There is great value in literary restraint. Consider that some of the most beloved story concepts are tightly constrained. Jane Austen’s novels, for instance, are masterful examples of comedies of manners, and they need not stray into science fiction or explicitly political topics to remain of interest to readers. On the other hand, there are other revered stories that very open-ended: Mark Twain’s series of books about Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn include light tales of childhood adventure, an adventure story that confronts slavery, and a little-known detective novel.

Many comedic newspaper comics fall into the first category, having a straightforward setup: a husband and wife lovingly bicker; a cat tries to sleep and eat as much as he can; a teenager is perennially misunderstood by his parents. Having a small scope is by no means a deterrent to greatness. (Krazy Kat, for instance,is universally considered one of the greatest comics of all time, and it had an astonishingly simple—if surreal—premise for decades: a cat is in love with a mouse, and the mouse throws bricks at the cat’s head.) However, when it comes to adventure comic strips, being open-ended is often a virtue, and this is certainly true for this article’s subject, Alley Oop.

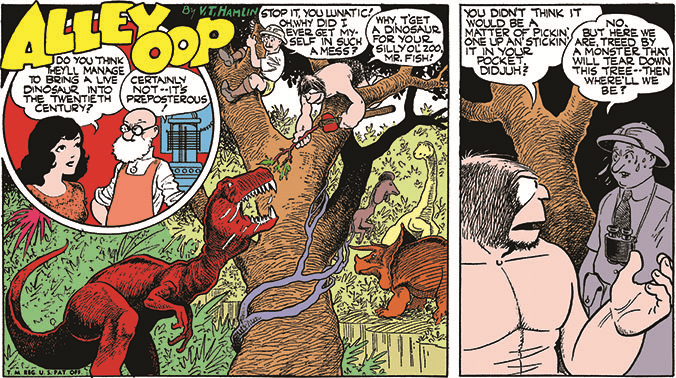

Alley Oop portrays the exploits of a time-traveling caveman (yes, you read that correctly). The comic, which has been running since 1932, was created by V.T. Hamlin. While most Alley Oop comics have not been reprinted since their initial publication, the independent publisher Acoustic Learning has recently begun releasing books with the aim of covering the entirety of the strip’s first seven decades.

Given its longevity and variety of storylines, it would be a fool’s errand to attempt to speak about the whole of Alley Oop. Thus, this article focuses on the Sunday strips from the early decades of the strip’s history, particularly those from 1939 to 1944 and recently collected by Acoustic Learning. These Sunday strips present readers with scenes including ancient Egypt and the Trojan War, fights with pirates on the high seas, and armored knights in castles. Because of their sheer variety, these strips by V.T. Hamlin showcase much of what made the twentieth-century American adventure comic so beloved.

Before discussing Alley Oop, it is best to begin with its architect, Vincent Trout Hamlin, who was born in 1900 in Perry, Iowa. That small city then had just under 4,000 residents, and it nurtured the young Hamlin well. He enjoyed comics from a young age, reading them in his local paper. He loved the work of A.D. Condo, whose black-and-white comedic drawing would influence the composition of Alley Oop, particularly the strip’s character design. (In fact, in an homage to Condo’s work, Hamlin used two of Condo’s characters in a series of strips that were published in 1969!)

Another of Hamlin’s favorite cartoonists was Winsor McCay, whose seminal Little Nemo in Slumberland (1905-14 and 1924-27) captivates readers and influences artists to this day. The comic’s panoramic, psychedelic images greatly influenced Hamlin, and the dinosaurs that occasionally appeared would have stylistic echoes in Hamlin’s own work several decades later. That same animal was the subject of one of McCay’s most famous creations, 1914’s Gertie the Dinosaur, one of the first-ever (partially) animated films.

An artistic child, Hamlin drew his own cartoonish characters. And, as a teenager, he provided drawings for his school’s yearbook and newspaper. This gave him vital early experience, but his budding creative endeavors were cut short when, like many of his contemporaries, he lied about his age in order to enter the army during World War I. After an injury from poison gas forced him to recover away from the front lines, Hamlin began providing illustrations for the letters his army buddies were sending home. A newspaperman saw some of his work and suggested that he might make a living by providing illustrations for papers, an idea that attracted Hamlin.

