The comic is, as I have previously argued, a unique medium and an art form that deserves serious attention. The integration of verbal narrative with visual storytelling results in works with a power and flair all their own. That being said, it can be easy, when writing about individual works in the medium, to speak extensively about the plots and characters and give little attention to the art. This central aspect of the medium’s appeal can almost go unmentioned even during lengthy discussions.

This is not the case for Blake and Mortimer, the long running bande-desinée series first written and illustrated by Edgar P. Jacobs and now available in English from Cinebook. This series, which focuses on the adventures of the daring duo of Francis Blake and Phillip J. Mortimer, has a feeling, a style, all its own. This style is, of course, in part thanks to its distinctive use of words, but far more crucial is the penciling and coloring. Jacobs (and, to a lesser extent, the artists who followed him) crafts fully fleshed-out worlds that draw readers in, making us sad to leave at the end of each work.

Edgard Félix Pierre Jacobs, better known by his pen name Edgar P. Jacobs, was born in Brussels in 1904. Drawn to the arts from a young age, he had a great love of opera. He swore to himself that he would never take an office job. Jacobs performed in opera and plays, but he struggled to make ends meet and thus took jobs doing other work for the theater, particularly designing sets. When the Nazis banned comics produced in the United States, Jacobs took a job continuing Alex Raymond’s science fiction epic Flash Gordon, though this task only lasted a few weeks. The magazine that published it then commissioned an original science fiction story, Le Rayon U (published in English last month as The U Ray). Aping adventure titles like Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant and Raymond’s Flash Gordon, Le Rayon U was modestly popular, and it showed that Jacobs had a certain flair for the medium.

The most popular bande-desinée, Tintin, was then being adapted into a play. The story Cigars of the Pharaoh was chosen as the basis for the performance, and Jacobs was hired to help design the sets. His work on the Arabian- and Indian-inspired sets impressed Tintin’s author, Hergé, and he eventually hired Jacobs to assist him in his work on Tintin.

Jacobs helped provide colors for the Tintin story The Shooting Star. At that time Hergé was in the process of colorizing old black and white Tintin albums, and Jacobs assisted with this task for Tintin in the Congo, Tintin in America, King Ottokar’s Sceptre, and The Blue Lotus. This gave him the opportunity to hone skills he would later use on Blake and Mortimer, but most important was his work on the two-volume epic The Seven Crystal Balls and Prisoners of the Sun. For this story, Jacobs assisted Hergé with both drawing and writing, and astute readers can see Jacobs’ fingerprints on the two albums.

At the same time as he was working on Prisoners of the Sun, Jacobs began to write and draw the first Blake and Mortimer story, The Secret of the Swordfish. There, readers are introduced to Captain Francis Blake of the British intelligence agency M15 and his best friend and flatmate Philip J. Mortimer, a professor of physics. The two Brits live in London, but they travel throughout the world over the course of their adventures. Despite the series’ name, Mortimer is really the protagonist of the series, and Jacobs’ stories tend to focus more on scientific speculation than espionage and intrigue, though the latter are certainly present.

