What, precisely, constitutes a ‘classic’? This is a question that should interest any conservative. This is because the word classic does not merely communicate ideas of age and venerableness, but it also tells us that a work is to be taken as artistically (or even morally) normative. To say that Aeschelus’ Prometheus Bound, Dante’s Divine Comedy, or Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony are classics, while E. L. James’ Fifty Shades of Grey and Michael Bay’s Transformers are not, is to make a judgement that is not purely historical or even just aesthetic: it is somehow civilizational. What our culture sees as a classic both expresses what we as a civilization value and naturally molds our methods of education. Thus, our canon of classics forms us—especially when young and impressionable—to admire and love, not just certain works of art, but also certain ways of living.

This is why I was so struck to come upon a volume of Penguin Classics’ new series of mid-century Marvel comic reprints. This isn’t the first time Penguin Classics has made a controversial decision. Think, perhaps most famously, of their decision to publish the autobiography of British musician Morrissey, of Smiths fame. Still, though, seeing Spider-Man, Captain America, and Black Panther comics collected within the covers of the iconic Penguin Classics editions is startling. The collection currently consists of the three volumes named above, though it is Penguin’s intention to publish at least three more.

I have previously argued in this column that comics are a distinct art deserving of our attention. However, even I hesitate to see these Marvel comics, originally written at breakneck speed for a juvenile audience and printed on low-quality paper, placed beside Dickens and the Iliad. That being said, I have decided to give these volumes a fair shake and consider each on its own merits. Whether or not these ought to qualify as classics, they each boast virtues (and entertainment value) that merit our attention.

First appearing in 1962’s Amazing Fantasy issue 15, Spider-Man is one of the world’s three most famous superheroes, along with DC’s Superman and Batman, and arguably one of the most famous fictitious characters of the last century in any medium. His basic story is well-known, but it is worth recalling. Peter Parker, a bookish and socially-awkward teenaged orphan, lives with his doting Uncle Ben and Aunt May in New York City. One day, he is bitten by a radioactive spider, gaining the ability to stick to walls and the proportionate strength of an arachnid. He then designs a flashy spider-suit and develops a “web fluid” that allows him to swing from building to building. However, his response is surprisingly unheroic: instead of fighting crime, he seeks fame and fortune as a masked TV performer. His new powers go to his head, and he even refuses to stop a criminal who runs right by him.

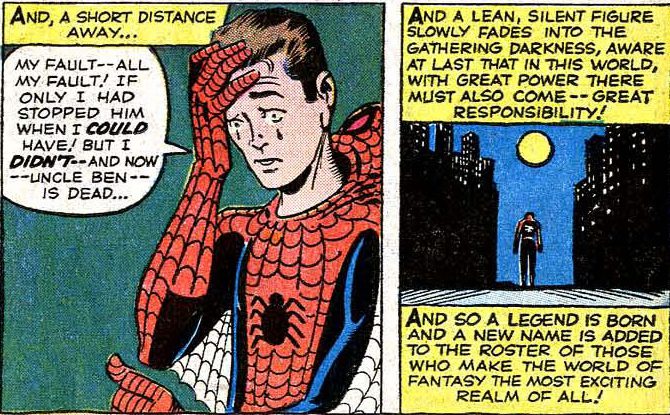

One night, Peter’s Uncle Ben is murdered. Furious, he tracks the killer down in hopes of exacting revenge. When he discovers the man, though, Peter sees that this is the very criminal that he had refused to lift a finger to stop. Peter himself is responsible for the death of his uncle. After capturing the murderer and leaving him for the police, Spider-Man finally confronts the obligation that has been thrust upon him. In an iconic image, he walks alone into the night as the narrator tells us that “with great power there must also come—great responsibility!”

This line—which, as I have previously observed, echoes the Biblical injunction in Luke that from “him to whom much is given, much is expected”—is perhaps the most famous line in Spider-Man’s history, and with good reason. It serves, both explicitly and implicitly, as a kind of coda for every version of Spider-Man that has ever graced the printed page, the radio, or the silver screen. Peter Parker is written as a deeply sympathetic character who has been given the opportunity to help prevent others from suffering the kinds of injustice he has experienced, and yet the guilt of his initial failure is always present.

The original comics, reprinted in the Penguin edition, are written by Stan Lee and illustrated by Steve Ditko. Ditko’s art is consistently visually arresting. In a time when Batman and Superman were generally written as paper-thin characters without a whiff of complexity, Ditko’s skinny, awkward Peter Parker evokes powerful emotions in readers. And more than that, Ditko’s illustrations pull us into an entire world, a world of dirty kitchen sinks, dark alleys, and profound human drama. While I am a great fan of Stan Lee’s scripting regardless of the artist, the Lee-Ditko collaboration on Spider-Man stands for me as the perfect combination. Somehow, Lee’s Shakespearian-inflected prose and Ditko’s Raymond-Carver-esque art balance each other perfectly. (Sadly, Ditko and Lee’s relationship eventually deteriorated to the point that Lee ceased writing the scripts until Ditko ultimately left Marvel.)

