When I was about twelve years old, I began a single-sheet newspaper that I sold to family members, friends, and really anyone I knew who would fork over ten cents. In college, I co-founded a satirical newspaper which (if I may say so) was a clear step up from my childhood ventures. In addition, I began occasionally writing articles for online publications. For my first three years of graduate school, I helped edit a quarterly academic publication. Eventually, these experiences led, in a roundabout way, to my current position as senior editor and regular contributor at this esteemed publication.

One might be forgiven for inferring that I have always had a passion for writing and publishing reporting, essays, and prose writing of all kinds. However, a much deeper passion has existed for much longer: the passion for reading, discussing, and writing about the oft-maligned medium of comics. But what does this passionate interest say about me? Is it little more than a frivolous interest in pop culture ephemera, equivalent to the lawyer who enjoys Hallmark movies or the doctor who treats himself to the latest Michael Bay blockbuster on weekends? Or are comics, as some Francophones argue, a distinct ‘ninth art’?

I have concluded the latter. Comics are an art form that, when practiced well, can help readers to experience stories unique to the medium that challenge them to think more seriously about the world they inhabit. This applies just as much to adults as children, and I hope this article can show some of my reasons why by looking at a few different kinds of comics and considering their virtues.

Comics are a global art form, but in this article I will be limiting my scope to European and American comics. Europe has a proud history producing its own comics. The list is long, with entries from many nations: Germany’s The Digedags, Italy’s Asso di Picche, Poland’s Kapitan Żbik, Serbia’s Zigomar, Spain’s Capitán Trueno, and Sweden’s Bamse: Värladens starkaste björn, to name just some of the best-known.

The Franco-Belgian tradition of cartooning (also known as bandes dessinées), though, may have produced the most culturally significant works which are beloved around the world to this day. This tradition includes such titles as the slice-of-life comedy Gaston, the American-style Western Lucky Luke, the Norse-inspired science fiction adventure Thorgal, the exciting and surprisingly scientific Blake and Mortimer, and the unspeakably over-merchandised (but actually quite good) Smurfs. Francophone culture also has a bit more respect for comics as a medium, evidenced by the fact that five comic series appeared on Le Monde’s 1999 “100 Books of the Century.” I couldn’t hope to provide anything like a systematic discussion of Franco-Belgian comics (let alone all European comics) in a short article, but if we look at the two most famous, Tintin and Asterix, we can begin to see how these comics reward their readers’ attention.

The Belgian cartoonist Hergé began writing and drawing The Adventures of Tintin in the late 1920s. Initially published as part of a weekly children’s supplement to the conservative Catholic paper Le Vingtième Siècle, the comic began by telling stories with clear conservative political undertones. These included stories that were critical of communism, consumerism, and industrialization. Over time, though, the tales became less about politics and more about the fantastic adventures of their young hero, boy reporter Tintin.

For the reader, one of the greatest benefits of these tales is the chance to see the world. Yes, you could easily Google one of the places Tintin visits and see high quality pictures in an instant, but in a time when we are so inundated with such photographs, they have lost much of their power. They become little more than disconnected, meaningless images. Within the context of Tintin, however, we are pulled into a whole world, teeming with its own life. Whether reporting on local politics in Belgium, tracking criminals in China, or meeting the yeti in Tibet, Tintin’s surroundings are compelling and help readers young and old to understand the sheer variety of our world better.

The comics have come under fire at times for their allegedly racist depictions of non-Europeans. With one notable exception, these claims strike me as at best overstated (as in the case of the depiction of Jewish characters) and at worst completely false (as in the case of Chinese characters). While illustrations of non-white characters are not entirely true to life, white characters are hardly photorealistic in Hergé’s signature cartoon style. And while there are, for instance, Asian bad guys, there are far more white villains than anything else. (And here it’s worth noting that one of the main reasons Hergé wanted to publish Tintin in America was to illustrate some of the ways in which white Americans abused their native neighbors.) More importantly, though, Tintin repeatedly befriends upstanding, selfless non-Europeans who are portrayed as full human beings with their own lives and motivations. Indeed, Hergé himself was deeply influenced by a close Chinese friend of his who, in addition to helping him think more deeply about the comic medium, introduced him to Chinese traditions of art that profoundly impacted the Tintin series.

