If you’re like me, you spend more time than you should in second-hand bookstores. You’ll wander into them—whether to procrastinate on work or spend an afternoon with a friend—not looking for a particular book, but merely with a roving eye, interested to see what chance cover will step into view. When you’ve put yourself in certain sections long enough, you begin to make acquaintances: some whom you avoid as soon as you notice them, and others who tempt you. Despite the usual excuses (a lack of spending money, a guilty conscience about the full and unread bookshelf at home, a busy social life that distracts from reading) you might conjure up, eventually they end up coming home with you, for an uncertain fate, of being read sooner or later or never at all.

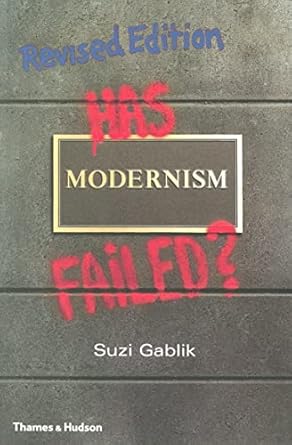

One of the more recent iterations of this familiar series of events brought me face-to-face with the recently deceased art critic Suzi Gablik’s Has Modernism Failed?—an entrancing series of essays, published 40 years ago, examining the contemporary art scene as it then existed. Despite an updated version of the work being released 20 years later in 2004, the original is well worth the read, criticizing not only individual works of art (if one may in fidelity to the truth call them that) but also the conditions—aesthetic, economic, and spiritual—which led the world of professional art down such a disastrous blind alley.

About ten years ago, I recall being on a family trip to France and spending several days in Paris. We were staying north of the Seine, near the Rambuteau metro stop, and frequently walked past the Centre Pompidou, which Google Maps describes as an “architecturally avant-garde complex” that contains the National Museum of Modern Art. For those who haven’t had the misfortune of seeing it, it looks like a cross between a parking garage, a hamster cage, and a minimalist high-rise that, for some reason, someone deemed fitting for human habitation. My mother and her cousin were curious enough to stop in one day, but I don’t believe they lasted 20 minutes before deciding not to waste any more of their time. After all, in Paris, one can see Manet, Monet, a stunning statue of the Madonna and her crucified child at Notre Dame. Why make time for modernism’s various eyesores?

Gablik’s project in this book is fascinating because she tries to bridge the gap between people within the art world and those, like myself, who are outsiders. However, she does so from within the paradigm formed by modernist sensibility, even as she vigorously grapples with its presuppositions. She surveys “the fate of art” in relation to what she dubs the “great modernizing ideologies”—namely, “secularism, individualism, bureaucracy, and pluralism”—but her book is not primarily theoretical. She recurrently turns to individual 20th-century artists and their works to expand upon and elucidate her arguments.

Her cast of characters includes names well-known to those with a little knowledge of recent art history—Andy Warhol, Marcel Duchamp, Kandinsky—as well as lesser-known ‘performance artists’ like Chris Burden, (who “had himself nailed to the roof of a car” in “a work called Transfixed (1974)” and in 1971 “had himself shot in the left arm by a friend holding a .22-caliber rifle” because, as he said, “It’s something to experience … It seems interesting enough to be worth doing it,” and Mike Parr, who cut off his own prosthetic arm with an ax.

On a popular level today, the quest for artistic experience is similarly charged with violence, leaving numerous children and others dead due to TikTok challenges or seeking the perfect selfie. In her first chapter, examining the debate between the ‘art for art’s sake’ modernists and the socially engagé avant-gardists, Gablik sides with the neo-Marxist critic Peter Fuller, writing, “If art can be anything the artist says it is—it will also never be anything more than that. The real crisis of modernism, as many people have rightly claimed, is a pervasive spiritual crisis of Western civilization: the absence of a system of beliefs that justifies allegiance to any entity beyond the self.”

