As a longtime comic reader, I have known the name of Walt Kelly and his classic strip Pogo for decades. My favorite graphic novelist, Bone’s Jeff Smith, and my favorite comic strip writer-artist, Bill Watterson, each cite Pogo as one of their greatest influences. Indeed, even the local comics legend, Doonsbury’s Garry Trudeau—who was raised just a short drive from the farmhouse where I type these words—is a great fan of Kelly’s work.

Despite these auspicious fans, I never found Pogo appealing as a child. The strip, published from 1948 until the author’s death in 1975, centered around the animal inhabitants of Okefenokee Swamp. It is well-known for its multi-layered humor and cultural and political references, which ensure that the comic initially takes a bit of work to understand. As cartoonist Clay Geerdes put it, “probably only a handful of people, cartoonists among them, understand the many levels Kelly worked on in a single strip. He was to comics what William Faulkner was to the psychological novel.” It is hardly surprising, then, that my ten-year-old self found the comics’ lush drawings and dense, idiosyncratic wordplay difficult to appreciate when I first looked at a Pogo strip.

The invocation of Faulkner is, I think, helpful for approaching Pogo, and I had in fact made that same connection before discovering Geerdes’ comment. Specifically, it is important to know that most of the characters in Okefenokee Swamp speak in their own “Swamp-Speak,” a cartoonized version of rural Southern American English. Thus, like many of Faulkner’s works, readers need to become acclimatized to Pogo’s diction before really coming to appreciate the series’ genius. In addition, the art, though beautiful, is unlike anything a reader is likely to come across on a comics page today.

I recently decided that, given that I write a monthly column on comics for this publication, I really ought to put aside my childhood confusion around Pogo and see if I could come to appreciate the strip. On cracking open the first volume of Fantagraphics’ beautiful hardcover editions of Pogo: The Complete Syndicated Comic Strips, I was immediately enchanted by the art. The real question, though, was this: would I come to appreciate the characters, stories, and idiosyncratic dialogue? To answer briefly: yes, and in spades.

Pogo is a difficult comic strip to describe, in part because it is so different from other strips. As previously mentioned, the first barrier to entry is the characters’ speech patterns. On first encountering it, many people, particularly those for whom English is a second language, find the Swamp-Speak confusing. Spanish-born cartoonist and Pogo fan Sergio Aragones tells—in his forward to the seventh volume of Fantagraphics’ edition—of how, after discovering Pogo, he would ask adults who claimed to speak English if they could translate the comic for him, but none of them could make head or tails of it.