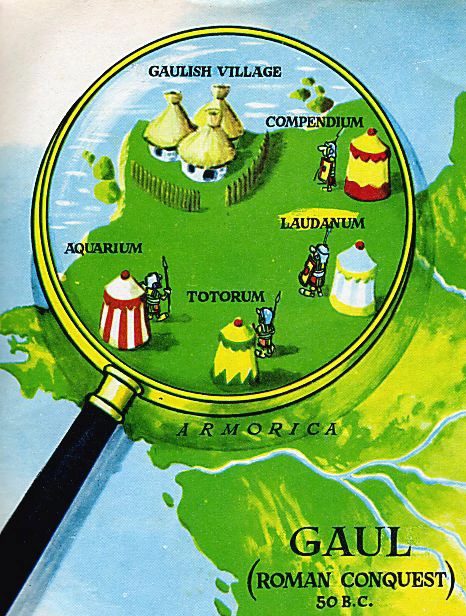

The Adventures of Asterix is quite another story, though it is just as worthy of our time. Taking place in a slightly fictionalized version of the Roman Empire, each comic album begins with a brief introduction: “The year is 50 BC. Gaul is entirely occupied by the Romans. Well, not entirely… One small village of indomitable Gauls still holds out against the invaders. And life is not easy for the Roman legionaries who garrison the fortified camps of Totorum, Aquarium, Laudanum and Compendium…” The titular hero, Asterix, is a very short man who, when he drinks a magic potion, becomes powerful enough to take on any number of enemies. He and his best friend Obelix (who fell into the magic potion as a baby and is thus possessed of incredible innate strength and a robust size), like Tintin, travel around the world, albeit the ancient world, not Tintin’s modern one.

The great difference between Tintin and Asterix, though, is that whereas the first is a series that is deeply concerned with humanizing its characters and secondarily with jokes, Asterix is deeply concerned with being the wittiest thing you’ll ever read. This is not to say that it lacks good characterization, only that this isn’t the main focus. Instead, writer René Goscinny and illustrator Albert Uderzo spent 1959 to 1977 crafting a series of comics (with Uderzo continuing after Goscinny’s death until his retirement in 2009) that will amuse readers of all educational levels. For every silly joke about a man being slapped in the face with a fish, there are five puns working across French, Latin, and English. Indeed, The BBC produced an excellent 20-minute podcast episode in praise of the series’ many puns.

While Tintin is interested in eliciting wonder, Asterix is far more interested in eliciting laughter. Its comedy, unlike much contemporary humor, is generally not tainted by crass sexuality. Instead, many of the jokes pull readers through conversations laced with layers of wordplay that require attention to catch. What has surprised me about Asterix is that, as I have aged, the comic has actually become more amusing rather than less. Far from turning into something I look at as a childish diversion, I see it as a friend that encourages me to fall further in love with not only my own language but also Latin and wordplay in general. The wordplay is exquisitely rendered into English (and many argue it is even improved by the translation at times) by the inimitable Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge. (Unfortunately, American distribution rights were bought by the company Papercutz, and their translation by Joe Johnson, though an admirable effort, is ultimately a comedic failure that downplays much of the comic’s most intelligent humor, so be sure to pick up the British Bell/Hockridge editions.)

For the sake of argument, dear reader, let us say that I have thus far convinced you. Some European comics are worth returning to as an adult, or even turning to for the first time. But what about that most American comic genre: the superhero comic?

The objections to this genre write themselves. Superhero comics are violent. They are childish. They are too liberal, bowing to wokeism. They’re too conservative, parroting fascist ideas and imagery. They perpetuate ideas of American supremacy on the world stage. They objectify the women, who are nothing more than damsels in distress. They objectify the men, who are all muscle-headed beefcakes. They sensationalize violence. They promote escapism. They cost too much money. They are produced so quickly that the art is cheap and shallow. Et cetera, et cetera.

