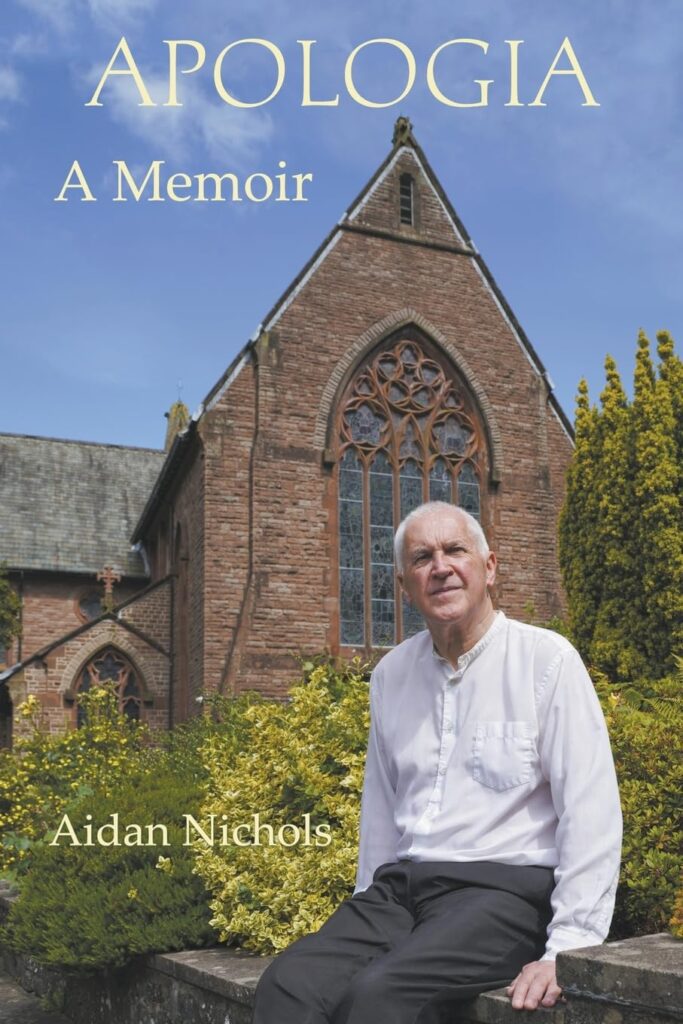

At the beginning of September, 75-year-old Catholic priest Fr. Aidan Nichols released a volume of memoirs, having experienced, with John Henry Newman, the “need to be similarly apologetic” about his life and theological work. Mostly “a human story,” he takes this opportunity to justify some of his actions, as well as to make “an appeal to the Church universal.”

A widely respected academic, with dozens of theology books to his name, Nichols’ choice to criticize Pope Francis turned out to be “life-changing.” A signatory of the 2019 open letter to the Bishops of the world, calling them to correct Pope Francis’s objectively heretical teaching, in Apologia: A Memoir Nichols seeks to offer an overview of his life and how it led to this gesture.

Nichols is plainly a fine writer, and having known him hitherto only though reading a few of his dryer works of theology, I can say that his Apologia is a delightfully relaxed and anecdotal read. Nichols’ love of the mountains and fascination with the role of ‘the beautiful’ in theology and spirituality quickly made me sympathetic to his viewpoint.

For readers eager for gossip, this book is not exactly a juicy ‘reveal all’; it appears that that would be unnecessary. Nevertheless, it is thoroughly candid, and worthy of careful reading by anyone unsure of how a devout, thoughtful, and learned theologian’s career could lead to a valid criticism characterized by one of Nichols’ U.S. Dominican confreres as “unconvincing in both its arguments and its rationale.” Nichols’ often understated or measured style—which Americans might characterize as ‘British reserve’—makes his criticisms of Pope Francis all the more piercing.

