“Africa begins at the Pyrenees” is an old French jibe at Spain, a comment engendered by bitter memories of savage Spanish resistance to the Napoleonic invasion, of little wars (‘guerrillas’) led by illiterate peasants and fanatic local priests against the French occupation. It was part of a larger idea that Spain was different; it was wilder, more fanatical, somehow elemental, strange, and degenerate with more than a touch of the Moor and the Jew. It was part and parcel of the larger narrative that also includes the notorious Black Legend, that 16th century, enduring tale of Spanish Catholic perfidy assiduously disseminated by Dutch and German Protestants, Enlightenment French philosophes, and Anglo-Saxon imperialists.

Spain was different, and that difference was in ways both shocking and distasteful but sometimes also attractive and fascinating. So it was for the many English, French, and Americans who have written, often with great skill, passion, and insight about Spain in the 19th and 20th centuries. Washington Irving and Hemingway, Dumas, Mérimée, de Montherlant, and Maurice Barrès, George Borrow and Richard Ford. One lesser-known name in that great tradition, at least to English-speaking audiences, is the French writer Jean Cau (1925-1993) who wrote extensively about Spain, especially about bullfighting, for more than 20 years.

Cau the man is almost as interesting a subject as the traditional Iberian culture that he documented so extensively. Cau was a scion of the French South, of le Midi, born of peasant stock in a region known for its medieval heresy, the Manichean Catharism so zealously stamped out by the brilliant and ruthless Simon de Montfort during the Albigensian Crusade in the 13th century. A bright and ambitious boy, Cau was weaned on a working-class French communism common in those days (his aunt was a member of the Resistance during the Second World War and a prominent communist politician).

Hungry to succeed in the Parisian cultural firmament, in 1947 he was able to wangle a position as secretary to the already celebrated existentialist and Marxist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, a position he held for nine years. He began to work as a journalist and opinion writer and slowly moved towards the political right, his very own idiosyncratic type of right-wing thought. In 1961, he won the Prix Goncourt, France’s most prestigious literary award, for his novel The Mercy of God (as far as I know, the only one of his voluminous works to have been translated into English). Cau’s first books related to Spain (although The Mercy of God was written in Spain) appeared at the same time as he became part of the entourage of matador Jaime Ostos during the 1960 season, traveling with them by car to different bullrings across Spain. By 1965, Jean Cau openly supported de Gaulle against the socialist Mitterand, and his shift even further to the right was solidified by the brutality of the Soviet Union and the French student revolt of 1968. As his old mentor Sartre flirted with Maoism, Cau memorably described May 1968 as “that strange revolution which sees the sons of the bourgeois throw cobblestones at the sons of proletarians.” Proud that his “ancestors had been peasants since the dawn of time,” Cau saw through the popular progressive cant of the day. Asked if maybe those students saying “make love not war” might be right, he answered, “no, make war! Wage war on your cowardice, your laziness, your lack of culture and pretensions!”

Anti-feminist, anti-American (from the right), sarcastically mocking the liberal Christianity of the day and wielding a prolific and vicious pen, he was nothing if not provocative. He would describe Euro Disney as a “cultural Chernobyl” that would “irradiate millions of children.” He saw both communism and American-style “globalist democratism” as existential threats to European culture, indeed to any local culture. In fact, the American threat was even deadlier because it was clearly the more powerful one, a cultural menace that would lead to a globalist system of government erasing all national cultures and local distinctiveness. At the same time, the New Right provocateur Cau would write a paean to, of all people, the Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara, a decade after his death, seeking to remake the Marxist butcher as a man of action, an adventurer who fought for his ideals. Jean Cau saw himself as a literary adventurer, an outlier, both literary and political, and from the small parts of his extensive work that I have been able to read, he reminds me somewhat of Spain’s Guillermo Gimenez Caballero (1899-1988), also originally a leftist who moved right; both talented, forgotten writers, extreme and eccentric, who delighted in literary bomb throwing.