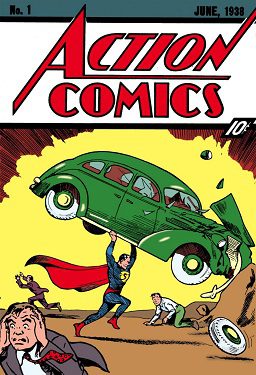

These kinds of arguments can (and have) been multiplied ad nauseum at least since Fredric Wertham published his (in)famous 1954 book, Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youth. This book led to congressional hearing in the United States, public comic book burnings throughout the nation, and the eventual creation of an extremely stringent “Comics Code”—modelled after the Hayes Code for films—that remained in force for decades. Wertham, a psychiatrist who was generally considered politically progressive, noticed that many of the young patients at the mental health clinic where he worked were avid comic book readers. This, in his mind, was enough to convince him that comic books were a prime culprit in causing young people to become delinquents. (The obvious oversight on Dr. Wertham’s part, though, was that around 90 percent of American children aged 8-13 were reading comics at that time, delinquents and valedictorians alike.) Wertham’s foes included comics of all kinds. Perhaps most understandably, he objected to crime and horror works published by EC (“Entertaining Comics”). These comics masterfully employed twist endings and kept readers’ attention, but their sale to young children was certainly questionable. Wertham’s arguments, though, were not focused on advocating simple age restriction, but instead turned into polemic against all comic books. He was surprisingly vitriolic when it came to those comics focused on costumed heroes. For instance, in Batman’s mentorship of his young sidekick Robin, Wertham saw a relationship that was “psychologically homosexual.” As he put it, “only someone ignorant of the fundamentals of psychiatry and of the psychopathology of sex can fail to realize a subtle atmosphere of homoerotism.” And this is besides thinking that Superman was a blatantly Nazi character (despite the character’s having been invented by two Jewish men).

It would take far too long to rebut all imaginable objections to superhero comics, even if I were to limit myself to the most serious (i.e. those not made by Wertham). Besides the amount of time such arguments would take, the more fundamental reason is that I want to focus on how good these stories can be, not just argue that they aren’t as bad as you may think. Thus, I’ll discuss one thing that superhero comics, especially mid-century ones, do admirably: embolden readers to practice the virtues.

Despite the massive variety of superhero comic stories, at the core of many is a simple truth. This truth is perhaps best communicated by Stan’s Lee’s immortal words, which serve as the close of the first appearance of Spider-Man in 1962: “With great power there must also come—great responsibility!” As the twelfth chapter of Luke’s Gospel puts it, of him to whom much is given, much is expected. More theologically said, God’s blessings are not to be hoarded, but instead they are given to us in order that we might give them away. Many of my favorite superhero stories leave readers feeling that they are able to, nay, called to serve others.

If this has the downside of sounding childish and overly-idealistic, it has the simple upside of being true. When demeaning superhero comics, we would do well to remember that one out of every four magazines sent from America to soldiers fighting overseas in the Second World War was a comic book. Many of these told tales of Superman, Captain America, and Batman facing seemingly insurmountable odds and coming out victorious. These stories helped to lift many a young man’s spirits so that he could more easily face the horrors of war with courage.

And courage is far from the only virtue that is inculcated by superhero comic books. Honesty, justice, and self-sacrifice, to name but a few, all take center stage in various tales. Even subversive tales like Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ 1986 Watchmen force readers to confront their pride and the temptation to abuse power—in a word, reminding us of the need for humility. The superhero genre by its nature calls readers to be better today than we were yesterday. It challenges us to grow and care for others, and I for one think we could all use more reading materials that hold us to high ideals.

Thus far, I have done little to explain what makes comics distinctive. The way that some defenders of comics do so is as a sort of pedagogical stepping stone: many children do not want to read a full-length novel, but by luring them in with comics, they end up developing reading habits that they can transfer over to reading ‘real’ books. While it is true that comic books often play this transitional role, this mode of argument actually sells the medium short, making it seem as though the only value comics bring is as a doorway to another medium. Instead of taking this approach, I would like to present an argument from analogy, namely the analogy of opera to comics.

Music is a beautiful thing. It surrounds life within folk cultures, represents some of the greatest achievements of high culture, and even has a prominent place in our ailing time. No one would seriously claim that it is not a distinct art form. Similarly, drama, whether tragedy or comedy, is its own art form with great power. And yet, when they come together in opera, a third kind of art occurs. For many, opera is initially attractive because they are music lovers, while others approach it because of their appreciation for the theater, but once a person comes to experience opera on its own merits, it offers a distinctive beauty and power that its two constituents lack.

Similarly, comics are able to combine visual art with narrative arts. (Not for nothing is ‘graphic novel’ a common term for longer comic works.) Neither reading a novel nor looking at a painting provides us with the same kind of aesthetic experience that comics offer. Whole new avenues of storytelling open up to us when we begin to read comics. Indeed, there are authors and artists who have recognized this—think of Neil Gaiman, who has penned both fantasy novels and many graphic novels, and Bill Watterson, longtime cartoonist who has turned to painting in retirement.

The point that comics are a distinct art form helps explain why it is impossible for me to provide anything approaching a systematic account of the kinds of works available for our enjoyment. It might seem as though this is a reasonable expectation, but let me assure you: it is not. Yes, killer rabbits in medieval marginalia aside, comics may be a fairly young medium, reaching back less than two centuries. But just imagine attempting to write a brief article in defense of sixteenth-century music, seventeenth-century drama, or eighteenth-century opera! There is such variety that you could do little more than make brief, almost random references to a few works in an attempt to provide readers with some sense of the adventure that awaits in discovering comics.