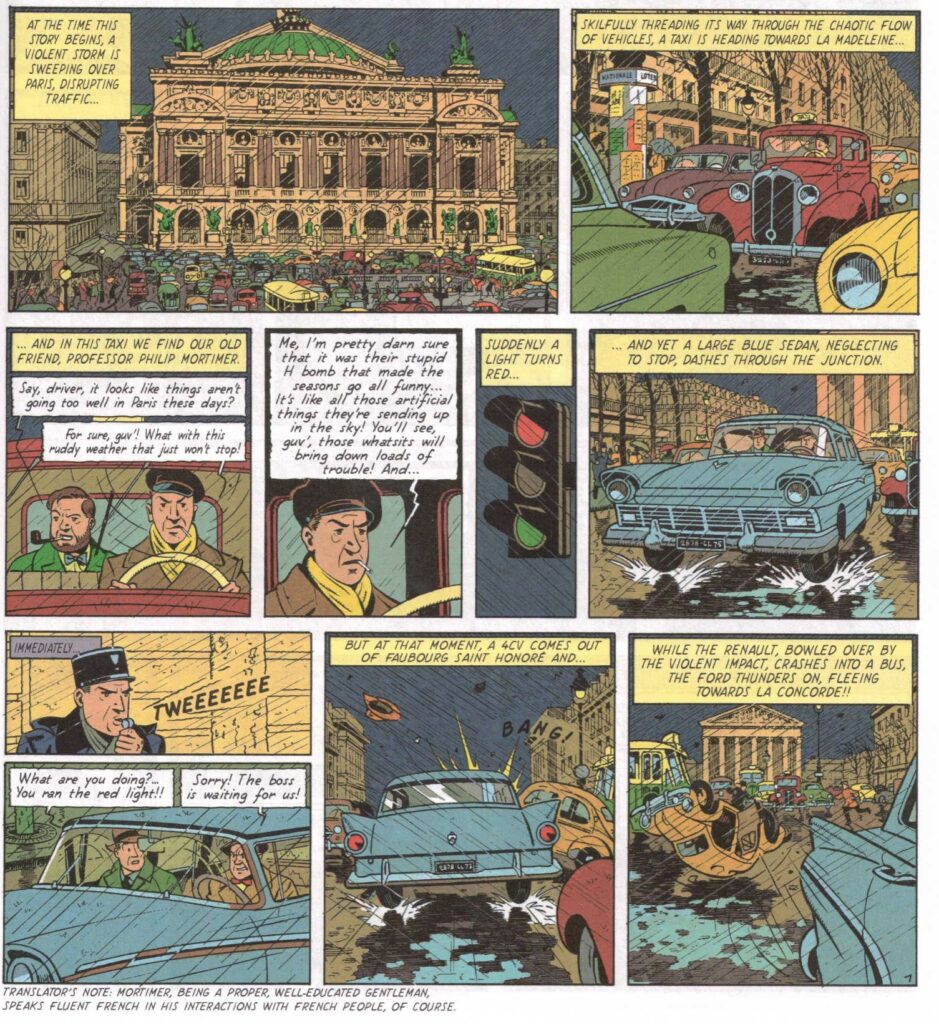

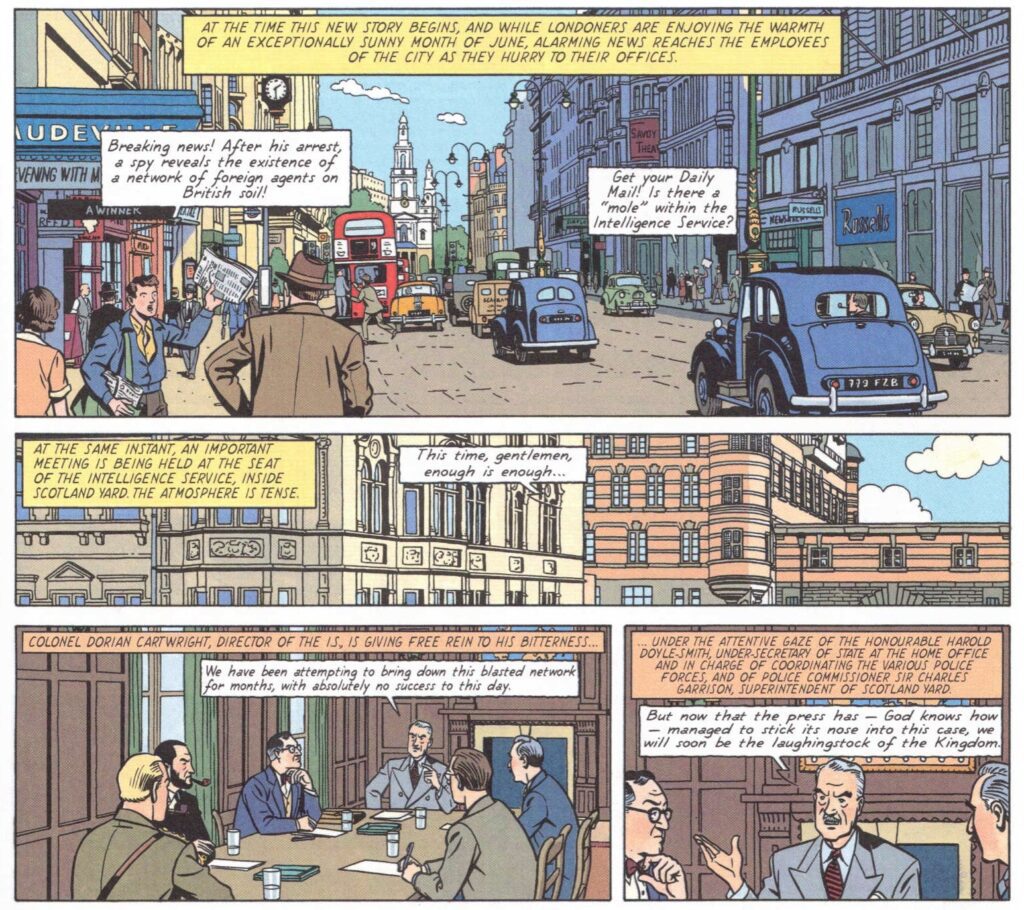

Thematically, the stories touch on ideas of self-sacrificing good versus evil, measured scientific progress, and the value of ordered liberty. The comics are extraordinarily wordy, with constant narration boxes contextualizing (or even just describing) the action depicted and often lengthy dialogue boxes. This allows the themes of a given album to percolate in the back of the reader’s mind throughout the adventure before reaching its conclusion. The final panel of most albums has one of the characters (usually Mortimer) summing up the moral content of the work.