Despite never graduating from high school, Hamlin was able to enroll as an undergraduate student, first at the University of Missouri and then at Drake University, which was much closer to home. He enjoyed some of his courses, but he lost any passion for studies when, in a drawing class, one of his professors held up one of his drawings and publicly shamed him for his career ambitions. Sources disagree on the precise wording, but one claims that the professor said, “Now here’s a man with a wonderful talent and he wants to waste it on being a cartoonist.” Hamlin recalled, “When she gave me my tiger back, I proceeded to paint on a top hat, put spats on his feet, a cigar in his mouth and a cane in the crook of his tail. After that, I was out.”

While a college student, Hamlin began working for the Des Moines Register, and he found his duties at the newspaper so much more to his liking than scholastic pursuits that he soon dropped out of school. However, fate seemed against him, as Hamlin lost his job and then spent eight years doing various jobs around the country, hoping to find a career that would both satisfy him and pay the bills.

This is where Hamlin’s most famous creation comes into the story. While Hamlin drew the first image of the caveman who would become Alley Oop when he was only a boy, the comic wouldn’t come together until his early thirties. After marrying his high school sweetheart and moving to Texas, he began providing illustrations for Texas Oil World, a periodical aimed at members of the oil industry. While doing research for this job, Hamlin was struck by the idea that the oil powering our lives was the remnants of dinosaurs. He began to imagine what would have happened if dinosaurs and human beings co-existed, and thus Alley Oop was born.

Alley Oop began in 1932 as a daily comic strip, with the Sunday page being added two years later. For the first seven years, stories took place entirely in Moo, a fictional “Bone Age” land where dinosaurs and people mingled. The protagonist, Alley Oop, looks like a stereotypical caveman, with huge muscles, a square jaw, and a hairy face and head. Though readers might expect this caveman to be a dullard, he actually shows great ingenuity and insight, often getting into jams and finding clever ways out of them.

