Comics have long been viewed by some as ‘kid’s stuff,’ both in terms of their supposed audience and their intellectual seriousness. While I have previously argued that comics can make excellent reading material for thinking adults, this column has thus far focused on works that are generally appropriate for, and sometimes even aimed at, young people. This is because, in my view, anything worth enjoying over and over again at the age of ten is worth returning to as an adult. However, there are some works of the ‘ninth art’ that are unequivocally aimed at adults, depicting situations and posing questions with which children are simply not ready to engage.

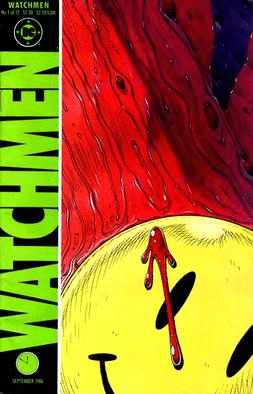

Perhaps no work that falls into this category is as famous as Watchmen, the graphic novel by writer Alan Moore and Artist Dave Gibbons. Taking its title from a translation of a line from the Roman poet Juvenal—“Who watches the watchmen?”—this work deconstructs and interrogates not only the superhero genre but also social and geopolitical life in the 1980s. Though written in a time that was very different from ours, Watchmen rewards careful reading in 2023, a time when films about superheroes hold near hegemonic power over the box office and when the geopolitical landscape looks far from rosy. While the contemporary landscape is full of deconstructive art that generally serves little purpose other than to reinforce progressivism’s cultural hegemony, 1986’s Watchmen represents some of the best of deconstructive art, helping us think more clearly about our world and the art and media we consume.

The characters and world of Watchmen

Watchmen takes place in a world very much like ours but with a slightly different history. Thus, it is helpful to talk a little bit about it before examining the characters and plot. In the world of the book, costumed heroes are real. In the 1930s, after reading superhero comic books, a number of men and women began dressing up to fight crime. Crucially, though, none of them had any kind of superpowers. These vigilantes, with names like Mothman, The Comedian, Nite Owl, and Silk Spectre, were a ragtag bunch. Some genuinely hoped to better the world, but many were in it for money, power, or even the perverse pleasure of doing violence to criminals.

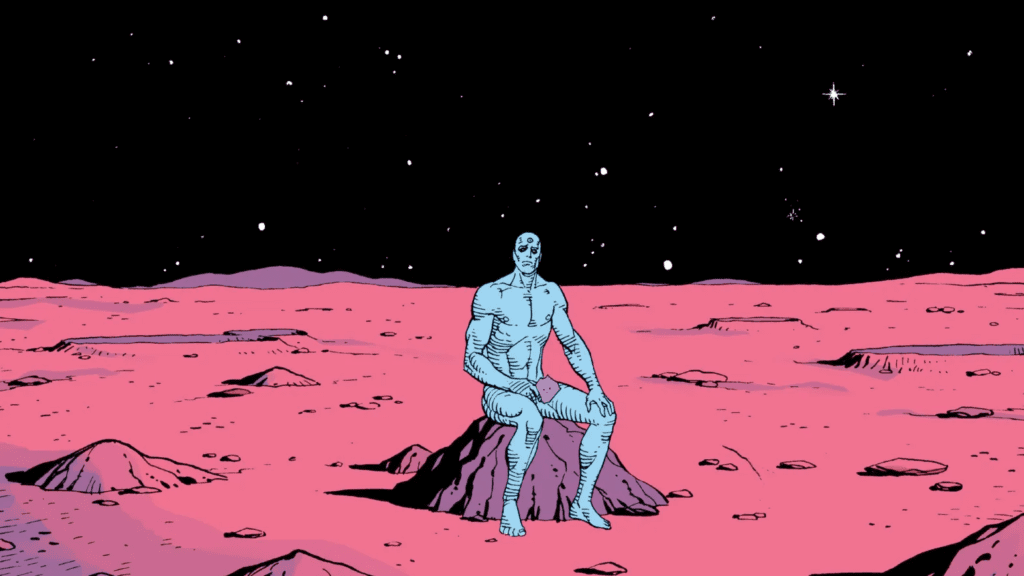

Two decades later, however, a true ‘super’ hero is born. Dr. Jon Osterman, because of a horrible lab accident, becomes the bald, bright-blue, and generally nude Doctor Manhattan. He, unlike any other hero (indeed, unlike any other person in the world), has superpowers. These powers are practically unlimited. Virtually immortal, he experiences all his life as a single instant and is aware of the past and the future as though they were right in front of him. He can exist in multiple places at once, change his size, move objects with his mind, and do almost anything you can think of.

