In January of 2011, the British television series Downton Abbey appeared on PBS as part of its Masterpiece Classic series. Depicting the (at times unnecessarily risqué) life and times of the Crowleys, an aristocratic English family, the show was a hit not only in its home country, but also in the United States.

Such popularity may seem odd in America, a country that was forged from the revolutionary fires of Enlightenment liberalism and has prided itself on its separation from the aristocratic system of the Old World.

However, despite their constant protestations of equality and democracy, many Americans have had a fascination with the world of dukes and queens and lords and ladies (as well as pharaohs and sultans and samurai).

Indeed, it might be argued that, through various crazes such as the Downtown Abbey phenomenon as well as earlier fads such as early twentieth century Egyptomania, America frequently experiences the ‘return of the repressed’ desire for a world of hierarchy and aesthetic splendor.

There are, in fact, throughout the United States, entire movements of monarchists, medievalists, and ‘reactionaries’—frequently attached to the Catholic Church as well as among some high church Anglicans that long for a return of the world of ‘throne and altar’ that was almost completely destroyed after the first World War.

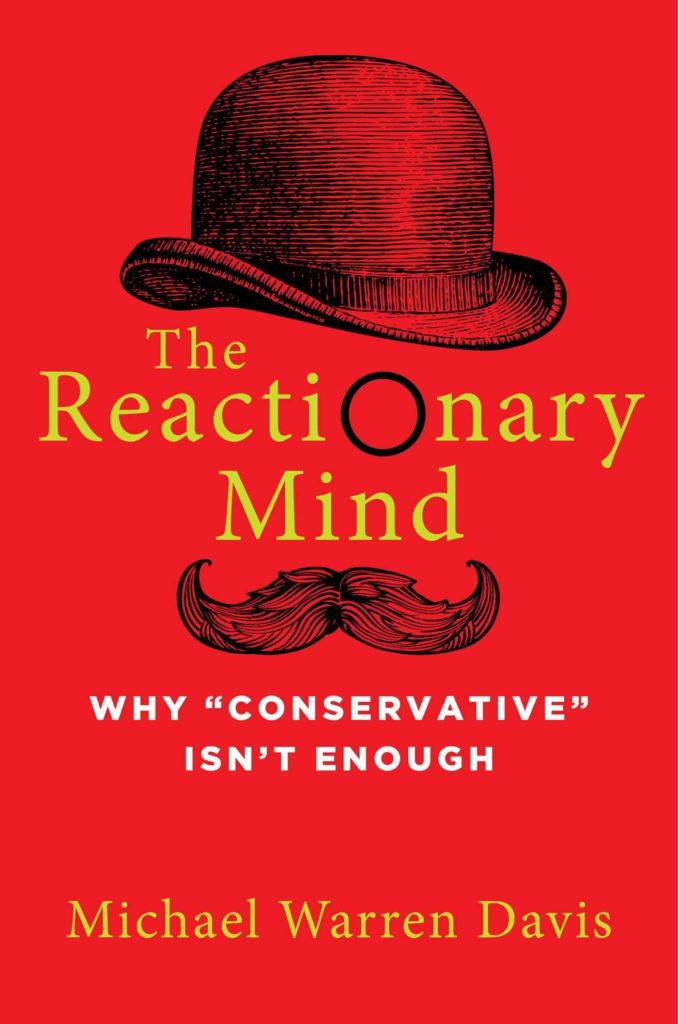

In his recent work, The Reactionary Mind: Why “Conservative” Isn’t Enough, Sophia Institute Press editor Michael Warren Davis presents an argument for Westerners, and Americans especially, to return to (an albeit “tamed”) reactionary lifestyle.

The term ‘reactionary’ generally refers to a counterculture response to the Enlightenment in which an individual or group refuses to embrace some change for which the denizens of progress advocate. These reactionaries, moreover, at times advocate for a radical political change—even including armed resistance to liberal and communist movements.

In contrast, in The Reactionary Mind, Michael Warren Davis, advocates for a lifestyle change more in the tune of Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option, which Davis praises in his own book, as well as other American writers such as Wendell Berry.

Davis does have much praise for the premodern world—especially the Middle Ages, which some Catholics refer to as the ‘Great Age of Faith’ in which the overwhelming majority of Western Europeans were Catholics and lived within feudal and monarchical systems. In his defense of the Middle Ages, Davis presents the arguments—shared by many “secular” scholars of the Medieval Period as well—that very often the medieval peasant was likely freer, happier, and, in at least some cases, better nourished than the current postmodern or postmillennial man.

In The Reactionary Mind, Davis further lays out the reactionary vision of history, which contrary to the ‘Whiggish’ historical narrative embraced by most Westerners, sees the West in a state of basic decline since the Reformation or late Middle Ages. Davis, a proud “Swamp Yankee,” nonetheless notes what he views elements of the American revolution and founding as positive—a point which some of his reactionary Catholic sympathizers would likely contest.

Nonetheless, Davis is principally focused on advocating a lifestyle change in The Reactionary Mind. Like many reactionaries (and, indeed, some radical leftists), Davis shuns social media and smart phones, instead advocating a lives of handicrafts and agriculture among small communities of like-minded people. Davis recognizes that the United States will not embrace a Catholic monarch anytime in the near future, and instead, like J.R.R. Tolkien before him, sees his position as being a (qualified) de facto “anarchist” since he is forced to live outside the superstructure.

Such a position is not necessarily unwise. Many conservatives and traditionalists have paid heavy prices for engaging in the world of politics. However, one might argue that conservatives and traditionalists have no choice but to use peaceful and legal means to advocate a return to traditional values, for the left is in a very totalitarian mood. It does not seem as though conservatives will be allowed to tend their guardians and attend their churches in peace. There must be some sort of political action in the national arena.

Readers might further disagree, as Davis himself admits, with the author’s dismissal of contemporary expressions of masculinity such as weightlifting. Moreover, others might take mild issue with the lists of reactionary books, drinks, and dogs that Davis appends to the end of the book—what makes dogs more ‘reactionary’ than house cats?

Finally, as the Marxist critic Frederic Jameson famously noted, the desire to return to an earlier period is one of the quintessential marks of postmodernism. Jameson is not entirely correct—many people during the Renaissance wanted to return to Classical Greece or Rome—but the literary scholar and critic is right to diagnose that nostalgia is one of the dominant modes of thought in our time.

While Tweed jackets and pipe smoking are elements of the past we might like to preserve, there is a danger of committing the very postmodern faux pas of adopting an image as an identity. The core of what is good about reactionary thought is to be found in the virtues that built the civilization that provided Tweed and tobacco, not necessarily or at least solely the aesthetic.

Moreover, the Edwardian and Victorian periods may have been more ornate and proper than our own; they are, however, in the past. Any attempt re-create them will ultimately fail. We must, in the end, with God’s direction and grace, build a future from the past not in the past.

This nostalgia is not a defect in Davis’s work but rather a benefit. The past is a treasure trove of resources from which we can build and which can ground us in values that might be obscured by the narrowness of postmodernity. However, in addition to re-grounding our lives in nature and faith, we must also struggle to change the world. However, we cannot do this alone—as Davis acknowledges.

Martin Heidegger famously once said in response to the rise of the electronic age and its deleterious effect on the West, “only a god can save us.”

Michael Warren Davis’s solution ultimately is much better: we must re-ground ourselves in authentic human living, but, ultimately, “only God can save us.”