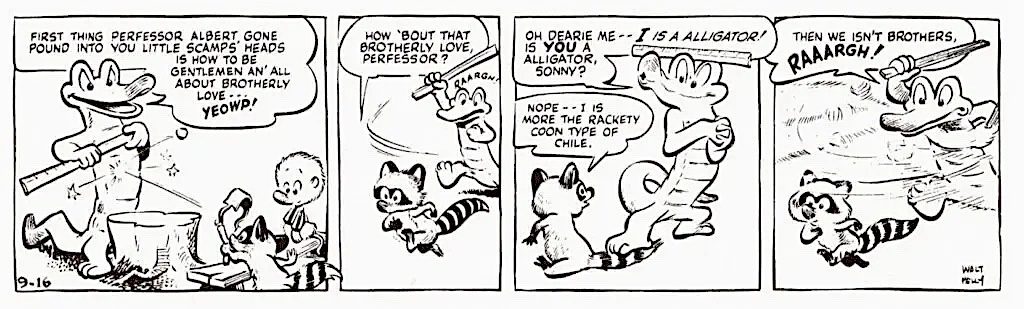

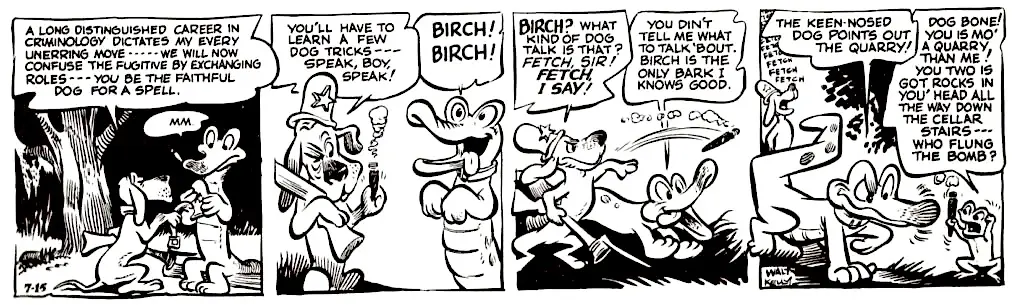

The Swamp-Speak (or, as I prefer, “Swamp Talk”) is an idiosyncratic form of Southern American English that is chock-full of malapropisms and non-standard spellings. (A favorite of mine is “redickledockle” instead of “ridiculous,” but “incredibobble” for “incredible” is pretty fun too.) These verbal oddities were so pervasive in Pogo that future editorial cartoonist Ben Sargent’s aunt wouldn’t let him read the comic as a child because she was worried it would harm his grammar. In reality, Swamp-Speak requires careful attention to grammar and syntax, and I personally find reading it helps cultivate my own awareness of speech. Kelly’s work was deeply influenced by Lewis Carroll, and this is apparent in the wordplay. The Swamp Talk allows for incredible (and incredibly fast) banter and mutual misunderstanding between characters. This is part of why Fantagraphics’ editions are such a joy; each collecting two years’ worth of strips, they allow readers to immerse themselves in Pogo’s unique linguistic patterns and really enter into the fun of the conversation.

Bill Watterson, author of Calvin and Hobbes, said of Pogo’s conversational style, “Unlike a setup and gag, a true back-and-forth conversation makes all the panels funny.” This is one of the most noticeable things that distinguishes Walt Kelly’s work from that of most other daily cartoonists. When reading Pogo, I frequently laugh out loud, but surprisingly it is often at the middle panels, parts usually relegated to mere setup for punchlines in other strips. Watterson particularly praises the “ludicrous conversations of mutual misunderstanding” that can sometimes lead to a laugh a panel. Thankfully, though, not all the humor is high-brow or difficult to understand. As cartoonist Garry Trudeau put it, “Kelly worked on multiple levels, leaving no one out of the fun.”

I discovered soon after beginning to read Pogo as an adult that they are far more enjoyable when read aloud. Despite the fact that I am notorious among my friends for being terrible at accents, I have great fun sitting in my living room reading aloud Pogo’s swamp speak. (And, to back up Trudeau’s claim that the strip is accessible to all, my nine-month-old son giggles at many of the silly sounds coming out of his father’s mouth.) I highly recommend reading these strips aloud. Much of the seeming complexity of the dialogue melts away, leaving you to enjoy the strip’s vocal electricity.

The verbal intricacy is, however, only one part of the strip’s unique character: another is its art. Many fans of Pogo tell of how, as children, they couldn’t understand many of the jokes in the comic, but they would nonetheless stare at the art for ages. Kelly’s distinctive art style was made possible in part because of his use of a paintbrush. His brushstrokes lent a certain distinctness to each figure on the page, allowing the characters to be instantly recognizable. Perhaps the most beautiful fruit of his art, though, is Okefenokee Swamp itself, the setting for the strip. Trees and lakes that, under another artist’s hands, could easily have become mere window dressing, in Kelly’s strip become the perfect backdrop for the characters. This all leads to what Watterson calls the “visual density” of Pogo, which, he observes, requires “a bit of investment” to appreciate properly.