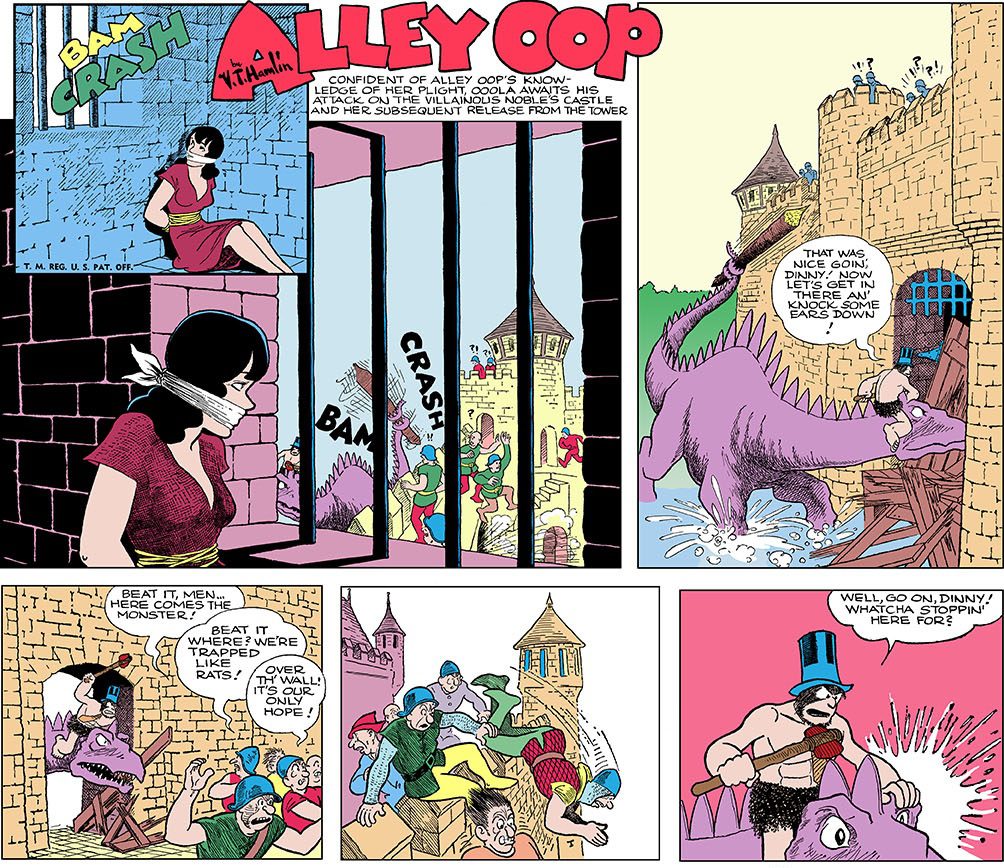

These early, Bone Age stories are peopled with colorful caveman characters, as Hamlin developed a whole social and political order for the Land of Moo. Alley works as an assistant to King Guzzle, which allowed early strips to make gentle political satire. The early strips also engage in some social satire, largely springing from Alley’s relationship with Ooola, a beautiful young Moovian lady. Perhaps Alley’s most iconic relationship at this time, though, was with Dinny, a dinosaur that he domesticated in the opening weeks of the daily strip. All in all, the early strips told fairly straightforward stories about caveman life with dinosaurs, albeit very enjoyable ones.

In April of 1939, though, Alley Oop permanently changed—for the better, to my mind. Alley and Ooola were suddenly transported to the modern-day laboratory of Dr. Elbert Wonmug, the inventor of the world’s first functioning time machine. Soon, Alley begins traveling throughout time, often accompanied by Ooola, who often shows herself to be more than a damsel in distress (though she can play that role too). Alley and his various companions adventure and get into scrapes across the ancient world, the middle ages, and modern times. These time travel stories are where the fun really begins.