Doctor Manhattan’s arrival on the scene drastically changes, not just the superhero world, but the entire geopolitical landscape. This is where the ‘alternative’ history begins to deviate radically from our own: working for the U.S. government, Doctor Manhattan’s involvement helped ensure that the United States won the Vietnam War. It is left somewhat ambiguous, but it seems that either Doctor Manhattan or fellow government-funded costumed hero The Comedian murdered the reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein in order to prevent the Watergate scandal. This, along with victory in the Vietnam War, gave Nixon astonishing popularity. Nixon thus changed the law to allow the president to remain in office indefinitely, and he is still the nation’s chief when the book begins in 1985.

By the time Watchmen opens, there are only three costumed heroes left fighting crime: Doctor Manhattan, the Comedian, and Rorschach. This is because costumed vigilantism was outlawed in the ’70s after the public lost their affection for heroes. Doctor Manhattan and the Comedian were able to continue plying their trade for the government, while right-wing, anti-government Rorschach simply went underground and continued fighting crime. Doctor Manhattan’s service to the government is the main deterrent to the U.S.S.R.’s warmongering, because no country, no matter how powerful, wants to oppose him.

The book opens with one costumed hero, The Comedian, having just been brutally murdered. Rorschach investigates the murder and becomes convinced that this is the beginning of a plot to take out all costumed heroes, whether currently active or not. He visits all the retired heroes, as well as Doctor Manhattan, to tell them of his suspicions, but he is not taken particularly seriously.

Rorschach is a striking figure. A staunchly principled Randian objectivist, he meticulously journals all his work, passing judgment on the “degenerates,” “criminals,” and “whores.” At the start of the book, the reader is left in the dark about his secret identity, the only character for whom this is the case. While all the characters in Watchmen are in intertextual conversation with earlier superhero comics, Rorschach deserves special consideration. He is something of an homage to the work of Steve Ditko, the co-creator of Spider-Man whose Randian views deeply informed his work. However, Rorschach does not come off as any kind of caricature. Indeed, author Alan Moore’s treatment of Rorschach is one of the aspects of Watchmen that most lifts it above the mass of deconstruction in art.

When I first told a friend of mine that I would be writing a piece on Watchmen—a work he had several times encouraged me to read—he was surprised. He was even more surprised when I said that I had genuinely enjoyed the book. “It seems like a graphic novel version of everything you hate,” he said, somewhat jokingly.

I can understand what he meant.

While the author of Watchmen, Alan Moore, himself has a rather idiosyncratic worldview and unusual politics (he identifies as a magician and an anarchist), his treatment of the character of Rorschach does not feel purely ideological. Indeed, throughout the work, Moore impressively makes each character feel like a full human, one whose views on politics and superheroing are informed by his individual life experience. This attentiveness to character is a big part of what separates Watchmen from much contemporary deconstructive art and media.

Far too often, any fictitious figure who is anything other than a staunch progressive is depicted as some kind of moral degenerate. Perhaps a racist, perhaps a pervert, or maybe just dim, no matter what his problem, being right-wing ensures that a person in contemporary media is sure to be far more a caricature than a real flesh-and-blood character. Right-wingers cannot be anything other than villains in virtually all mainstream media and fiction. Exceptions to this tend to be characters that are only implicitly conservative (e.g., a family man in a television situation comedy or a kindly old woman in a novel) or else are from works released by small, independent entities (such as the recent Sound of Freedom). Other than these relatively rare exceptions, contemporary media, whether obviously deconstructive or not, has a simple presumption: good people are orthodox progressives, and anyone on the Right is clearly inferior.

This is not to say that Rorschach is depicted as a perfect person—far from it. From the beginning of the story to the end, Rorschach is shown to be a profoundly broken man whose way of life has isolated him almost completely from the society he aims to cleanse. However, this brokenness never feels ideological, in large part because every other character in the work is broken too.

Thus far, I have been throwing around the term “deconstruction” without providing any kind of definition. This is an easily-criticized argumentative move, but it is one that I have made intentionally. It seems to me that deconstruction is too wide a phenomenon to be tidily defined a priori. One could easily begin with its philosophical roots in Jacques Derrida (or Heidegger, or Nietzsche, depending on your interpretation of those figures) and discuss contemporary examples of works that maliciously deconstruct aspects of Western civilization with the clear aim of dismantling it.

