Proudly hanging above my desk is a copy of an article written by a political attaché of the Chinese embassy in Malta, in response to a previous article of mine asking some questions on the initial handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. The original piece submitted by the embassy categorically said that I should be “denounced.” The track record of the People’s Republic of China is such that it would have been worrying if the case had been the opposite!

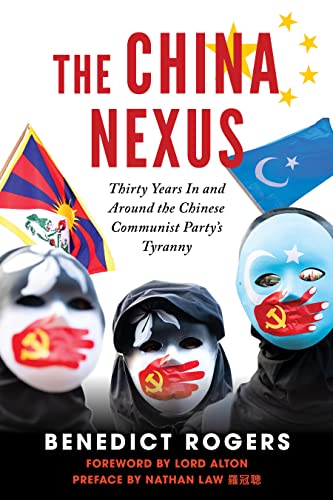

This behaviour seems to be in tandem with China’s style of ‘wolf warrior diplomacy.’ One of the tricks of this aggressive behaviour is to accuse critics of being motivated by racism. Nothing could be further from the truth. In his brilliant book The China Nexus: Thirty Years in and Around the Chinese Communist Party’s Tyranny, Benedict Rogers gives us a good glimpse of just how aggressive this regime is.

At the conclusion of the book, he makes clear: “This is not about being anti-China, or anti-Chinese–but rather anti-authoritarianism … I am deeply pro-China. I love China and its people and culture. It is the brutal regime that represses those people that I love that I detest.” The reader of this book will realise right from the very first pages that the author is passionate about China and angry at what the Xi Jinping regime is doing to this country.

The book opens with the author recalling his experiences as a student teacher in Qingdao. Rogers experiences the kindness of many of his co-workers and newfound friends. This experience instilled in him a lifelong passion for China and the Chinese. These personal connections imbued in the author “a lifelong desire to see the peoples of China free.”

Later, these connections were strengthened when the author worked as a journalist in Hong Kong until 2002. He cautiously explains that, in the initial years, he felt that ‘one country, two systems’ was working well. At first, he did not feel the repression of the Chinese regime. Gradually, however, the situation got worse. Xi Jinping’s stranglehold on power since 2012 began to extinguish any hopes that economic openness would be followed by greater political liberty.

The political crackdown had been coming for a while. The 2008 Beijing Olympics were a catalyst, but the widespread uprisings in the Maghreb and the Middle East seemed to mark a real turning point. This book poignantly marks this descent into greater authoritarianism against the backdrop of the author’s activism. This activism is essential to understanding the book—it gives it credibility and introduces us to different individuals affected by the Xi regime’s retrograde behaviour. Rogers drives home the point that, in addition to the economic, social, and geopolitical concerns, there are human beings who are suffering as a result of lukewarm activity or, worse, benign acquiescence for pragmatic reasons.

The deal signed between the People’s Republic of China and the Holy See is one case in point. Rogers speaks out of love for the Church and faithful Catholics in China.

State-controlled churches had long been pressured to display portraits of Xi Jinping and sing the Communist Party anthem at the start of the services. The level of repression was upped a notch when surveillance cameras were introduced to monitor worshippers. As a result, the agreement signed by the Holy See with the regime in Beijing was problematic on many counts. Rogers argued that the desire to address the situation of ‘underground Catholics’ is not wrong, nor does he doubt Francis’ love for China and its people. Nonetheless, the deal itself remains problematic on many counts. Rogers outlines four problems with this deal: its secrecy, substance, timing, and impact.

We only have a piecemeal knowledge of what the deal contains. For example, the Chinese Communist Party regime and the Holy See have agreed on the nomination of Bishops. While the Pope has the final say, Rogers rightly asks whether, “given the reluctance of Rome recently to stand up to Beijing, is it likely that he would actually veto a nominee?” Indeed, the signs that this is likely to happen are already there; at least seven regime-appointed excommunicated bishops are now in communion with Rome, while at least two loyal underground bishops have been side-lined in favour of regime appointees.

Adding insult to injury, this deal comes at a time when Xi Jinping has been cracking down on different aspects of society. Religious freedom has been at its lowest ebb since the Cultural Revolution. In other parts of the country, Beijing’s crackdown strikes at the heart of the protection of human dignity, which the Church seeks to safeguard.

This increased repression is not solely confined to religious freedom. For example, Reporters Without Borders ranks Tibet 176th out of 180 countries in the press freedom Index. There are more foreign journalists in North Korea than in Tibet. The Communist Party governs every aspect of life in Tibet, and any act which threatens its stranglehold becomes a criminal offence. In East Turkistan (or Xinjiang), between one and three million Uyghurs are in “extra-legal internment camps” for ‘re-education.’ The treatment of the Uyghurs is shameful on many levels. For example, the setting up of the Lop Nor Nuclear Test Base led to a situation where the incidence of cancer in the Xinjiang region is higher than in any other part of China.

Hong Kong is next in line for Beijing’s repressive methods. The initial hopes of the Umbrella Revolution were soon dashed as the COVID-19 restrictions provided authorities with a pretext to halt the spread of the pandemic and silence dissent. The national security law is the legal instrument through which further repression can be meted. It proposes four crimes: secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion “with foreign political foes.” The law will effectively decimate civil society, opposition groups, and the independent media. It will be the death knell of freedom of expression and academic freedom. Rogers cites some of the initial effects of this legislation: the disbanding of over 50 civil society groups and the arrest of more than 150 people.

The Chinese Communist Party is also engaging in an aggressive policy in its immediate neighbourhood. For example, it is in Beijing’s interest to ensure that the relationship between Pyongyang and the rest of the world remains tense. China would not like a free North Korea or a unified Korea. Beijing stands to gain from a diplomatically isolated and neglected North Korea.

Worse still, Taiwan is “subjected to an intense campaign of economic coercion and diplomatic isolation from Beijing” involving retaliation against multinational organisations and sports stars who show some sympathy for Taiwan and a wholesale blocking of Taiwan’s participation in multilateral organisations. Rogers contends that Taiwan is a lynchpin of Xi Jinping’s ambitions: “If Mao founded the People’s Republic of China and Deng opened up its economy, Xi may wish the reunification of Taiwan with the Mainland to be his legacy.”

When asked to choose between Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China, many nations choose the convenient and utilitarian choice. Rogers calls out this behaviour:

This is how ridiculous it is today: that a regime that opens fire on peaceful demonstrators, that has no democracy, represses freedom of assembly, expression, information, is the regime that is recognised as legitimate; while a free, vivid, and exemplary democracy, with free elections, free flow of information, freedom of assembly, and where the military is under a civilian-elected government and neutral from the political process, is the one the world calls illegitimate.

This open kowtowing to China is problematic. Rogers cannot be more emphatic in his analysis: when democracies show weakness, a revanchist, expansionist, and ambitious dictatorship such as that of President Xi Jinping sees opportunities. His warning is clear, and the choice is stark: “Either the world is going to stand up to China and change how it is operating, or China’s way of operating now will become the global system.” The prospect of a global system in the image and likeness of Beijing can already be detected; to appease China any further can only be described as sheer madness.