As with most biographies, one learns much about the past 70 years through Nichols’ anecdotally rich accounts of his youth and formation at Blackfriars in the 1970s. One learns, for example, of the actively pro-communist fathers of the Priory who earned it the nickname ‘Redfriars’ for a time, and whose activities led to a small bomb blowing in the parlor windows.

With cosmopolitan experience as a friar in England, Scotland, Norway, Ethiopia, Rome, and a handful of other places, Nichols’ writing career began in the ’80s and has continued ever since. The book gives him a happy opportunity to trace the arc of his extensive oeuvre and to explain his exploration of and admiration for certain modern theologians such as Balthasar, Congar, and Ratzinger. Essentially, he saw himself as continuing in the line of John Paul II and Benedict XVI, which Nichols characterizes as “inhibit[ing] the further development of ecclesially damaging trends” through “stabilizing the doctrinal consciousness of the Church.”

“When the reputation of the Vatican has become, it seems, ever more tarnished,” Nichols would “not find joy in traveling again ad limina apostolorum.” As a young convert from Anglicanism in the ’60s, Nichols finds the “doctrinal confusion” of both “Catholic theological culture” and “official statements” considerably depressing, eliciting a sense of “out of the frying pan into the fire” for those “who made considerable sacrifices to ‘come over.’” In this context, members of the Anglican Ordinariates immediately come to mind, especially since Nichols was extensively involved in helping to formulate some of their office books and wrote a number of authoritative commentaries on the Anglican Patrimony in the Catholic Church.

As to continuity of doctrine and present Papal authority, Nichols emphasizes that any “charisms” of the Roman Pontiff “must be tested by their fidelity to what is already given in the apostolic tradition—not least as received in the historical succession of the bishops of Rome.” As Nichols succinctly states, “A ‘God of surprises’ is one thing. A God of reversals is something else altogether.”

Quite simply, the message of the Church which “theologians convey must be both rich and clear.” Richness, for Nichols, includes “learning diachronically from other generations of the Catholic Church and learning synchronically from non-Catholic Christians, notably the Eastern Orthodox and Anglicans.” For the Faith that glories in calling itself ‘apostolic,’ Rome is the source whence clarity comes. “So how could obfuscation of the clarity richness requires begin from—of all places—Rome itself?”

When Nichols signed the 2019 letter it was because of this fact: that Rome could not be a source of confusion except as an anomaly. “If, as a schoolboy of seventeen, I had been required to abjure heresy, why should not a pope, confronted with his own at best ambiguous statements, be equally required to affirm orthodoxy?” For Nichols, the “gains in charity made by the previous two pontiffs were at stake. Prominent in the press, the language of the ‘heresy letter’ was “certainly strong.” “But the seriousness of the situation,” Nichols tells us, “called for a kind of description that eschews diplomatic formulae of an ambiguous kind.”

At stake were the implications of papal support for the heretical interpretation of Amoris Laetitia and the Abu Dhabi Declaration. Nichols expected (naively, he wonders) that a substantial portion of the hierarchy would “take a stand on the chief issues involved.” “The deafening silence that ensued” upon the letter’s publication “was disorienting, not to say subversive.”

A “significant preliminary” to signing the letter was the encouragement Nichols received from Archbishop Augustine DiNoia, Adjunct Secretary of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, regarding Nichols’ analysis of Amoris Laetitia in a controversial lecture given in 2017. The lecture noted how Amoris Laetitia implied positions condemned as heretical by the perennial teaching of the Church, including the Council of Trent, as well as Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI. Essentially, Amoris Laetitia opened the door to “a previously unheard-of state of life. Put bluntly, this state of life is one of tolerated concubinage.” Not only that, this papal document seemed to say “that actions condemned by the law of Christ can sometimes be morally right or even, indeed, requested by God” and that it might be impossible for a Christian in a state of grace to observe the commandments—a view directly anathematized by the Church.