The hardcover Penguin Classics edition of these early Lee/Ditko stories—like the Captain America and Black Panther volumes—is excellent. The paper is high-quality and slightly yellowed, standing up to use while simultaneously reminding readers of the original newsprint comics. (Unfortunately, when perusing a copy of a paperback edition, I got the impression that the bindings of the paperbacks just weren’t up to snuff to the kind of use comics and graphic novels get. Hopefully Penguin fixes this issue, but until then, I recommend springing for the hardback.) The book boasts a short forward by novelist Jason Reynolds and a more scholarly introduction by series editor Ben Saunders. Whatever my disagreements with Reynolds’ politics, his forward is stellar, excellently expressing Spider-Man’s universal appeal in accessible language.

Despite the many virtues this edition possesses, there is one major drawback: it includes only 12 of the first 20 Spider-Man stories. Thus, I am quite glad that I possess the first two volumes of Marvel’s slightly smaller paperback Mighty Marvel Masterworks editions of Spider-Man, collecting the same period of comics without any gaps. Overall, though, I can highly recommend the Penguin classics Spider-Man volume. The stories are moving, dealing with perennial themes of interest to conservative readers, and the art is one-of-a-kind.

Captain America, first created during World War II to help with the US’ war effort, is an odd figure to confront today. At the beginning of the first comic, published slightly before the United States entered the war, a scrawny young man named Steve Rogers volunteers to receive the “super soldier serum,” an experimental new solution that, if successful, will grant him phenomenal strength. The experiment is a success, but a spy working for Germany assassinates the scientist who developed the serum, meaning that the Allies will never have another super soldier. Rogers steps up as “Captain America,” fighting for justice against the enemies of freedom.

In a time when both liberals and conservatives are uncomfortable in various ways with the nation’s role on the world stage, many write Captain America off as little more than a jingoistic figure punching out the dirty Nazi menace. Thankfully, Gene Luen Yang’s forward confronts the character’s seeming incongruity with the contemporary world. Yang (an excellent graphic novelist who integrates questions of national identity with his own Catholic faith) writes of how as a teenager he and his best friend mocked his younger brother for reading Captain America comics. Later in life, though, he returned to Captain America’s comics and realized he had been missing a lot. Though Yang inclines towards using the terminology of “progress” in his defense of the hero, he ultimately justifies Captain America as a beacon of hope. Reading these comics, which possess a sense of moral rightness difficult to find in media or politics today, leaves one with a sense of promise. They tell us that growth and virtue are possible.

Despite the fact that Captain America has never been one of my favorite comic characters—or even superheroes—coming to these stories as an adult has proved valuable. The Penguin Classics volume includes comics from the 1940s and ’60s (as well as an appendix about the short-lived 1954 Captain America… Commie Smasher!). Those from the ’40s, in addition to being more violent than the later works, represent a simple optimism about American life and ideals that, though still present, are noticeably diminished in the ’60s version penned by Stan Lee. It’s not that these later works are in any way unpatriotic, but they are more honest about the tolls of war and the challenges that face Westerners. In them, Steve Rogers, perfectly preserved in ice since the war, is discovered and thawed out. His best friend, Bucky, is dead, and his beloved is lost. Rogers, prone to bouts of melancholy (and perhaps even suffering from PTSD), struggles far more as a hero. Yes, artist Jack Kirby’s drawings leap off each action-packed page, but there is a sense that these punches hurt not just the enemies of freedom, but also its defenders.

Despite my general appreciation for classic comics, I could not help feeling that these old Captain America stories, though fun, lack the depth of either early Spider-Man or Black Panther. While the Captain deals with isolation, his struggles simply don’t feel existential in the ways Spider-Man’s do or civilizational in the way Black Panther’s do. In addition, the visual storytelling by Kirby, despite its iconic status, isn’t as compelling to me as Ditko’s on Amazing Spider-Man or Graham’s on Black Panther. Captain America will likely never be my personal favorite superhero, but this volume is still worth the interested readers’ time. Its tales of a patriotic hero who calls his nation to be all that it can are inspiring, and, speaking from experience, they are quite adept at providing several afternoon’s entertainment for young and old alike.