If you have been reading thus far but are skeptical of the value of fantastical stories, perhaps I can interest you in comics and ‘graphic novels’ that are works of nonfiction. Within this genre you can find biographies, like those of composer Glenn Gould, scientist Richard Feynman, or even Pope Saint John Paul II (this last published by superhero giant Marvel). Then there are surprising tales of history like and Marjane Satrapi’s memoir of living through an Islamic revolution Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood or Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, a shockingly powerful work that details the author’s father’s experience as a Polish Jew living through the Holocaust. If this seems too heavy, you might pick up Box Brown’s Tetris: The Games People Play. Or perhaps you are hoping for a much wider view of history, in which case I recommend mathematician Larry Gonick’s monumental and deeply enjoyable (if obviously left-leaning) Cartoon History of the Universe.

Or maybe you are convinced by my case that comics are worth our time but are not interested in reading any long-form works. In that case, I recommend my own gateway-drug: newspaper comics. Calvin and Hobbes, the hand-painted, astonishingly imaginative, and intellectually stimulating comics starring six-year-old Calvin and his (stuffed) pet tiger, Hobbes, should interest any conservative. Then there’s Pogo, which ran from 1948-75 and is currently being released in handsome hardcover editions. This strip is chock-full of great wordplay and political satire. Peanuts, despite its disgusting commercialization, is a beautifully humane strip that constantly grapples with the realities of life in a fallen world.

But perhaps you have been long out of the habit of reading physical books or are on a tight budget. In that case, look no further than webcomics! If you want something intellectually edifying, try XKCD, which boasts jokes about pie charts, quantum mechanics, and teleportation. If that seems too heady, the silliness of Poorly Drawn Lines might be a better fit (here’s my favorite and second favorite). Should you want something halfway between thoughtfulness and utter ridiculousness, Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal, with its jokes about judgmental utilitarians, Voltaire, and Superman tucked into the coziest bed imaginable. Meanwhile, the oddly named comic The Oatmeal has a strip explaining how to use the semicolon that is something of a Bible for me as in my work as a professional editor. The even more oddly named Hark! A Vagrant! boasts the best jokes about literature you’re likely to find this year.

There’s so much more than this to explore. Gareth Hinds’ graphic novel interpretations of classics like the Iliad, the Odyssey, and Beowulf are great ways to enter into these tales, while Boxers and Saints, written by Chinese-American Catholic cartoonist Gene Luen Yang powerfully considers both the Boxer rebellion and the martyrs who died because of it. Carl Barks’ comics from the 1950s starring the Disney character Uncle Scrooge bring the capitalist par excellence to foreign and fantastical locals in search of treasure. On the theme of surprisingly compelling comics about animals, Usagi Yojimbo tells the deeply moving story of a rōnin (masterless samurai) in Japan’s Edo period. And I would be doing you a disservice if I did not recommend what I consider to be the greatest graphic novel of all time, Jeff Smith’s Bone, which begins as the simple tale of three cartoony-brothers who make their way into a beautiful valley and becomes an epic with the scale and power of The Lord of the Rings—but make sure you get the black-and-white version! The art is much more powerful than the colored version, which was published later in hopes of appealing to children. And speaking of The Lord of the Rings, do yourself a favor and spend ten minutes reading Evan Palmer’s adaptation of the first chapter of The Silmarillion, an online comic so beautiful that it convinced me to read the entirety of the famously-difficult work that inspired it—despite having never read any of Tolkien’s works before.

As you can see, just trying to name a few comics makes clear the sheer variety of this medium—and I have only been talking about Western comics! To even begin to get a sense of the myriad forms comics take and the ways their stories can be told, you would want to pick up Scott McCloud’s magisterial graphic novel Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, which is indispensable for anyone wishing to make a serious investigation into the way comics work.

I began this article by asking whether a taste for comics is a pointless and childish pastime or an appreciation of a real and distinct form of art. Above, I have not really provided arguments for the latter position. Instead, I have tried to make my case giving you a sense of the many works in the medium of comics that have impacted my life and the lives of many other readers. I hope that you have at least a taste of the promise of the medium of comics, and in the coming months, The European Conservative will be publishing a series of pieces focusing on a few works of Western comics. However, in order to experience the fulfillment of this art form’s promises and find out whether or not adults should read illustrated books, graphic novels, and comics, you will have to do the easiest thing in the world: pick one up for yourself.