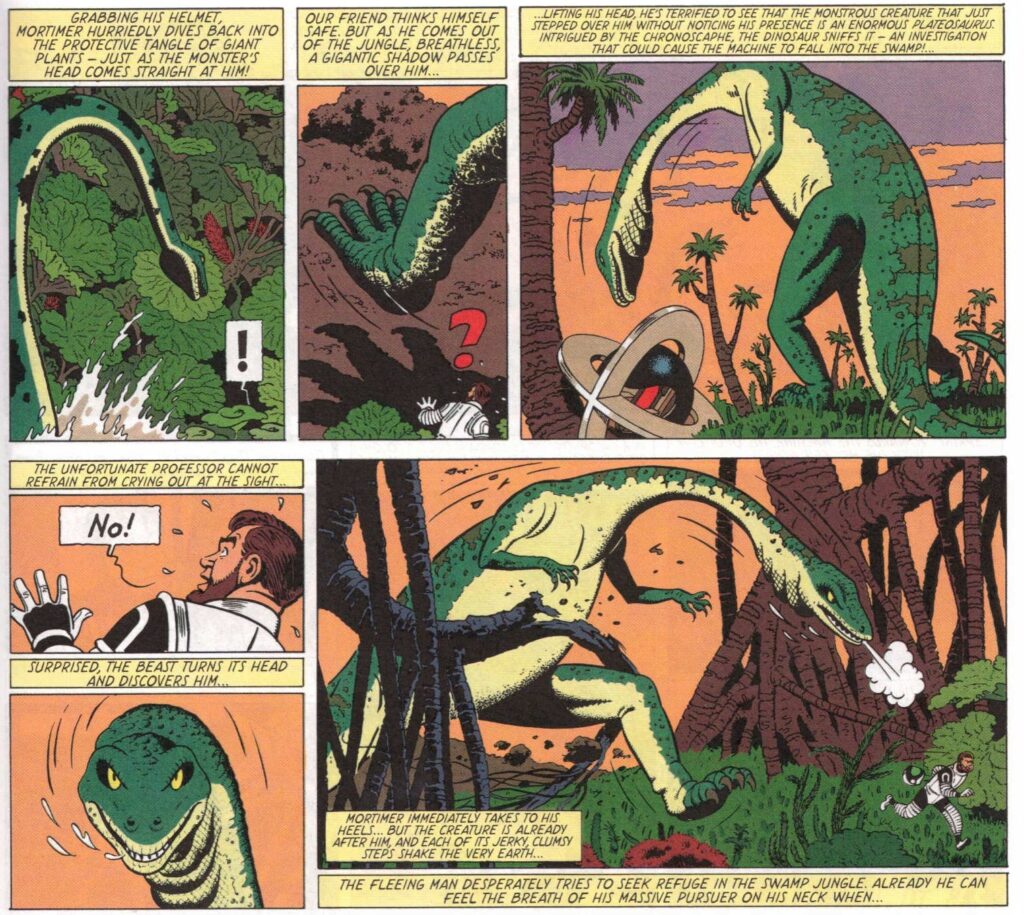

The use of science in the series is worth dwelling on. One of the protagonists is, of course, a physicist, and he often uses his expertise to foil the bad guys’ dastardly plans. There is a distinctly 1950s and ’60s quality to Jacobs’ faith in scientific progress, but he does not think science can solve all mankind’s problems. Like the Tintin albums Jacobs helped script, Blake and Mortimer has elements of the mystical in some of its stories. The rational and the suprarational intertwine, and scientific reasoning is at times humbled by the latter.

To understand the series, it is useful to discuss the first three stories, which take up Blake and Mortimer’s first six albums. The Secret of the Swordfish is an odd first story for the series. It begins with the world in the midst of a cold war between the West and the unfortunately named Asiatic “Yellow Empire.” Early in the tale, the Empire uses its astonishing might to destroy the major cities that threaten its power (an event that somehow never affects later adventures). Mortimer has been involved in designing a weapon known only as the “swordfish” that promises to save Britain and the West. In addition to the Yellow Empire, our heroes are opposed by the villainous Count Olrik, a swarthy man intent on power and destruction who appears in nearly every Blake and Mortimer story.

Swordfish was eventually collected into three albums. (The English editions of the series are released out of publication order, with the most popular albums coming first in order to ensure the translations would be financially viable. Thus, completionist readers want to consult a list of the books’ original chronology when deciding which to read next.) In my view, The Secret of the Swordfish is one of the weakest stories in terms of pacing and technical aspects of storytelling. The story would be much better if it were about half as long, and if readers were given information about the swordfish far earlier and more explicitly. In addition, Jacobs’ famous verbosity damages the reading experience far more in this work than in any other I have read. Only with the third volume does the author really seem to get a handle on his story.

Despite its weaknesses, The Secret of the Swordfish has enthralled readers for decades, bringing them along with Blake and Mortimer for a world-shattering adventure. The work is effective because, first, Jacobs’ art is so engaging and, second, it was clear from the beginning that these characters had great promise. The adventure takes readers around the world, and even though Jacobs would in time become far more proficient at this kind of globetrotting storytelling, this work still stands as a testament to his gifts.

