of literary biographies in his era. Educated at Winchester and New College, Oxford, he converted to Catholicism the year after graduating from the latter institution in 1890. Deeply learned in Greek and Latin, at once a fine poet and critic, and of a social and kindly disposition, he cut a swath through the “Yellow ’90s,” managing to befriend an endless number of key literary figures of the era, from Yeats, Eliot, and Pound to Guiney, Belloc, and Chesterton. But alcoholism cut short first his career and then his life—although it never dampened his Faith. Having produced only three books during his lifetime (The Art of Thomas Hardy, 1894; Poems, 1895; and Ireland and Other Poems, 1897) and any number of poems and essays for periodicals, he vanished from public consciousness as the generation of writers who knew and for the most part loved him departed this life.

Until recent decades Johnson was primarily remembered for a very few frequently anthologised and extremely beautiful poems. In our own time, due to his friendship with various decadents and his early struggles with his own sexual ambiguities, Johnson has been rediscovered by those elements of the modern literary industry interested primarily in such things. What he awaited was a biographer who shared both his deep Faith and his soaring erudition in order to convey his work both in its true significance to its author, and on its own terms. With Robert Asch, Johnson has at last found him.

So far from lionizing Johnson as the gay icon of current imagination, Asch in this lavishly printed and exhaustive study demonstrates that Johnson found in the chastity his new Church inculcated a peace he had not known before; hence his horror at the results of his ill-starred introduction of his friend Wilde to Lord Alfred. With his close friends and fellow-converts Ernest Dowson and Francis Thompson, he shared a fatal love of the bottle; nevertheless, like them, he was a sincere practitioner of Catholicism. He not only took the teachings of the Church to heart, but was close to such of its stalwarts as Cardinals Newman and Manning. Asch’s thorough-going biography reveals not only just how much Johnson’s religion affected his work, but also how he participated in the various battles of letters the Faith encountered in his time.

Moreover, Asch makes plain just how much a part of the Neo-Jacobite and Cavalier revival of his time shaped Johnson’s politics. Of English birth but of partly Welsh, Scots, and Anglo-Irish descent, Johnson embraced the Irish Nationalism of his time, as well as the greater Celtic Revivalism. But his religion and his Jacobitism allowed him—as it did with such figures and fellow members of the Order of the White Rose as Henry Jenner, Ruaidh Erskine of Mar, and John Hobson Matthews—to reconcile his love of the Celtic Nations with a deep feeling for what was left of “Merrie England.” This was epitomised by his most reprinted poem, “By the Statue of King Charles at Charing Cross.” In the interests of full disclosure, this was the first of his poems encountered by this writer, who to this day brings it up on his cell phone whenever passing the statue at night. I cannot forbear to reproduce the last few final stanzas here:

Armoured he rides, his head

Bare to the stars of doom:

He triumphs now, the dead,

Beholding London’s gloom.

Our wearier spirit faints,

Vexed in the world’s employ:

His soul was of the saints;

And art to him was joy.

King, tried in fires of woe!

Men hunger for thy grace:

And through the night I go,

Loving thy mournful face.

Yet when the city sleeps;

When all the cries are still:

The stars and heavenly deeps

Work out a perfect will.

Asch’s footnote describing the poem is typical of countless such with which he illumines his text:

It … segues seamlessly into Johnsonian concerns: suppressed legitimacy; Jacobitism and the Celtic-British House of Stuart; fate, providence, cosmic and human order; the quasi-Catholic White King—who opposed the anti-Catholic Long Parliament, negotiated with Pope Gregory XV on behalf of ecclesiastical reunion, whose two sons died Catholics, whose Catholic queen venerated Tyburn as a martyrs’ shrine, whose cause was supported by his Catholic subjects, and whose court was dominated by Catholic artists…; and ultimately, the moral and spiritual superiority of authority and beauty (especially in religion and the arts) to power and philistinism.

Indeed, these footnotes—never too long or short, always concise and apropos—are one of the great joys of this book. They turn the biographical essay into a real tour-de-force, as figure after figure of that great era in Catholic literary history appears in context, and each one’s influence by and upon Johnson emerges with great care and clarity. By itself, the book would be a fitting companion to such great recent works as Joseph Pearce’s Literary Converts and Philip and Carol Zaleski’s The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings.

Instead, however, more joys await the reader. First comes “Selected Poems,” many of which have not appeared in print since Johnson’s death—or at all. It too is preceded by a very revealing essay on Johnson as poet, in which Asch first points out the difficulties for the average modern reader. this essay is extremely erudite and filled with references that most of us would not appreciate; this problem he redresses with his usual helpful annotations as the poems proceed. Another issue is that—no doubt because of Johnson’s spurious modern reputation—readers approach his work expecting decadence, and instead are confronted with various themes, among which Asch characterises Cavalier, Catholic, Celtic, Doom, Hymns and Carols, Humorous, and so on. Moreover, he very often crosses these themes—exhibiting four or more in one poem! But by turns sad and ecstatic, funny and triumphant, they will repay the serious reader, thanks to Asch’s expert guidance.

The section “Collected Prose” takes us into primarily unexplored territory. Primarily essays devoted to literary criticism, history, and the occasional whimsical topic, Asch warns us that despite the posthumous publication of three volumes of such work, most remains uncollected in the periodicals for which it was written. He once again offers expert guidance in his introductory essay and footnotes, situating Johnson’s prose work precisely where it belongs in what

might more properly be called the Anglo-American Christian Humanist tradition tracings its patrimony back through Samuel Johnson and Edmund Burke to Swift, Dryden, Ben Jonson, St. Thomas More, and John of Salisbury; but for the fact that—from Coleridge on—confronting the breakdown of the Old Order was central to their oeuvre. As such it includes by extension such men as Newman, Ruskin, Mallock, Irving Babbitt, Hilaire Belloc, Christopher Dawson, and Sir Kenneth Clark—in that their work is concerned with the relationship of spiritual values to life and culture, but is not primarily concerned with literature.

In a word, Johnson is a singularly kindly and good-humoured specimen of the literary Conservative. Foremost in Johnson’s varied output is a love of life and the written word, and of the Tradition that makes both worthwhile. In between penetrating analyses are such lovely pieces as “Christmas Colour,” which surely should take its place among the seasonal favourites. The last sections of the book include selected aphorisms on various topic, letters to different people of note, and several appendices dealing with particular topics, such as an in-depth analysis of Johnson’s “Dark Angel” and Johnson’s relationship with G.K. Chesterton.

To say that this book is a monumental work of affection and erudition is an understatement. On the one hand, Lionel Johnson emerges as a hugely sympathetic figure who bears further exploration as a helpful antidote to the madness prevalent to-day. But by the same token, Robert Asch has created a work whose quality is only slightly (if at all) less than the oeuvre of its august subject. Of course, it is not simply a question of reviving interest in Johnson, but in so many of his contemporaries and what they stood for collectively and individually: Catholicism, beauty, truth, and indeed, goodness. So far from being a candidate for veneration in the ongoing building of a pantheon of LGBT heroes, Johnson emerges as a shining example of one who struggled with personal flaws while fighting the good fight. It is a conflict all who hold high beliefs are burdened with; this book renews one’s confidence that it can be fought with success.