We are quite lucky today to have access to Fantagraphics’ new editions of Pogo, as the full run of the strip has never before been reprinted. Indeed, the first four volumes required impressive detective work in order to track down all the strips, and Kelly’s daughter lovingly and excellently worked to restore many of the early strips, of which we had only imperfect images. This is part of why the series has been released so sporadically. The first volume came out more than a decade ago, and as yet only eight of the projected 12 books have been issued. Thankfully, we have reached a point in the comic’s history where extensive restoration is not required, so the last few volumes have come out at a slightly faster clip. And, while the volumes might seem slightly pricey for the non-collector (around $35-$50 a volume), they are beautifully put-together books with real weight to them that each include two years’ worth of strips, making them well worth the investment. They are clearly designed with great love for Kelly’s life’s work, and as such, they are a genuine pleasure to simply hold in your hands. They are perfect editions for reading aloud to children (or grandchildren), as they will last years of love.

In addition to giving readers access to Walt Kelly’s art, the Fantagraphics series also helps us to appreciate Kelly’s distinctive—and at times esoteric—wit. Each volume boasts a section by R.C. Harvey called “Swamp Talk,” which provides historical and cultural notes for many of the strips. This is particularly useful for younger readers and those outside of the U.S., who are unlikely to have intimate knowledge of the zeitgeist of midcentury America.

With all my talk of Pogo’s intricacies, you might mistakenly get the impression that reading the strip for any length of time feels like some kind of chore, but quite the opposite is true. The stories are an absolute joy. Whether Pogo Possum is trying to learn jazz piano or Albert Alligator is being mistaken for Fidel Castro while dressed as a civil war reenactor, the winding plots pull in any reader. Quoting Calvin and Hobbes’ Bill Watterson again, “Part of [the magic of Pogo] was the rambling storytelling, where every main road to the conclusion was avoided in favor of endless detours … The strip had a mood, a pace, and atmosphere that has not been seen since in comics.” This unique pacing, unlike the strip’s other eccentricities, takes very little getting used to. Any reader can pick up a volume and become invested in the capers of these lovable woodland creatures.

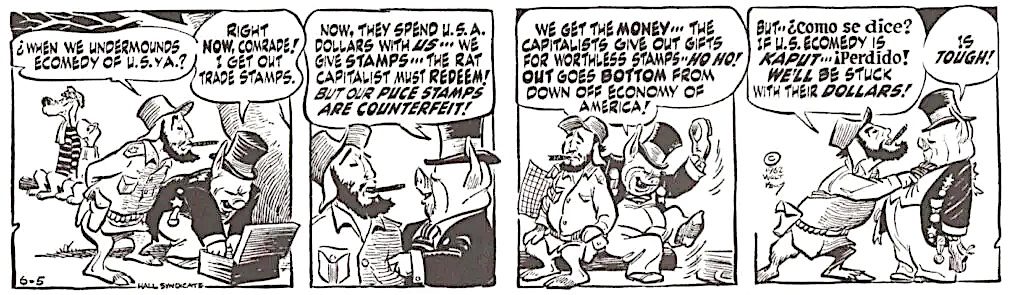

Longtime Pogo fans reading this article will likely be surprised that I have gone this long without discussing one of the strip’s key aspects: politics. Though the vast majority of characters are cute animals, the Okefenokee Swamp is a surprisingly political place. Many people know that Pogo Possum was even a candidate for United States president in 1952 and 1956 under the slogan “I go Pogo” (a play on Eisenhower’s “I like Ike”), but the use of politics goes much deeper. Animals run for office, allude to the news of the day, and try to understand the inscrutable ways of the “gummint” (that is, the “government”). Even many strips that are not explicitly political function as satires of the political events of Pogo’s day.

