In a previous column, I briefly discussed the two most famous comics of the Franco-Belgian tradition, Tintin and Asterix, both of which I was lucky enough to be exposed to in childhood. This was somewhat unusual for an American, as until the advent of online shopping they were rather difficult to come by in my country, and even in the post-Amazon landscape one needs to know to look for them! But exposed to them I was. I devoured the eight or so Tintin volumes in my family’s collection, reading them over and over again, and the three Asterix comics—even rarer and more obscure than Tintin—were worth far more than their weight in gold.

These two comics series, despite being hard to come by in America, were at least consistently available in English. But what of the many other French-language comics that have been beloved by generations of Francophone readers? Unfortunately, they generally remained untranslated and undistributed in Anglophone markets. This meant, of course, that my childhood self had no opportunity to enjoy them. Thankfully, for the last 17 years the British publishing company Cinebook has been translating these treasured comics into English and making them available across the world.

One of the Cinebook releases that my childhood self would have been most jealous of my current access to is Spirou and Fantasio. This series, in publication by various authors since 1938, is generally best remembered for the twenty volumes by André Franquin, whose works I will be focusing on here. Franquin’s work on the comic is exuberant and lighthearted while often simultaneously making political and social commentary that, despite being lost on most younger readers, can be enjoyed by adults. Ultimately, though, to read Franquin’s comics is to blur the line between child and adult and to enter a world of wonder of which we could all use a taste.

The character of Spirou was first drawn by artist François Robert Velter (better known by his pen name ‘Rob-Vel’) in 1938. In the imaginative first comic strip, Spirou literally walks off the artist’s page in response to an advertisement for a position as a bellhop. (In time Spirou would change professions, becoming a reporter, but he has never lost his iconic red bellhop uniform.) Velter’s comics, following Spirou and his squirrel companion Spip, were generally centered around silly gags, eschewing serious drama. They proved quite popular, and the publisher expressed interest in purchasing the comic. Unusually for the time, Verlter sold the rights to the strip and characters, meaning that others have since been able to write and draw stories for Spirou—and write and draw they have! To date, more than 20 writers and artists have tried their hand at it. The most famous, though, are André Franquin (who helmed the comic from 1947 to 1969) and the team of Philippe ‘Tome’ Vandevelde and Jean-Richard ‘Janry’ Geurts (1984-1998).

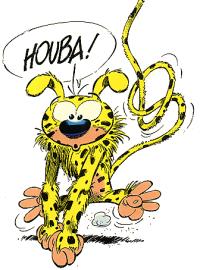

Franquin, on taking over the comic from Joseph (‘Jijé’) Gillain in the late 1940s, began to develop longer stories, and that was when the real fun began. Jijé had introduced the character of Spirou’s best friend, Fantasio, but Franquin greatly expanded the Spirou universe. In addition to fleshing out Fantasio’s hot-tempered character, he introduced the eccentric scientist Count Champignac, the adventurous female reporter Seccotine, and—most famously—the long-tailed and tigger-ish jungle animal, the Marsupilami.

After producing 20 comic albums (or 21, depending on who’s counting), Franquin stepped away from Spirou and Fantasio in 1969. While the next two eras have their fans, they are nowhere near as beloved as Franquin’s. Jean-Claude Fournier, who took over from the master, attempted to modernize the comic, in part by bringing politics from the background onto center stage in some stories. But it really wasn’t until Tome and Janry began writing and illustrating the series in 1984 that the comic experienced a renaissance.

While deeply influenced by Franquin’s art and stories, the Tome/Janry comics have their own distinctive personality. The storytelling is slightly more compact (generally running 45 pages instead of Franquin’s customary 65), and these comics have a certain edge to them that Franquin’s works do not possess. Don’t misunderstand—they’re still great fun, but even their first work, 1984’s Virus, tackles biological warfare, albeit in comical ways. Janry’s art clearly stands in the tradition of Franquin, but it is somehow more ‘scratchy,’ possessing a certain earthiness. In addition, it’s more detailed than the older comics, with lovingly crafted backgrounds.

Oddly, the team also developed a spin-off called Le Petit Spirou (“Young Spirou” or “Little Spirou”). Though I have not had the chance to read this spin-off series, it frankly sounds a bit strange to me. Despite the fact that the basic conceit of the series is to imagine Spirou’s childhood, the mischievous (and even a bit skirt-chasing) young Spirou has virtually nothing in common with his adult form other than appearance.

Back in the main series, the Tome and Janry stories developed a bite to them. In time, they began to stretch the comic to its limits, making use of unusual storytelling techniques and putting the characters in odd new situations. In 1998, they released Machine qui rêve (“Dreaming Machine”), which was heavily criticized for being dark and feeling almost like a different comic than the traditional Spirou and Fantasio comics. The writer and illustrator decided to bow out from the series, instead focusing on Young Spirou.