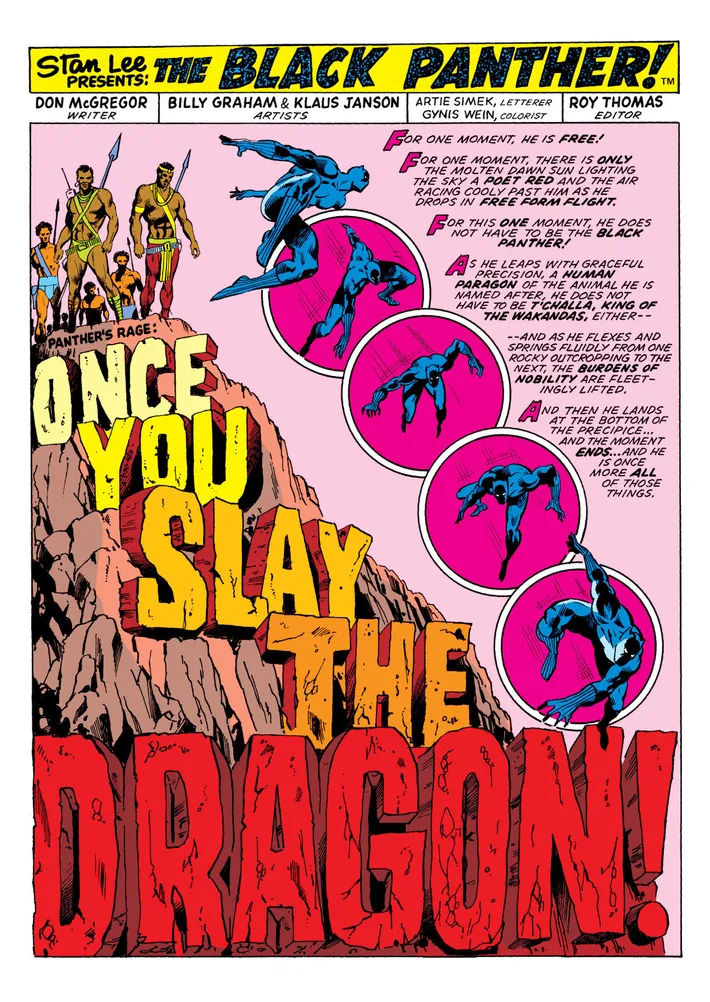

Above, I praised The Amazing Spider-Man comics at some length. In so doing, I might fairly be accused of nostalgia (Spider-Man has been my favorite superhero since childhood) or even political bias (Steve Ditko, while no traditionalist conservative, was a card-carrying libertarian, and this influenced his comics). However, neither accusation can be leveled against me for the last comic being discussed today, as it has long had liberal associations, and I hadn’t even heard of it until I was in my mid-20s. All the same, the Black Panther comics published in the Penguin Classics edition are exquisite from beginning to end, and I barely have the words to praise them. Constantly dealing with questions of justice, obligation, kingship, nationhood, and technology, this book alone makes a very good case for the inclusion of Marvel comics alongside, if not Homer and Plato, at least Fitzgerald, Waugh, Gilson, and Camus.

The Black Panther, first introduced in a two-part story (included in the Penguin Classics edition) in the Marvel comic Fantastic Four and years later given his own comic, is a strange Marvel superhero. Yes, he has powers and tries to do right, but instead of being a lonely, bullied teenager from Queens (like Spider-Man) or a scrawny do-gooder from Brooklyn (Captain America), the Black Panther is the fabulously wealthy T’Challa, king of the technologically advanced (and virtually unknown) African nation of Wakanda.

This fictitious country, Wakanda, is a fascinating world for the comic to inhabit, and—despite discussions of the culture and the inclusion of Tolkien-esque maps—readers are always left wanting more time with the unique nation. Geographically secluded, Wakanda is the beneficiary of a mountain of vibranium, an extremely valuable, very powerful, and utterly unique element that can only be found in this isolated place. Because of the presence of vibranium, Wakandans have long been far more technologically developed than not only the rest of Africa, but the Western world as well. And yet, they still live simply in many ways, with tribes and rituals reminiscent of every healthy, pre-modern society. This allows for the integration of highly-advanced technology into a strong, traditional culture that should interest any conservative concerned with how these two things can coexist.

In addition to the concepts animating the story, I would be remiss if I didn’t focus for a moment on the astonishing visual storytelling throughout the volume. After the first 60 pages introducing Black Panther (by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby), the book is written by Don McGregor and illustrated mainly by African American artist Billy Graham (with assistance from Rich Buckler and Gil Kane). This team worked together seamlessly, but I want to focus for a moment on Graham’s impeccable artwork. Throughout the volume, readers are treated to drawings that perfectly communicate the mood in any room, from character’s posture to the presence (and absence) of objects. While I have never been one for extended action scenes, Black Panther’s fights are a sight to behold. Perhaps my favorite example is when the Black Panther is thrown down a waterfall by his nemesis Killmonger. The splash-panel takes up two pages of the book, and it simultaneously shows the water coursing powerfully down to the rocks while also drawing the reader’s eyes across a series of close-ups of the Black Panther’s fall, giving an almost film-like quality to the pages.

It would be hard to overstate how taken aback I have been by the quality of every aspect of these comics from the 1970s. I could go on at far more length about the virtues of this comic, but I will satisfy myself by simply recommending you read the volume yourself. You won’t be disappointed.

But what about the question that opened this article? Are the best Marvel comics deserving of the label classics? The simple answer is that I don’t know. A classic in the fullest sense cannot be determined by a single man’s opinion. Instead, classics are those works that prove themselves over time by providing beauty and meaning to generations. All I can say for sure is that this is what Marvel comics have done for me. Whether or not they do this for our civilization, only time will tell.