84-year-old Lance Morrow is a national treasure, and America has only so many more years left of him alive to wise up and begin reading him as such. Not that his accolades, mind you, could be any more august. In 1981, for essays contributed to Time, Morrow earned the National Magazine Award, once a print-only distinction that has since been profaned into social media and podcasting. Ten years later, he became the first awardee to be nominated a second time. For Henry Luce’s iconic magazine, he wrote more ‘Man of the Year’ features (another journalistic rite since re-dubbed ‘Person of the Year’) than anyone in its hundred-year history.

Morrow had one of Time’s longest careers, joining two years after Luce’s death in 1967 after a brief stint in local news, and retiring in the late 2000s to live with his wife, an author and poet, in an upstate New York farm. Whilst at Time, he notably covered the 1967 Detroit riots, the Vietnam War, the Nixon administration, Watergate, and other such topics. At present, he contributes even more widely to the Wall Street Journal and City Journal, with peerless topical width and stylistic flair. To add distinction to prestige, his byline boasts a fellowship at Ryan Anderson’s D.C.-based Ethics and Public Policy Center (EPPC). Younger journalists call this a ‘sweet gig.’

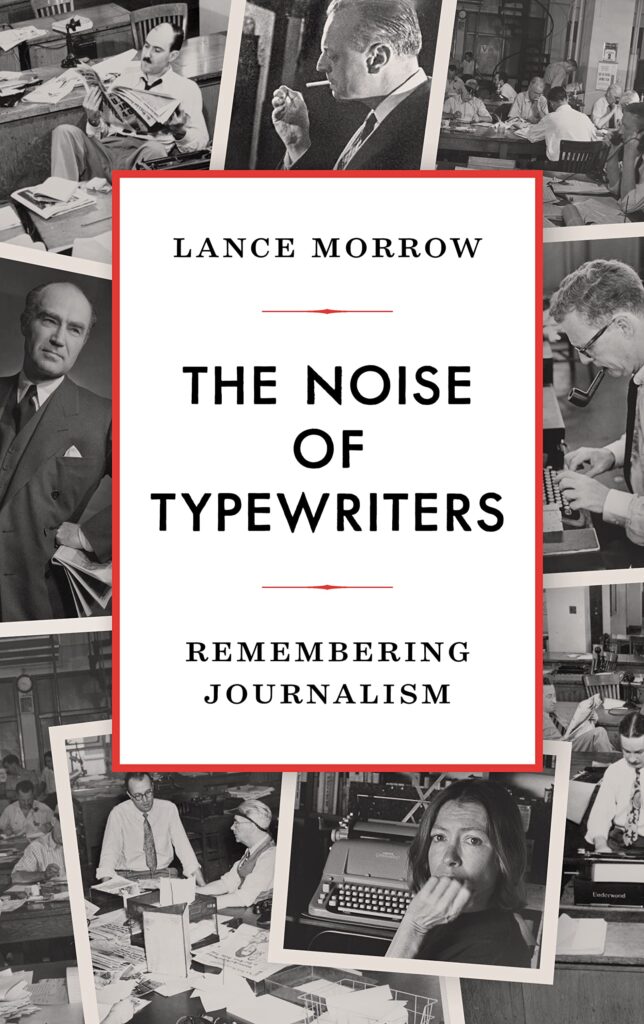

But Morrow’s milestones are hardly the reason Americans concerned with journalism’s future should chase his byline before his light dies out. A son of privilege after all, he grew up a Beltway creature with two journalist parents—his father dabbled as an aide to Nelson Rockefeller—saw power up close himself working summers as a Senate page, and graduated with honors from Harvard. He seemed destined for no less distinguished a career, given his elegiac sensibility and his bewilderingly gifted prose. The reason why Morrow matters is that he may well be the last living bridge to a bygone age in journalism—an age holding lessons for an industry facing near-extinction from the challenges of social media and new business models. Morrow revisits these lessons in The Noise of Typewriters (2023), a memoir of his 40 years at Time, which turned 100 in March. The book reads like a spate of nostalgic ruminations amounting to “an intensely personal study of an age that has all but vanished.” A canvas of the 20th century, it portrays the “statesmen and dictators, saints and heroes, liars and monsters and the reporters, editors and publishers who interpreted their deeds.” Among them stands out Henry Luce, the century’s “most consequential journalist” per Morrow.

The son of Presbyterian missionaries, Luce grew up in China. He moved stateside at age 15 as “an immigrant with all the advantages of the old stock,” in Morrow’s words, “but with the fresh eye of a kind of greenhorn.” He carried what Morrow calls “a fantasy of some sort of Christianized China” that led him to feature Chiang Kai-Shek and his wife 11 times on Time’s cover. He was stellar in high school and at Yale, where he stayed through World War I as an undrafted reservist. In 1917, he was among only four freshmen hired by the Yale Daily News, though he later lost his bid for chair to his friend Britton Hadden, one among four classmates with whom he quit his job to found Time in 1922, at the age of 23. Until 1964, Luce remained editor-in-chief of Time and its sister publications: the general interest Life, the economic and business-focused Fortune, and Sports Illustrated. He died in 1967 worth about $100 million in Time Inc. stock and donated it all to the namesake foundation his son set up. Morrow calls Luce “the key to understanding journalism in the 20th century” and the “Henry Ford of magazines,” while he called Time a “superpower of print.” Previously, historian Robert Herzstein had referred to Luce as “the most influential private citizen in the America of his day.”