Since then, the comic has struggled to regain the quality and widespread appeal it had in either its golden era under Franquin or its silver era under Tome and Janry. Authors and illustrators have tried their best, but none have helmed the series for more than five titles. To their credit, the publishers have embraced this reality, introducing Spirou and Fantasio by …, a series that allows writers and artists to try out one or two albums, sometimes radically re-imagining them. This has had varying success (I find the works of the team of Yan and Dany, for instance, to be a bit distasteful.)

In the summer of 2022, the most recent album, La Mort de Spirou (“The Death of Spirou”), was just released. It is the first in a multi-part story by a new team, and, as with so many long-lasting properties, the rights-holders have apparently decided that the best way to drum up interest in their products is to kill off a beloved character. Color me skeptical, but since the album has yet to be translated, I have not read it and may be falling into unnecessary cynicism. Hopefully the story represents a return to form for the series—and hopefully the death, like so many comic book demises, is only temporary.

But let’s turn back to Spirou and Fantasio’s golden age, the work of Franquin. Readers who, like me, grew up with Tintin and Asterix will find much to enjoy in these comic albums. Each one tells a relatively self-contained tale of Spirou and Fantasio’s adventures. Each story is a whirlwind of fun. The situations are imaginative. The characters, though often comedic, are realistic in their larger-than-life way. The art (drawn in the ligne claire style first pioneered by Tintin’s Hergé) pulls readers into its wonderful cartoon world.

I chose the adjective “wonderful” intentionally. As I mentioned at the beginning of this article, I never had the chance to read Franquin’s Spirou and Fantasio as a child, instead discovering it as an adult. It can be easy to fall into pessimism and cynicism in adulthood; I am far more aware today of the many problems facing our world and of my own personal failings. But reading Spirou and Fantasio presents a kind of escapism that lifts my spirits. It takes me out of the daily trials of life and pulls me into these tales where, no matter the danger, Spirou and Fantasio will triumph with aplomb.

But what goes on in Franquin’s stories? Generally speaking, the two protagonists find themselves or one of their friends in some kind of difficulty (their animal friend the Marsupilami is kidnapped, say, or someone who looks exactly like Fantasio is committing crimes), and they have to solve the problem. They are often helped by the Count of Champignac, a figure with Einstein hair who is constantly developing fantastical new inventions. These inventions are often highly imaginative, and it is great fun to see how they are used throughout the stories. The female reporter Seccotine (“Cellophine” in the Cinebook translation) makes occasional appearances and steals the show when she does. Fantasio’s rivalry with her is hilarious, and it’s hard not to wish she were a more regular part of the team, having appeared in only a handful of Franquin’s comic albums.

The conflicts in some of the stories are caused by the protagonists’ actions or those of their friends, as when the Count discovers a preserved dinosaur egg frozen in the tundra and hatches it, leading to the wild situation of a dinosaur stomping around a small French town. In some of my favorite albums, though, Spirou and Fantasio have to thwart the machinations of villains, most famously Fantasio’s conniving cousin Zantafio and the mad scientist Zorglub. (Why the two biggest baddies’ names both start with Z, I don’t know.) Perhaps the best story yet published in English is The Dictator and the Mushroom. In this tale, Spirou and Fantasio end up prisoners in a South American banana republic being run by Zantafio. There’s some excellent soft political satire throughout, and Zantafio’s attempts at invasive war are continually foiled by the two heroes.

Thus far, Cinebook has released about half of Franquin’s albums. Understandably given the series’ relative obscurity, the company decided to publish the most popular and accessible albums first, including albums from a mix of different authors. This means, though, that some early albums (including those introducing Zantafio, the Count, and the Marsupilami) are not yet accessible in English. This is a shame, since completionists like me prefer to read this sort of series in order, but each story is complete in itself, so little is lost by reading them out of order. (That being said, my own bookshelf has them sorted in order of their French release, rather than the numbering of the English editions.)

Franquin’s Spirou and Fantasio is a joyful series that I can heartily recommend to readers, and Cinebook is doing the Anglosphere a real service by releasing these great stories in English. As I said before, they provide ample opportunities for a kind of healthy escape from the dreary mundanities and difficult challenges of the contemporary world. In making this point, I am not using “escapism” derogatorily. It has been noted before me that those who most oppose escape are jailers, and the modern world is rife with them. J.R.R. Tolkien, though speaking of the perhaps more refined topic of fairy stories, made a point that I think is applicable to these wonderful comics:

I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which “Escape” is now so often used: a tone for which the uses of the word outside literary criticism give no warrant at all. In what the misusers are fond of calling Real Life, Escape is evidently as a rule very practical, and may even be heroic. … Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it.

By entering into the escapism of Franquin’s comics, I hope you can re-enter the everyday world with just a bit more joy and wonder than you had before. Happy reading.