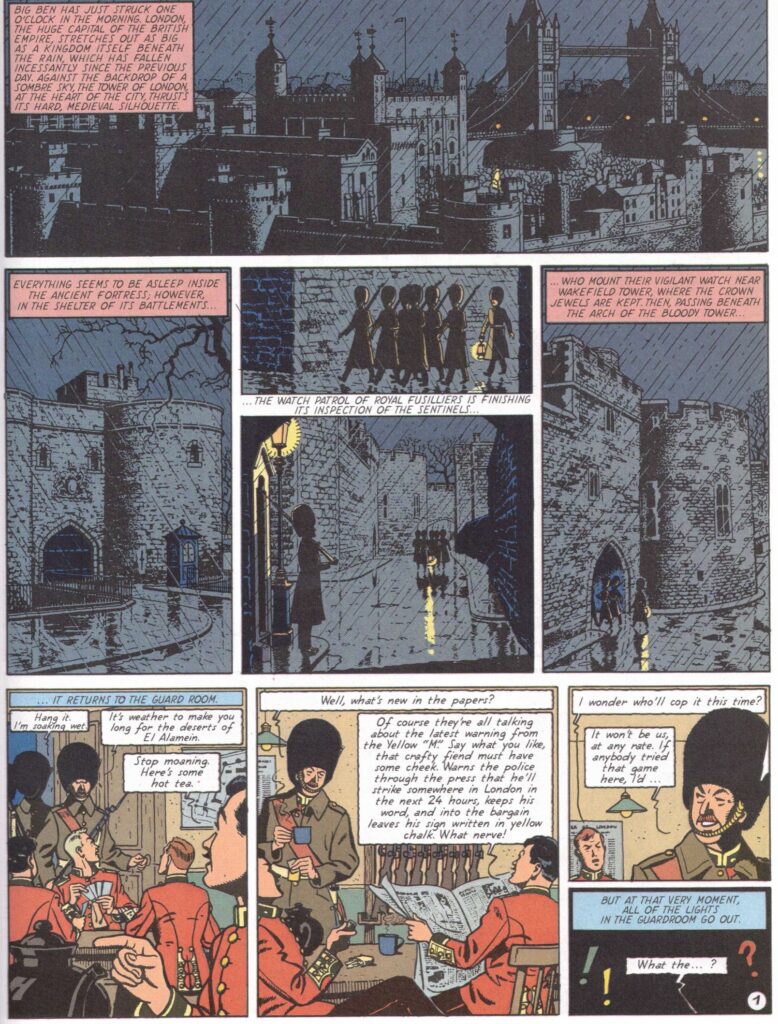

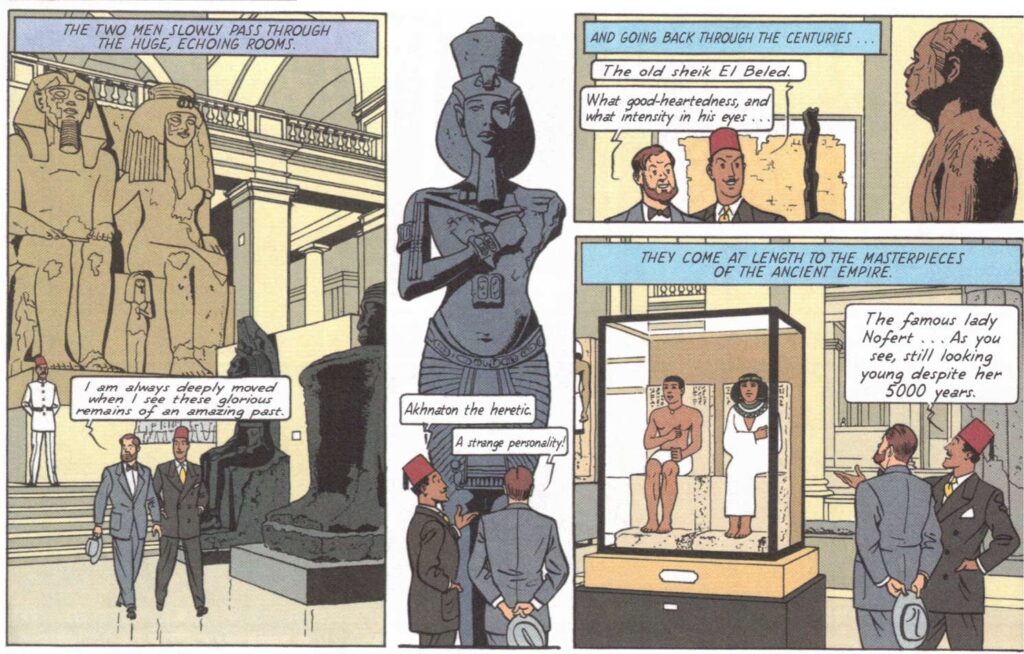

The second and third stories, The Mystery of the Great Pyramid (collected in two albums) and The Yellow M, are where the series really picks up. First-time readers wishing to enter into Jacobs’ works for the first time would, I think, do better to begin here, or with a story like Atlantis Mystery, my personal favorite of Jacobs’ works. The Mystery of the Great Pyramid is a sort of archeological mystery, drawing on ancient Egyptian history and legend. Jacobs’ depiction of Egyptian art and artifacts is captivating. The Yellow M, meanwhile, is a moody, atmospheric crime thriller. A mysterious criminal has been committing high profile robberies, even stealing the Imperial State Crown from the Tower of London! Blake is on the case, with assistance from Mortimer.