However, I would like to propose that deconstruction is better understood as an artistic move that pre-exists 20th-century philosophy, or, indeed, modernity itself. For a work of art to be ‘deconstructive,’ it need not be nihilistic or anti-Western, or indeed Western at all. It need only play with and critique that which has come before it in a significant way. Thus, there are works up and down history that have significant deconstructive elements to them.

A good example of what I mean is an epic poem from the 5th-century AD by the Latin poet Prudentius, Psychomachia. This poem depicts a confrontation between personifications of the vices and the virtues. Its author was a Christian who was concerned that pagan poetry, such as Virgil’s Aeneid, encouraged vicious—or at least insufficiently Christian—modes of thought and action. Thus, instead of Achilles killing Hector or Aeneas slaying Turnus, Prudentius depicts Faith beating up Idolatry and Good Works Strangling Greed.

This may not be the most compelling epic poem in the Western canon, but it does, I think, give us a sense of how widely I think we ought to understand deconstruction. ‘Deconstruction’ can be a purely destructive force, as it is in many contemporary works that encourage readers and viewers to engage in anti-hierarchical lives of vice and limitless personal autonomy. However, deconstruction can, in its own way, be constructive. That is to say, while playing with the conventions of an established genre or way of thought, a work can shed light on ways that the world might be better than it is today. To put it simply, there are purely deconstructive works, which are ultimately sterile, and there are works that use deconstruction for a larger positive purpose, works that can bear fruit.

Part of why Watchmen is able to be an example of the latter is that, even though it depicts an astonishingly broken world on the brink of societal collapse (and maybe even apocalypse), the reader is constantly reminded of the ideals of valor and heroism that have motivated the best of the costumed heroes. These ideas of valor and heroism can be covers for abuse of power and other evils, but they are not just that. Oscar Wilde’s Lord Darlington famously described a cynic as “a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.” Moore is certainly an example of the first half of this definition; he works to consider every negative aspect of the idea of superheroes and constantly shows us the underbelly of Western, particularly American, society. But at the same time, he challenges readers to reflect on the values that undergird his criticisms.

Moore does not approach Watchmen as someone who resents superhero comics and wants them to cease to exist. In this way, he is quite different from many of our contemporaries making deconstructive art. A good example of this is what happened to Star Wars after the franchise was sold to Disney.

The original Star Wars films by George Lucas were profoundly informed, not just by traditional works of literature such as the Iliad and Arthurian legend, but also by more modern works like Wagner’s Ring cycle, classic film serials like Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon, and even some of the superhero comics that Moore deconstructs. They make use of Joseph Campbell’s work on mythology in order to craft a work that is profoundly moving, and it can even inspire its viewers to seek virtue.

This is practically the opposite of what many recent Star Wars films and television programs have done, with the most egregious example being Rian Johnson’s Star Wars Episode VIII: The Last Jedi. Virtually every aspect of The Last Jedi patently attempts to tear down what has come before. Luke Skywalker, the protagonist of the original trilogy who spent his films striving for both strength and goodness, is depicted as a pathetic coward. Indeed, every male character is shown to be weak, prideful, and sniveling. The only vaguely heroic characters are the women, who are shown to be almost inherently virtuous and incapable of wrongdoing. The plot is also constructed to subvert viewers’ expectations of what a Star Wars film should be. After watching The Last Jedi, one is left with the sense that the people involved in making it actively disliked, not just the original Star Wars films, but the very civilization and mythical archetypes that birthed them.

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ work on Watchmen has a quite different approach to its inspirations. Indeed, even Gibbons’ excellent art feels far more like Jack Kirby’s and Steve Ditko’s best work from the 1960s than like what has come since. This graphic novel was clearly crafted by two men who share a love of older superhero comics, even as they used it to interrogate the genre and the world that produced it.

Watchmen certainly shines a light on the brokenness of its characters and the society they live in, and although Moore might well agree with the views that inform The Last Jedi, the work itself transcends these views. Just as a reader need not believe in Zeus and Hera to find insight in The Iliad or believe in the Christian God to grow because of an encounter with Dante’s Commedia, so Watchmen entertains and challenges readers in equal measure, regardless of their own beliefs. Watchmen successfully achieves the objectives of fruitful deconstruction, engaging in real critique of its predecessor genres but from a place of genuine respect and appreciation. For this reason, it is one of the most enjoyable and valuable comics of its kind.