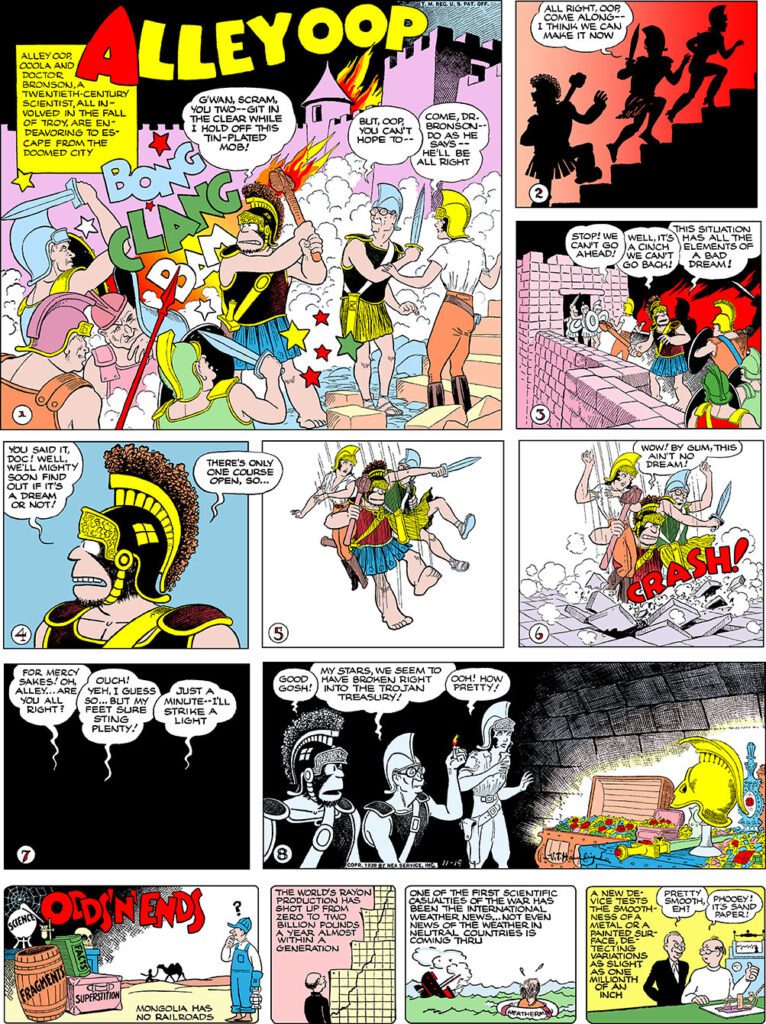

The ’30s and ’40s were unequivocally the golden age of the newspaper adventure strip. It was in these decades that Alex Raymond brought readers to far off planets in Flash Gordon, Roy Crane hit his stride with Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy, Hal Foster dazzled with Tarzan and Prince Valiant, and Milton Caniff premiered not just one but two legendary strips in Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon. These strips, like Alley Oop,began publication in a time when Sunday comics in the United States were given a massive amount of space every week for their characters’ adventures to fill. Each Alley Oop strip took up an entire page of a newspaper, measuring 24 inches by 32 inches. Today, this would be unthinkable, but in those days the Sunday comics pages were a huge driver of sales for papers, and Hamlin made unforgettable use of his playground.

To my mind, what sets Alley Oop’s role on the Sunday pages apart is the sheer variety of its adventure tales. In the first few years of time-travel adventures, Alley fights with pirates on the high seas, meets Cleopatra, becomes a knight in the middle ages, and even tries to do his part for the war effort during World War II!

Given the size of classic Alley Oop strips, Hamlin often presents the more dramatic parts of the caveman’s exploits in massive panels. Take, for instance, the strip from November 19, 1939: Alley Oop, and friends have traveled to the Fall of Troy.

Surveying the size and scope of a single Alley Oop strip for the ’30s, it’s obvious that publishing these classic strips poses a challenge. The publisher Dark Horse began a series of reprints of the Sunday strips in 2014, but they only released two books before ending the series. Thankfully, a lifelong Oop fan named Chris Aruffo negotiated for reprint rights. The press he founded, Acoustic Learning, has been putting out the books at a breakneck speed. In just a few years, he’s released over 40 years of daily strips and around a decade of the Sunday strips. This has required a staggering amount of restoration, especially for the early strips. For those interested in learning more, Aruffo wrote a three-part series on the process, and the third part in particular shows the work put into the Sunday strips. The volumes of the oldest strips are a thing to behold: at 12 inches wide and 16 inches tall, they allow readers to enter fully into Hamlin’s lush artwork.

The variety of these adventures kept children and adults alike excited for each week’s installment, and they make the comic feel evergreen to new readers. Hamlin’s inspiration was the whole of human history, meaning Alley’s adventures are limited only by his author’s imagination. This last point is crucial, as Hamlin’s aim was not to depict everything with perfect historical accuracy. Instead, he aimed to feed the imagination, using historical events as backdrops for Alley’s adventures.

Alley Oop’s relationship to real, flesh-and-blood history matters, because it is one that the contemporary mind could easily misunderstand. If Alley Oop is judged merely as some kind of pedagogical text for the imparting of cold, historical fact into the minds of readers, there are better history textbooks available. But its purposes are different and, dare I suggest, more important than that.

The joy of the time-travel story is not to teach history as a textbook would, with facts and figures marshaled as evidence. Instead, the joy arises from entering into a world unlike our own. This does not mean that works dealing with other times cannot be interested in presenting such facts. But such an instructive function is, in a way, not the real gift of time-travel stories. In previous columns, I have indicated how the medium of comics has a special relationship to wonder, and this is also true of the time-travel story. Alley Oop, being a comic strip about time travel, is one of the best illustrations of each of these relationships I know. With each storyline, readers are thrust into a new time and place and encouraged to imagine themselves there. Even though they are often rendered in a simplistic way, each historical moment is depicted as deserving our attention.

This has moral import as well as imaginative significance. It is easy to feel as though the moment in which we live is the pinnacle of all human existence, the still point against which all other times should be judged. But time travel stories like Alley Oop remind us that human history is a great tapestry depicting almost countless expressions of human nature. These fantastical stories are a joy to read, yes, but they are more than that, for our virtues and our vices, our genius and our folly, are all beautifully illustrated in the sprawling Sunday pages of Alley Oop.