Walt Kelly was a mid-century American liberal, and his political views informed his most famous work. The political content of the strip reflects everything from Kelly’s skepticism of American warmongering and his disgust with the Ku Klux Klan to his rejection of communism and his care for the environment. The political content occasionally went so far as including caricatures of prominent political figures in the comic, as when, most famously, Senator Joseph McCarthy was satirized as the wildcat “Simple J. Malarkey.” Many newspaper editors were concerned about the political content in the strip. Some proposed moving it to the editorial page, while others went so far as to threaten to remove the strip altogether. As a result, on a few occasions, Kelly wrote alternative strips for editors to print instead of highly political ones. These strips, featuring a cute and innocuous bunny rabbit, are reprinted in the Fantagraphics volumes in addition to those they replaced.)

The passage of time has taken away the bite of some of Kelly’s satire, but other parts concern issues that have become even more partisan. Yet, even when I’m reading strips lampooning groups I am broadly sympathetic with, I don’t really feel attacked. It seems to me that most contemporary political humor—on both sides—fails to accomplish this across-the-aisle appeal. Whether made by leftists like latter-day Stephen Colbert or conservatives like Steven Crowder, contemporary political humor appeals almost exclusively to the political base. Some would argue that this is purely because of the contemporary West’s political polarization, and that is certainly a crucial part of any satisfactory explanation. However, I think there is another piece at play: disregard for art itself.

When a person of any political stripe picks up a book of Pogo comics, he encounters the work of a man who cared about his craft. The art is stellar, characters are fleshed-out, and the wordplay is ingenious. To once again invoke Garry Trudeau, Walt Kelly made it a point not to leave any readers out of the fun, even readers whose views he was lampooning. In many contemporary politically-informed attempts to entertain—whether through comics, films, television shows, YouTube videos, or stand-up—the supposed entertainers are primarily interested only in crafting works that serve purely political purposes. Thus, they all too often leave artistry to the side.

Many contemporary conservatives and libertarians, frustrated by the socially progressive values that inform virtually all mainstream film and television, argue that ‘art shouldn’t be political.’ This, I think, is a deeply misguided position. Aristophanes’ plays challenged ancient Greeks to reconsider their own political realities. Dostoyevsky’s Brothers Karamazov engaged with 19th century Russian political debates. Star Wars was informed by George Lucas’ feelings about American politics in the 1970s and ’80s. Heck, Dante’s Comedy involved placing the author’s partisan rivals in Hell. Politics in art doesn’t get more on the nose than that.

To put it bluntly, I don’t think we ought to object to art—whether comic or not—simply for being informed by political considerations. We ought to object when the politics of a work prevents it from really being art. While Walt Kelly’s work may not soar to the height reached by Dostoyevsky, it is unequivocally a work of art. Pogo’s use of politics complements the other layers of art and satire perfectly. In a world where we are surrounded by bad art made for purely political purposes, Pogo is a breath of fresh air.

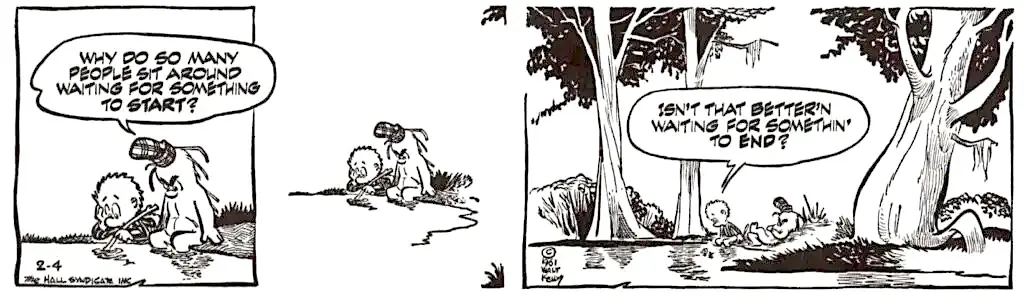

While there is much more that I could say about Walt Kelly and his magnum opus, Pogo, I am in danger of going beyond my allotted article length. Thus, I shall instead content myself with letting Walt Kelly’s characters Porky Pine and Pogo Possum have the last word: