Before writing and illustrating the hit Belgian comic Blake and Mortimer, before assisting in the making of Tintin, before becoming a master of the ‘ninth art,’ the young Edgar P. Jacobs published a comic called Le Rayon U (The U Ray). A pulpy adventure story populated by genius scientists, dashing heroes, nefarious spies, hulking dinosaurs, and semi-civilized ape-men, it is an odd and uneven book. Yet it was beloved on its initial release during World War II, and it remains a cult classic to this day.

The U Ray has a sense of adventure and a frenetic energy all its own, especially in the slightly updated version the author published in 1974. Like Jacobs’ best-known work, it has helped to inspire one of the greatest living Belgian comics writers, Jean Van Hamme. Having spent decades writing some of the most popular bande-desinee series ever (e.g., Thorgal, XIII, and Largo Winch), Van Hamme has, in his ‘semi-retirement,’ written a sequel to The U Ray, entitled La Flèche Ardente (The Fiery Arrow), both recently released in English by Cinebook. This continuation of the story simultaneously stays true to the original’s pulpy origins and seat-of-the-pants imaginativeness while deepening the story and developing some of The U Ray’s more half-baked elements into what feels like a complete saga. By making use of old pulpy cliches, both works remind us that even somewhat formulaic comics can entertain and, if well-illustrated, engrave themselves upon our memories.

The first thing to know about The U Ray is that it is inspired by Flash Gordon comics, even to the point of being called a rip off. I don’t mean this as an insult to the work or its author; the original Star Wars trilogy is in large part inspired by Flash Gordon serials, and it’s one of the greatest film series ever made. Additionally, The U Ray is ‘pulpy.’ If you’re unfamiliar with the term, it derives from pulp fiction: novels and short story collections that were so-called because of their low quality (“pulpy”) paper.

While the term has always had negative connotations, there is a freedom that comes with pulp fiction. Since they were relatively cheap to produce, pulpy publishers would often print more experimental works of genre fiction, especially science fiction and fantasy. The works of H.P. Lovecraft, for instance, may never have become beloved—or even been published—if it weren’t for this willingness to experiment.

Many comics over the years have taken inspiration from pulp fiction. Sometimes the inspiration is direct, as when Hal Foster, best known for Prince Valiant, made a name for himself by drawing a comic version of the pulp novel Tarzan of the Apes. At other times, pulp works provide cartoonists with certain tropes and cliches they can work within—and carefully break out of. Flash Gordon, the inspiration for The U Ray, was itself in turn profoundly influenced by this kind of tropey writing.

While as a young man E.P. Jacobs dreamed of becoming an opera singer, he was a talented illustrator, and by the advent of World War II he had taken a job doing illustrations for a Belgian children’s magazine called Bravo. The magazine published a number of different comics, including the extremely popular American comic, Flash Gordon, created by Alex Raymond. However, during the occupation of Belgium, Nazi censors prevented the comic from being published. Bravo in turn asked Jacobs to continue the story and give it an ending so that readers did not feel cheated. This he gladly did, bringing the long-running story to a swift conclusion over the course of a few weeks. Soon after, Bravo had Jacobs begin a new series in the style of Flash Gordon, and this is what would become The U Ray—for more details, see my previous review of the Jacobs exhibit at the Belgian comic museum.

In The U Ray, two nations—the Austradians (the ‘baddies’) and the Norlandians (the ‘goodies’)—are at war. A Norlandian scientist, Professor Marduk, has developed a new technology (the titular U ray) that could mean victory in the war. Despite its title, the “U ray” is never seen, and it is more a framing device to get the adventures started than a significant part of the plot. The U ray needs the (fictitious) element uradium to power it, and uradium is only found on a strange and uncharted island. Thus, the scientist, his beautiful female assistant, and several others are off on the adventure of their lives on the island.

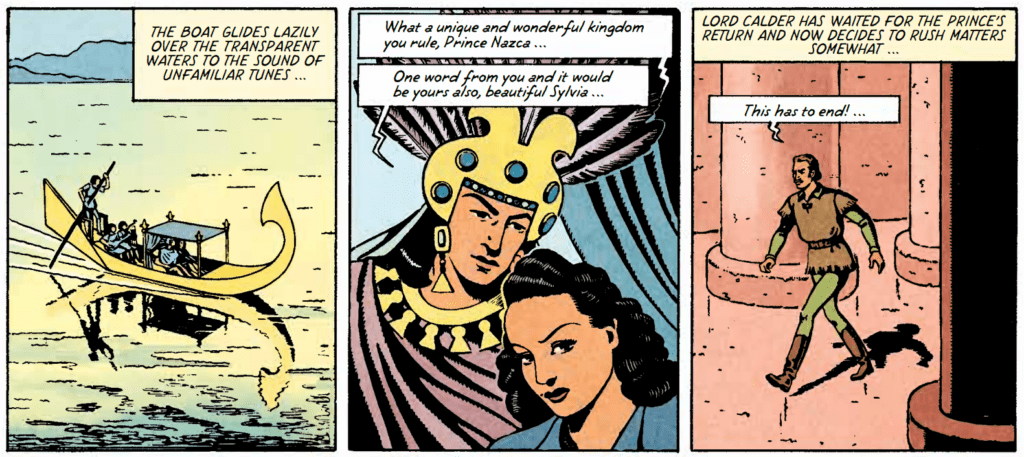

The lack of character description in the last paragraph was intentional; there is very little to say. The book has goodies and baddies and, with the exception of the native king of the island, Nazca, and his betrothed, Ica (whom the adventurers meet on the island), the characters have virtually no motives other than finding the uradium and staying alive. The most amateurish aspect of The U Ray is its characters. Jacobs clearly had never conceived of his own characters before, so while each one is visually compelling and distinct—showing Jacobs’ artistic talent and dedication—their personalities are close to nonexistent. Jean Van Hamme, thankfully, has ample experience inhabiting the minds of fictional characters, so this defect is largely remedied in his sequel.

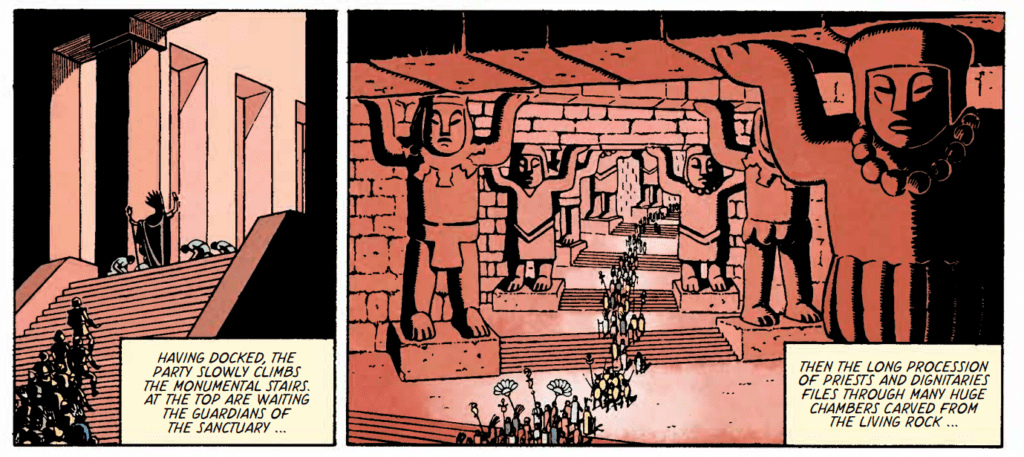

But enough about the comic’s slight weakness—it has far more strengths. To start with, it is imaginative. Once on the island, the explorers meet with dinosaurs, ape men, and a foreign civilization, all of which are beautifully realized. This is an area where Jacobs excelled for his whole career. As I put it when writing about Blake and Mortimer, he was able to “craft fully fleshed-out worlds that draw readers in, making us sad to leave at the end of each work.” In this respect, Jacobs’ seems to have begun his career with as much energy and inventiveness as he would later show in masterpieces like The Time Trap.

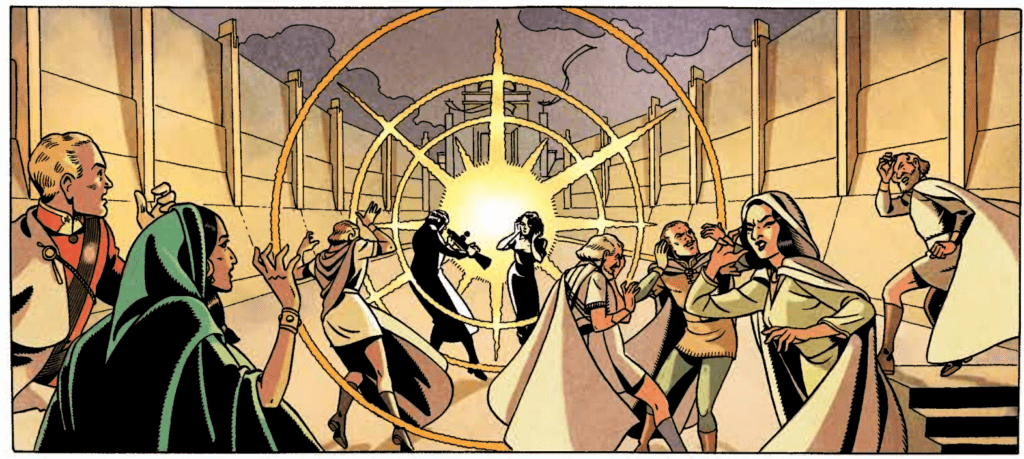

The art is also a joy to behold. The edition available for purchase in French and English benefitted from Jacobs returning to the work and improving it, but the original art (some of which can be seen here) already showed how Jacobs was beginning to develop his own style within the ligne clar tradition. Even when updating the comic, Jacobs generally polished the art without radically changing it. As a result, human figures have a stylized appearance that can feel a bit stiff, but this was, I think an intentional harkening to the formal posturing of sci-fi heroes of the time.

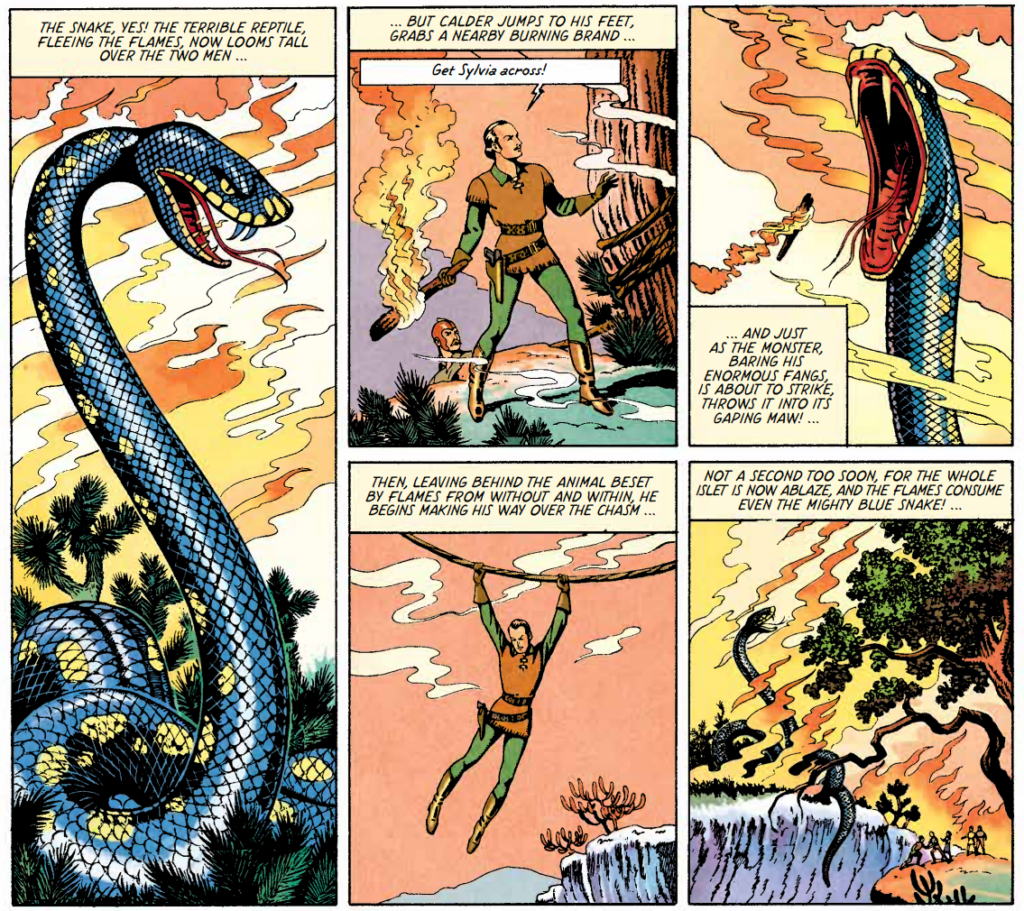

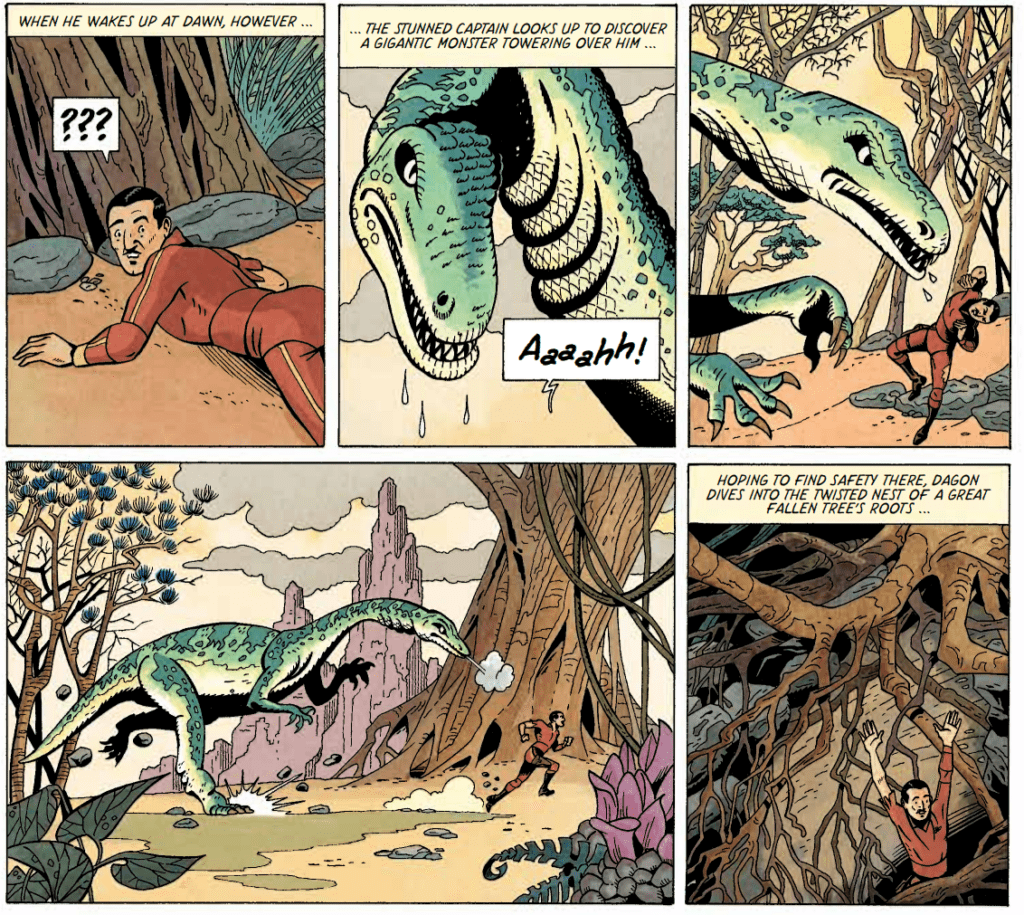

As is always the case with Jacobs’ work, readers are invited to delight in the world of the comic. The various locations on the island feel like somewhere any adventurer would like to see (albeit with some protections against the malevolent forces found there). Somewhat unusually for Jacobs, many fantastical beasts appear in The U Ray, and they are powerfully rendered. Some of the most attention-grabbing images of the comic are of these beasts, and the mastery with which they are depicted makes me wonder why Jacobs so rarely depicted such creatures in Blake and Mortimer.

All-in-all, The U Ray is great, pulpy fun. However, while it does have a kind of thematic unity with one of Jacobs’ characteristic morals about the relationship between science and our life together (something he would improve at integrating in later works), it does feel somewhat wooden and incomplete at points. It is thus no surprise that, in our age of sequels, prequels, and remakes, someone would try his hand at continuing the story.

One of Jean Van Hamme’s first memories is having one of Jacobs’ comics, the first Blake and Mortimer, read to him by his uncle. As an adult, he became the author of some of the most beloved bande dessinée of all time (many of which are available in English translation from Cinebook). After becoming a respected comic writer, his childhood dream was realized: he was given the opportunity to script an official Blake and Mortimer continuation. His first contribution, The Francis Blake Affair, is considered one of the best in the series.

Van Hamme is now in his mid-80s, and over the last decade he has moved on from writing his regular series. But this doesn’t mean he’s done writing comics; today he prefers to take on smaller, shorter projects. Despite this, his editor was confused when Van Hamme said he wanted to write a sequel to The U Ray, and the editor wanted to know why. Van Hamme’s answer was simple: he thought it would be fun. He explained that, despite his characteristic style being quite different from that of Jacobs’, he would stay true to the spirit of the original. As he put it, “I’m going to do a sequel, but I’m going to do it in the same kitsch style.” This style clearly agreed with him; Van Hamme surprised himself by writing the script for The Fiery Arrow in just a month and a half.

While it is true that Van Hamme kept to Jacobs’ style, he has elevated it. Though I am generally somewhat suspicious of sequels written decades later by people other than the original author, in this case I actually enjoyed The Fiery Arrow even more than the original. While the story feels like a natural continuation of its predecessor, Van Hamme clearly gave more thought to the motivations of the characters in the story. Don’t get me wrong—it’s still pulpy. But the pulp is enhanced by melodrama that feels in keeping with The U Ray’s spirit.

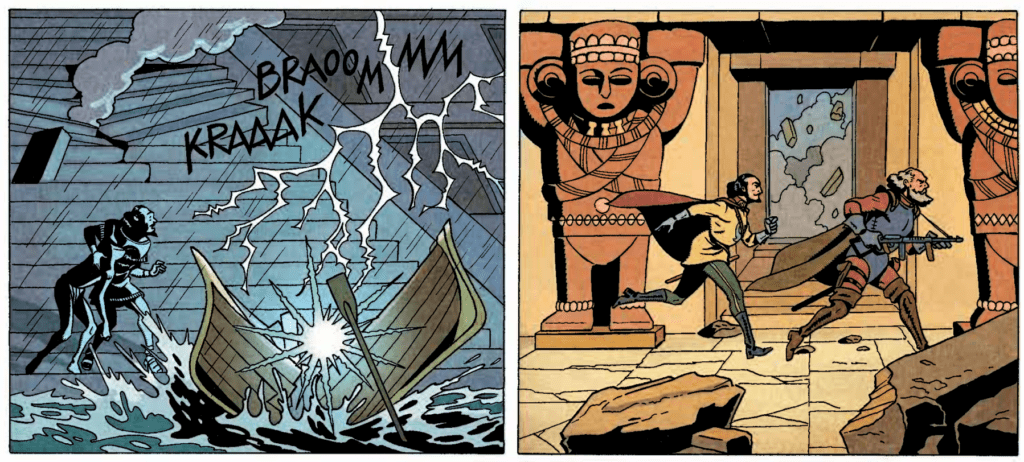

This melodrama is both of the romantic sort (with several couples coming out of the book) and the cultic. In The U Ray, the explorers were warned by natives that the uradium, while granting godlike power, is a dangerous, even vengeful, divinity. Van Hamme picks up this idea and develops it well, showing some of the dangers of modern technology and man’s domination of the earth.

The art for The Fiery Arrow was done by Christian Cailleaux and Etienne Schréder, both of whom have previously worked in Jacobs’ tradition by illustrating volumes of Blake and Mortimer. Given that experience, they were able to do a good job making the book feel like a continuation of the original. The Fiery Arrow’s people, like those of The U Ray, are somewhat stylized. During a few action scenes, conflict is depicted a bit more interestingly than Jacobs did in his original, which is all to the good.

To understand why The U Ray is so beloved nearly a century after its initial publication, and why one of the greatest living comic writers would put his prodigious talents to work penning a sequel, it’s important to realize the fact that simple, good-versus-bad, tropey, pulpy fiction is, when done well, fun and even sometimes rewarding. To illustrate this point, it might be helpful to look at another pulp work, The Maltese Falcon (the inspiration for the Humphrey Bogart film of the same name). The story has every detective-story cliché in the book: the noir aesthetic; the well-dressed, smooth-talking private investigator; the femme fatale; the MacGuffin; and quite a few more. When people read the book (or watch the movie) for the first time, they might well anticipate various story beats; but even in so doing they are unlikely ever to be bored. There is a mastery with which these conventions are used and occasionally reversed. The same is true of The U Ray and The Fiery Arrow.

The U Ray is not a perfect work, but it is bursting with a sense of adventure that is so important in this kind of comic, and its art allows Jacobs’ genius to shine forth. Jacobs wrote his work at the very beginning of his career, while Van Hamme penned The Fiery Arrow in the twilight of his own. Thus, they make for striking bookends that revel in their pulpiness, and they are well worth the time for any fan of either author, or of the genre as a whole.