In this important lecture—the text of which is not available in full—Nichols asserted (as reported by the Catholic Herald):

It is not the position of the Roman Catholic Church that a pope is incapable of leading people astray by false teaching as a public doctor. He may be the supreme appeal judge of Christendom … but that does not make him immune to perpetrating doctrinal howlers. Surprisingly, or perhaps not so surprisingly given the piety that has surrounded the figures of the popes since the pontificate of Pius IX, this fact appears to be unknown to many who ought to know better … It may be that the present crisis of the Roman magisterium is providentially intended to call attention to the limits of primacy in this regard.

Nichols in turn proposed that canon law required “a procedure for calling to order a pope who teaches error.” Archbishop DiNoia, having seen the presentation reported, requested the script and, after reading it, told Nichols that “it was the most satisfactory account of the document he had seen” and that he thought that theologically “the pope’s position was hardly defensible.”

“Such words”—which Nichols “gently paraphrases”—“coming from so informed a source, made a profound impression” on him and followed as they were by the Abu Dhabi Declaration which seemed to contradict the ‘Great Commission’ of spreading the Gospel to every creature, bred in Nichols “a resolve to do, in this ‘New Church Crisis,’ whatever might be in my power.” As it happened, this included a journey to Moscow to ask Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev whether or not the Church of Russia could ask the Church of Rome to renew its commitment to “proclaiming the shared evangelical faith.” Although the proposition was positively received in a private meeting with the Metropolitan, Nichols does not know whether or not anything came of it.

Nichols’ signing of the letter elicited displeasure from his superiors: an ‘exile’ to a seminary post in Jamaica followed, as well as the realization that he was no longer welcome in England, leading to a search for a new home in which to spend the twilight years of his life. It is worth noting how the signatories of the 2019 letter have been somewhat vindicated by the steadily increasing number of prominent figures who openly criticize the words and actions of Pope Francis. For example, Cardinal Sarah recently asserted in Rome that there is a “crisis of the Magisterium” and Cardinal Müller, a theologian so esteemed by Benedict XVI that he was placed in charge of the then Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, said in a November 2023 interview that “some of Pope Francis’ statements are formulated in such a way that they could be reasonably understood as material heresy.”

For Nichols—and I think he speaks for innumerable faithful Catholics—“the most immediately pressing concern” is the fact that the Holy See “cannot sacrifice its reputation for doctrinal clarity and expect to hold its place in the confessional scheme of Christians.” Although the 2019 letter was reported as a “traditionalist” initiative on account of signatories like my father Peter Kwasniewski, Nichols’ confrere Fr. Thomas Crean, and the Ordinariate priest Fr. John Hunwicke, it should be clear from this book that Nichols himself does not consider himself a traditionalist, strictly speaking. Nichols deserves a hearing from everyone precisely because, whilst he comes to some of the same conclusions as many traditionalists, he comes to them by a different path which includes extensive use of modern theology, arguably at its best. As Bishop Paul Swarbrick comments in his short Foreword: “I am happy to offer it [this book] my personal commendation largely because of the challenge it presents to me.”

Thanks to Nichols’ Apologia, we have not only an entertaining account of the author’s life and journey to offer a context for his many books, but also a reminder of the ‘practical corollaries’ to which love of the Church leads when it comes under attack. “All who truly love the bridal Church have the capacity, in their time, place, situation, to awaken the sleeping beauty with a kiss,” Nichols writes on the last page.

Beyond the visible aspect of the Church and her teaching office lies the “mystery of the Church as Bride of Christ.” Fostering a deeper love for her will lead us both to work for the healing of her earthly condition, bound up as it is with the supernatural destiny of souls, and to remember that this earthly wounded reality is not the only facet of the Church. In her perfection in heaven, in the saints, the Church forever remains the immaculate spouse of Christ. Nichols’ ‘amen’ to Chesterton’s desire for a “Church that will move the world” rather than be moved with it ought to be ours also, if by ‘Catholic Church’ we mean anything coherent with the institution founded by Christ and existing for the past 2,000 years. Anyone desirous of uttering a similar amen in the course of life, and yet confused as to what that might entail, could benefit from reading this autobiography.