“We need not be Marxists,” Gablik insists, to recognize “the dark underbelly of individual freedom in our society,” a statement more true in the 2020s than when she originally wrote in the 1980s. Liberty has indeed generally degenerated into license, even among ostensibly right-wing populations (consider the failure of pro-life ballot measures in red states in the U.S. and the Republican Party’s recent tactical retreat on abortion and so-called gay marriage). Gablik does not rest content with blaming contemporary artists for sponsoring this kind of egoistic relativism but turns to examine how “anxious objects,” as Harold Rosenberg termed them, functioned to challenge the forces of capitalism and faceless bureaucracy, whether through their subversion of artistic norms, such as Duchamp’s infamous urinal, or through the more benign refusal of artists such as Robert Janz or John Davis to treat their artworks like commodities for sale. They would rather make works free for public consumption (Janz specialized in large chalk drawings on public streets) or as gifts for others (as Davis treated his “fragile, devotional objects” that “resembled aboriginal ceremonial sticks or shamanistic prayer arrows”). Gablik’s citation of Lewis Hyde on the importance of the artwork being a gift rather than one market product among many should provoke us to think again about the relationship of art and money. But such a claim sits uneasily with the propagandistic oikophobia of Duchamp, whose best critic remains Sir Roger Scruton in his BBC film Why Beauty Matters (2009).

Calling Scruton to mind points to a general deficiency in Gablik’s analysis: a lack of attention to the role that the rejection of beauty played in visual modernism’s demise. In neither the abstract expressionists, who valued personal expression, nor the avant-gardists, who valued political speech acts through painting or sculpture, was beauty, a transcendent splendor that radiates visibly for both the hoi polloi and the trained artist, considered the north star of the artist’s vocation. It is unfortunate that alongside her consideration of visual modernism, Gablik did not consider the tradition of literary modernism, particularly as on display in the journey of Stephen Dedalus in James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916). This is especially the case given the novel’s reliance on Thomas Aquinas’ definition of beauty and Aristotle’s understanding of analogy, as argued by Fran O’Rourke and helpfully summarized here by Joshua Hren—which would have assisted her in seeing a third term between the binary oppositions that scaffold her work: of individualism and collectivism, tradition and modernism. It would have underscored the connection between beauty and justice seen by philosophers from Aristotle, who spoke frequently of the beautiful (to kalon) and the just (to dikaion) together, to Elaine Scarry, who has elegantly argued for the capacity of beautiful things to aid us in becoming just.

For beauty is not an individual possession or a statist pomposity, but a common good. And common goods, unlike the utilitarian concept of the greater good, are also irreducibly personal, belonging to human persons who exist within what Alasdair MacIntyre has called “traditions of moral inquiry.” In her final chapter, Gablik grapples with the implications of MacIntyre’s After Virtue (1981), published just three years before her own book; but unfortunately, she seems to conclude that, as desirable as tradition may be, a world characterized by clearly defined social roles and a common faith cannot return again. In her chapter on secularism, she strangely insists that her desire for a return of a shared sacred does not require traditional religion, even as such religion seems today the necessary condition for the transgressive sacrilege-as-art that was the now infamous “Last Supper” tableau at the Summer Olympics.

This wistful insistence on the fundamental triumph of modernism over tradition leads Gablik to hope for a new image of the artist, which unfortunately is simply a new figuration of what Joyce showed us in Portrait: Dedalus’s desire to “fly by those nets” which he claims hold back the soul, namely “nationality, language, religion,” to become a new priest, a new Vulcan rather, “to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.” She confesses to a longing for the return of “the artist in his role as shaman,” who “becomes a conductor of forces which go far beyond those of his own person and is able to bring art back in touch with its sacred sources; through his own personal self-transformation, he develops not only new forms of art, but new forms of living.”

Such high-flying romanticism rings considerably hollow, after one reads Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) and sees the shallow wreckage of Dedalus’s life. It is but a secularized version of the potential ‘return to cultic paganism’ which Michael O’Brien, Susannah Black Roberts, and R.J. Snell, among others, have justly criticized. One wishes Gablik had read T.S. Eliot’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent” to see her binary of tradition and modernism deconstructed. While contemporary artists of visual modernism may wish to repudiate tradition, as long as there is a viewing public that can witness beauty, loving it at the Louvre and worshiping Him in the tabernacle at the Lady Chapel, there will be a desire for tradition. To understand that desire, we will need another, albeit very different, Evelyn Waugh, who, as Fr. Ian Ker once put it, saw the artist, like the priest, as a humble craftsman, working within certain rubrics that allow us continued access to the Beauty whom St. Augustine described as “ever ancient, ever new.”