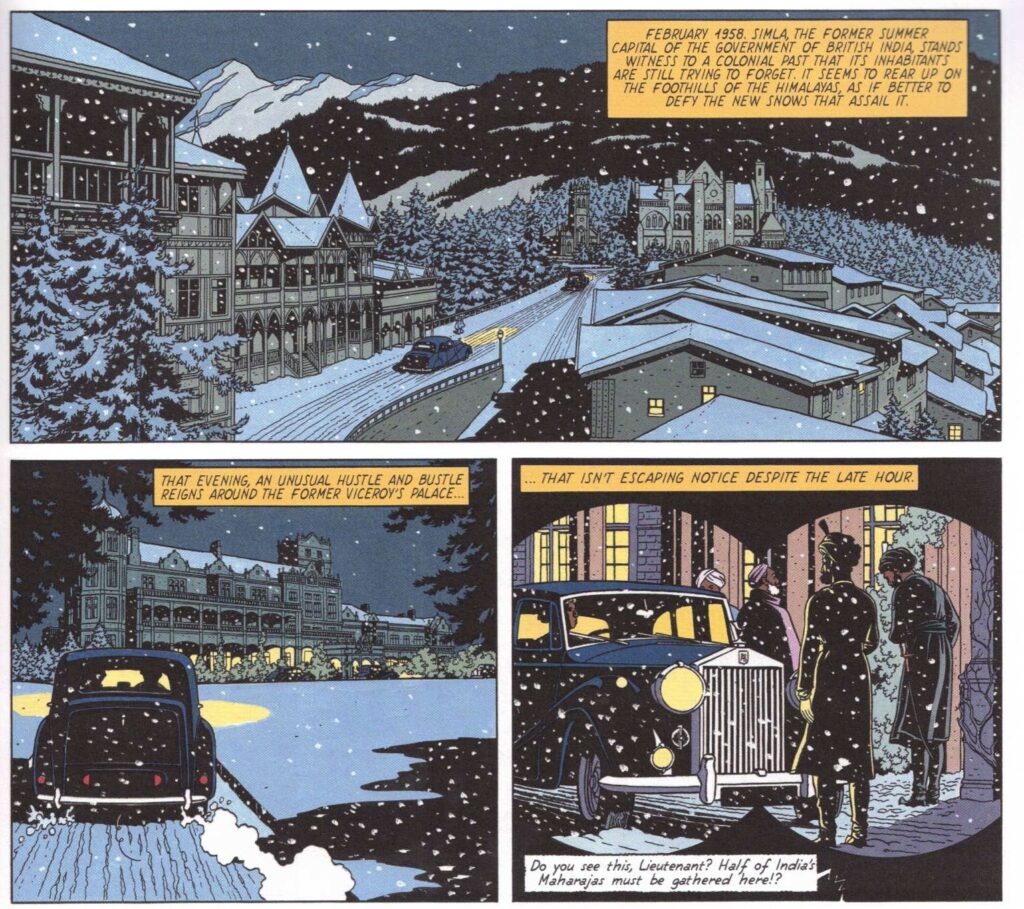

A mere brief description of these first three stories begins to give you a sense of the variety of story Blake and Mortimer tells. This is, I think, its great strength. Each story Jacobs crafted has its own distinctive world. Even those that take place in similar locales somehow feel completely different. The dark, claustrophobic London of The Yellow M feels a continent away from the calm London witnessed at the opening of The Time Trap or the chaotic Paris beset by cataclysmic weather in S.O.S. Meteors. Each story is a world unto itself.

Particularly noteworthy is the comic’s use of color and light. The job of coloring bande-desinée is often handled by assistants, just as in American comics it is almost always performed by someone other than the primary credited artist. Different authors and artists exert different levels of influence on the coloring process, which can occasionally lead to odd coloring choices. However—owing no doubt to his extensive experience as a colorist for Tintin—Jacobs’ works are exquisitely colored. While much of the coloring was presumably done by assistants, my guess is that the author paid very close attention to this important step. Whether depicting the dark blues of a rainy city at night, the rich greens of a forest, or the manifold colors of electronic equipment, the coloring flawlessly draws readers into each situation.

Jacobs worked tirelessly on Blake and Mortimer for a number of years, but at a certain point his pace slowed. In the decade from 1950 to 1959, eight Blake and Mortimer albums were published, while from 1960 to 1977, Jacobs only completed three more, with a script (but no art) for a conclusion to the two-part story he had begun. Upon the author’s death in 1987, it seemed that he had left us with eleven bande-desinée albums of Blake and Mortimer, a script for another, and no hopes of any more.

However, just a few years after Jacobs’ death, something surprising happened: Jacobs’ final story was completed! Bob de Moor, an artist who worked on Tintin for decades, illustrated a thirteenth album. The reception was generally positive, and Jacobs’ estate eventually agreed to allow other writers and artists to continue the series.

The first of these new albums, entitled The Francis Blake Affair, was written by Jean Van Hamme, famous for penning scripts for Thorgal and XIII, while Ted Benoit illustrated the work. Blake and Mortimer fans were divided with regards to the work. While Benoit had captured much of Jacobs’ style, bringing Blake and Mortimer across Great Britain to foil a nefarious plot, some thought that Van Hamme’s writing style did not fit the series. I, however, am firmly in the other camp; The Francis Blake Affair is one of my favoritealbums in the series. Its tight plotting goes well with the espionage-based story, and it is great fun to see the capable but honest Mortimer dealing with the world of double-crossing and spying without the assistance of Blake.

After what many readers saw as a smashing success, there was excitement for the next installment of the series. However, Van Hamme’s schedule was fully booked, and thus another team, writer Yves Sente and artist André Juillard, began working on further stories. These stories are, arguably, closer in content to the original series, having a more scientific bent to them. However, to my mind they are actually better written than many of Jacobs’ works. The characters are given clearer motivations, and their backstories are far more fleshed out. The albums are also more interconnected, and thus they are strongest when read in order. Particularly compelling is the two-part Sarcophagi of the Sixth Continent. This story, which spans not only continents but also decades, tells of Blake and Mortimer’s first meeting as well as Mortimer’s first love. Its depiction of India would make Jacobs proud, and the art feels as though it could be straight out of one of his later works.

Two other writer-artist teams have produced albums, but since their output has been relatively sparse (two books for one team and only a single one for the other), their contributions have been less central to the series. Overall, the Blake and Mortimer stories written after Jacobs’ death have maintained the ability to bring readers into distinctive worlds. Whether James Bond-esque spy-thrillers, adventures in Africa, or science fiction set at the world exhibition of 1958 in Brussels, the authors throw Blake and Mortimer into new adventures with gusto.

I would give one slight caveat to these works, though, since I know that some read this column in hopes of finding recommendations for the young people in their lives. While I would feel comfortable giving Jacobs’ works to any children enthralled by Tintin, some of the albums by other authors have been slightly more mature than earlier parts of the series. The violence is a bit rougher, with blood and even occasional gunshots being clearly depicted. Van Hamme’s The Last Swordfish—a truly excellent follow-up to The Secret of the Swordfish that deepens the original story—is particularly notable for this, including not only some strong violence but even sexual seduction as a plot point. The seduction is, to be clear, extremely tame, with some dialogue throughout the story and just a single panel of two characters in a bedroom—with no nudity—and the clear message of what has just occurred. This is nothing a 16 year-old couldn’t handle, but it isn’t an album I would give as a gift to a 9 year-old nephew in love with the Tintin series.

With that very small caveat having been made, Blake and Mortimer, whether by the inimitable Jacobs or his successors, is a joy to read. Its tales of world travel and crime-fighting are exciting, while its midcentury themes of measured scientific progress and ordered liberty (especially present in Jacobs’ work) provide a bit of depth to some stories. Each album has its own phenomenal style because each album has its own tale to weave. So, the next time you want to foil the plans of evildoers and travel to Egypt, India, or even Atlantis, reach for some Blake and Mortimer. You won’t regret it.