Luce is widely credited for transforming journalism and America’s reading habits, but Morrow’s version of how he pulled this off differs from the mainstream account. He cites Robert Hutchins, who claimed Luce had a deeper impact on the American mind than the country’s entire system of public education. Yet Morrow elides the significance of Timestyle, the revolutionary style Hadden pioneered, and Time’s trend-setting emphasis on brevity (its original name was Facts and it was meant to be read in an hour). Instead, Morrow emphasizes the broader vision these practices served. “Luce’s great contribution,” he writes, “was the idea that everything in life could be observed, reported upon, understood. The news could be sorted out, coped with, grasped, and interpreted for the American middle class that would, if all went well, inherit the earth.” Luce’s strategy amounted to journalistic populism, though only insofar as he targeted a vast readership, for he worked—and inspired others to work—as “a model of the first-class journalist.” His vision of the profession—“journalism is witness, the journalist is the eye”—relied on the “sanctity of facts”: “as a fact-gatherer,” Morrow writes, “Luce proceeded with the ferocious, candid naivete that makes a good reporter.”

Nevertheless, this fact-worship would, on its own, be the equivalent of hammering a soccer player with the importance of scoring goals, or a politician with the necessity of winning elections. “Good journalism,” writes Morrow, “is to be judged by the truth it discloses, but there are many ways of getting at the truth and expressing it.” Much like Herodotus, the ancient father of journalism, Luce believed in the importance of memory on par with history, in facts on par with their meaning, in conveying how events are experienced at the time of writing on par with the events themselves. This leeway for interpretation—this window of subjectivity—is the niche in which Luce thrived, the distinction that set him apart from the diligent though mechanical reporters that staffed his rival publications, and what turned him into “a preeminent American mythmaker of the 20th century,” in Morrow’s words. “Luce’s journalism sought to present a living record of men and women in the act of making history,” Morrow wrote, but what constitutes history is down to the individual journalist’s discernment. “Henry Luce, by some alchemy … to do with exaggeration and the artful selection of details, used his publication to proliferate legends. Legends endure. Legends are memorable.”

Morrow is most interested in what drove Luce to impress his mythmaking upon Time’s journalism: “He would use his magazines to invent, or reinvent, America according to his moral and religious design.” That design had plenty to do with his “idea of America as a great thing in the world—a doer, a God-sponsored winner, a force.” In February 1941, nine months before Pearl Harbor, Luce famously penned “The American Century,” a piece that would have likely been passed over by specialist journals for its lack of anchorage in geopolitical realities, but which came closer, mysteriously, to capturing those realities than any front-page Foreign Affairs essay. Such was the power of Luce’s journalism. His essay urged the U.S. to forsake isolationism in favor of a missionary’s global role, by entering the war in defense of democratic values. Teeming with religious references, the essay summoned American ideals to “do their mysterious work lifting the life of mankind from the level of the beasts to what the Psalmist called a little lower than the angels.” Morrow relates Luce’s idealism to that of 19th-century historian George Bancroft, whose “idealized vision of America was also not hypocrisy but something else—a kind of yearning, an Emersonian idealism.”

Luce’s devoutness seldom matched his temperament. “For a follower of Christ,” writes Morrow, “his heart was somewhat cold.” Tender and courteous while off-duty but uncouth to the point of rudeness with his staff, Luce was “a beast of the prime.” As a result, Morrow confides that he had “a hard time” making up his mind about him. He recounts the banishment Luce underwent when the last editors he appointed were replaced with a younger crop of boomers, mostly due to his unwavering support of the Vietnam War. “After his death, there came to be a distinct distaste of the founder—an ideological disapproval, a sort of embarrassment.” The souring on Luce suggests that, in the grand scheme of history, the increasingly regular animosity between the low-level, woke-inspired staff at popular magazines and the editors who at times refuse to unpublish right-wing voices under pressure is perhaps nothing new. Morrow, for his part, broadly remains an admirer of Luce. After successive evolutions in Time’s management since Luce’s death in 1967, Meredith Corporation sold the magazine in 2018 to Marc Benioff for $190 million. At the time, Morrow penned a moving eulogy that began with a lapidary hook: “Henry Luce’s America died about the same time that Luce did.”

Where does the difference between Luce’s America and what came after lie? Morrow writes that “the new people … brought an impatient depthlessness to their work. They lacked resonance.” For one thing, the rulebook of successful journalism has been turned upside down. “In the 20th century,” writes Morrow, “it proceeded on the assumption that there was such a thing as objective reality,” whilst “in the 21st, journalism has plunged into the metaverse.” The markers of journalistic success, furthermore, have changed entirely: grit and resilience in the former, shock value and virality in the latter. “The America of the 20th century is easier to grasp than that of the 21st century, when machines grow more precise in their grasp of the universe and human brains become more and more confused—more parochial, more hysterical.” But even more crucially, Morrow suggests journalism is losing something more momentous: its capacity, whilst describing events, to shape them. Whilst in the 20th century it “touched history almost continuously, and sometimes altered it, changing its course from what it might otherwise have been,” in the 21st century it seems reduced to the role of a passive bystander. Journalists longing for some history-shaping action have in Morrow—and in Luce—a role model.