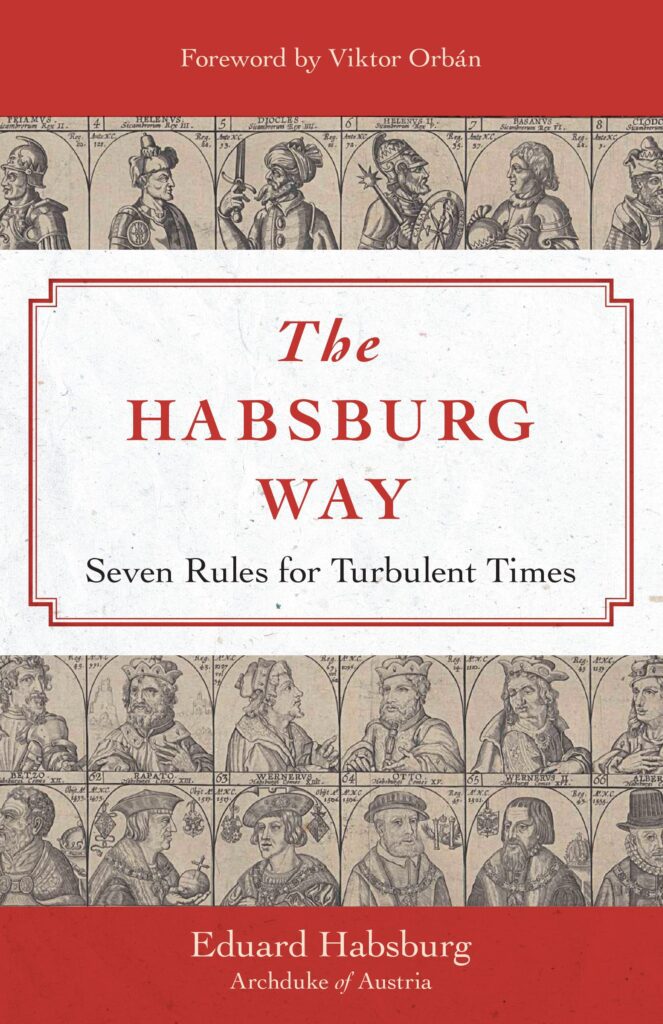

What does a family of “rulers from centuries ago, a dusty imperial family that has long since disappeared” have to offer a modern, progressive, and liberal society? Diplomat, author, and Archduke of Austria Eduard Habsburg-Lothringen answers this question in his new book: The Habsburg Way: Seven Rules for Turbulent Times published by Sophia Institute Press.

Nuggets from general history, together with gems and trivia from his own family’s history, spice up the reading and illustrate the seven rules for our unstable, violent age. In a skilful rendering of history, story, and example, Habsburg identifies the most essential aspects of his family’s diplomacy and convictions that apply not just to princes and the powerful, but to every member of society.

Setting the scene with a succinct tour-de-force of the Habsburg family history featuring illustrious friends and foes—including Emperor Rudolf, Frederick III, Charles V, Philip II, Maria Theresa, Leopold, Franz Joseph, Bl. Emperor Karl, and their adversaries, such as the Ottoman Empire, Napoleon, and the burden of childlessness—the distillation of his family’s philosophy is presented in the form of seven rules to abide by: Get married and have lots of children; be Catholic; believe in the empire; stand for law and justice; know who you are; be brave in battle; and die well. Let’s take a closer look at each one.

Without families, society tends to collapse into isolation and self-centeredness. Children learn from one another and their elders. Eduard recalls one of the most famous sayings about the Habsburgs: Bella gerant alii, tu felix Austria nube (“Others may lead wars, you, happy Austria, get married.”) Habsburg-Lothringen attributes much of the family’s success to “marriage politics,” which proved more successful and less resource consuming than costly wars. He also dispels the argument that the Habsburgs married “their cousins” to retain “pure blood.” It was rather their attempt to keep the Habsburg Empire together, with marriage being the safeguard—sometimes taking significant gambles to make this happen. And the strategy worked. Not only was the unity of the empire a success but of the seventy-three marriages between the Austro-Spanish lines, all of the marriages could be described as happy. Habsburg-Lothringen sums up his thoughts on the matter:

Which is only to say, a successful marriage doesn’t depend on marrying a cousin, but it does require being with someone who shares your values, ideas, faith, and outlook. I will add this additional thought: Because the Catholic faith provides such a deep spiritual foundation, it facilitates the formation of the deepest bond between spouses. Precisely because the Catholic faith is stable, it creates stability in marriages.

That said, not all marriages over the long history of the Habsburg family worked out as smoothly as others, and the author concedes that some were “a catastrophe and a silent martyrdom.” Lastly, he remarks that common faith and values form the best foundation for a happy marriage; they never grow, unlike the excitement of early romance, which “while wonderful, is perhaps slightly overrated in our times.”

Habsburg-Lothringen says that the chapters about faith are written from the heart, and he takes pride that the “Habsburgs were and, for the most part, still are Catholic. Period. Full stop.” The history and identity of the Habsburgs are tightly knit with the Roman Catholic faith from the very earliest beginnings of the lineage. The Catholic faith was something that formed identity and guided the lives of the rulers. Citing a plethora of historic examples, Habsburg-Lothringen explains that the faith was able to fend off major ideological onslaughts such as the Reformation, the Enlightenment, and other smaller revolts against the sacraments. Due to “original sin,” man needs visibility in the life of the faith, such as “processions, rosaries, novenas, devotion to the Sacred Heart, and other forms of so-called popular piety.” Eduard also presents instances when modernization based on the Enlightenment and a more scientific mindset were implemented, for example by Archduke Joseph, who turned “Budapest into an economic powerhouse.”

“After eight hundred years of the intimate Habsburg presence in European politics, members of our family are still putting their faith first and making it the center of their lives. Even if many Habsburg rulers were imperfect Catholics, Christ came to save sinners. And that is a very hopeful thought.”

Aware of the potentially misleading analogy, Eduard compares the Habsburg Empire to the empire in Frank Herbert’s Dune, rather than the Empire in Star Wars. Herbert’s emperor does not have absolute power and can only keep the empire (i.e., the ruling houses) together by diplomacy. While the idea of empire has an acrimonious ring in modern ‘enlightened’ ears, Eduard stresses the significance of “subsidiarity” for the Holy Roman Empire, and the Austro-Hungarian monarchy (as well as a key principle for the United States). It is the idea that “issues should be addressed by the lowest institutional level that is competent to resolve them, whether in countries, states, or other social institutions.”

Poignantly he argues, as an example, that cities should never take responsibility away from families. “Subsidiarity has been a bedrock principle of Catholic social teaching for millennia.” Then he enumerates the reasons why a centralization of power and policymaking is prone to corruption and destruction of society: First, it is inefficient. Second, there is little or no accountability—nobody seems responsible for bad decisions. And lastly, human beings are naturally inclined toward local interaction in families, towns, and countries with common cultures. “That’s just the way we are made,” he adds.

Whenever higher levels of organization, removed from the issues they are confronting, impose suffocating measures in the name of an idea, an ideology, or the latest scientific fad, the tentacles of a new Enlightened Absolutism (‘we know more than my subjects; we know what’s good for them; and we will enforce it’) are beginning to spread. And your response should be clear …: protest … and demand that the principle of subsidiarity be respected.

The core value, Eduard Habsburg asserts, of nobility is the responsibility to serve, which in turn means to put one’s own interests second. In the modern age, where many monarchs have very limited constitutional power, their real power is the “power of example.” This stands in stark contrast to the present political climate, in which politicians are more naturally tempted to use their careers as paths to personal advancement and profit.

Respect for the law is an essential responsibility of the active monarch. A poignant example is Charles V, who looked at the people of the New World not as servants to be exploited, but as subjects to be treated fairly. He once wrote that the indigenous people “are our responsibility, for the honor of God and the sake of justice.”

Habsburg also recounts the meeting of Franz Joseph and Theodore Roosevelt in the Hofburg in Vienna. When the former president and Noble Peace Prize winner asked the emperor to explain what exactly he was doing, the emperor answered simply: “The idea of my office is to protect my people from their politicians.”

Otto of Habsburg often repeated the phrase: “Those who don’t know where they come from do not know where they are heading because they don’t know where they stand.” He also indicated that the Habsburgs stood for continuity and that traditional values were a matter of honor. Eduard points out: “Knowing who you are gives your sovereignty over yourself. It will give you confidence not to be swayed by fleeting fads but to follow the truth about yourself and about God.”

While historically the Habsburgs relied on diplomacy in formulating their policies, they did not shy away from battle when it was inevitable, for “human conflict is as old as Cain and Abel, and wars are as old as mankind.” The most notable battle could be considered the Battle of Vienna on July 14th, 1683. Fifteen thousand soldiers on the side of the West fought against 150,000 Ottomans. The siege lasted two months, and Vienna was engulfed by enemies. But when the Polish king Jan Sobieski crossed the Danube and teamed up with reinforcements from Saxony, Bavaria, and other countries, the dynamics of the war changed. After attending Holy Mass, he led 18,000 horsemen—the greatest cavalry charge in history—crushing the Ottoman lines and attaining victory.

In a life full of uncertainty, one thing is certain: death. While death is certain, heaven is not. Eduard reminds the reader that “most people seem blissfully unaware that there is a possibility that they may end up in Hell for all eternity.” He goes on to explain that even in death, the Habsburgs were aware that they had to “serve” by giving Catholics a good example of how to die. Living well channels into dying well, and the wish to die well leads to living well.

Concluding, Eduard Habsburg-Lothringen looks to the future of the “Habsburg way of life.” Otto von Habsburg, the head of the house, who died in 2011, paved the way for a future vision of Europe. Since the birth of the Paneuropa Union in 1952, he was a tireless defender of the project of Europe as a unified whole but with subsidiary parts. According to Eduard Habsburg, this is a project worth fighting for.

Regarding the current political landscape, Eduard says Hungary “serves as a beacon of hope in today’s chaotic world:”

Hungary, like Poland, is blessed to have political leaders who live their faith visibly. Indeed, Christian faith has a very active presence in our public square. Hungary embraces policies that encourage families to have more children. Hungary strongly believes in subsidiarity with respect to international bodies. And most importantly, Hungary takes law and justice very seriously. If there is any country in Europe that ‘knows who they are,’ it is Hungary. It is not for nothing that it has two Habsburg Ambassadors in its services.” As a closing appeal, Eduard writes: “The Habsburg family has shown how to implement these values over many centuries and in many very different situations. So ask for these values from your politicians. Demand them. And the next time a politician does something outlandish, ask yourself: What would a Habsburg do now?