Cau saw Europe’s decadence as having a spiritual origin: The globalist, statist, levelling, emasculating, and decayed spirit of the age that he saw as increasingly dominant had Christian roots in antipathy to the manly and archaic virtues that he prized and found in, for example, old Spain and in bullfighting. The French Revolution, Marxism, ‘human rights,’ and democracy were all Christian offshoots that had produced toxic fruit. He toyed with the sun-worshipping paganism of the European far right, but when he died of cancer in 1993, his funeral service was held in Carcassonne’s Saint-Michel Cathedral. He is buried in a Catholic cemetery, a cross on his tombstone. As a Christian, I reject Cau’s blame game of “playing with paganism to needle the Christ worshippers” narrative, but his bitter sarcasm towards the Christian faith has some real echoes today in the trenchant criticism of those who see the identity politics of le wokisme as a type of leftist Calvinism, a stern and pitiless religion of original sin without divine salvation or supernatural absolution. That is something worthy of Cau’s mockery.

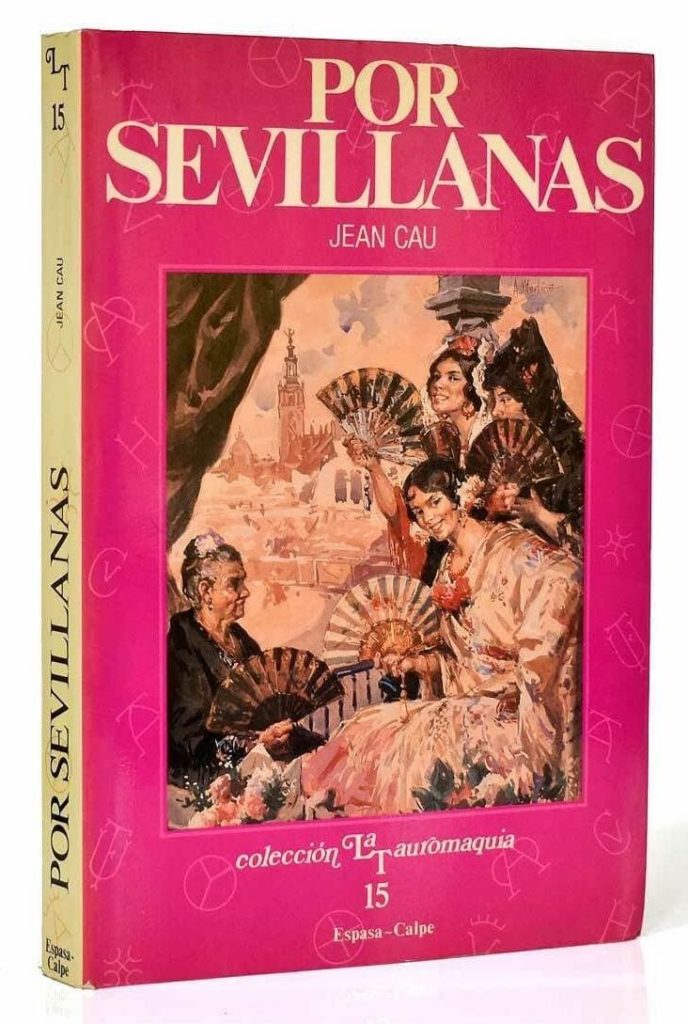

Happily, in Spain, Jean Cau, the pagan Cathar, almost becomes Catholic. Cau’s great work is Sévillanes (1987, published in Spanish in 1988 as Por Sevillanas). Ostensibly about bullfighting and published in Spain as part of the Colección La Tauromaquia series of books, it is actually the greatest book published by a foreigner about the city of Seville and one of the great books on Spain. It can be regarded, perhaps, as Seville and Andalusia seen through the eyes of an extremely knowledgeable, fluent Spanish-speaking Frenchman, a deep aficionado of bullfighting, and so much more, and the product of decades on the ground in the city and its countryside, “a work full of emotion and hope” as one Spanish writer described it. Cau himself described Spain as “the motherland of my passions,” in contrast to France, “the motherland of my ideas.” Neither a history nor a guidebook, his Seville book is “chronicle, story-telling, memories and reflections.” Written in the last decade of his life, it is “perhaps because of Death, all deaths, including my own, that I have come to talk with Spain, trying to recover my steps, but what pain, twenty years later, to search for what has been erased.”

“All of Andalusia is perfumed with the sacred,” but at its heart is “the Andalusian bride which bears the loveliest name—to me—in the world: Seville.” The city, with her Giralda tower, her Virgins and Christs, her illustrious Real Maestranza bullring, and in the heart of the city, “like a white carnation, the barrio of Santa Cruz.”

Cau’s beautiful descriptions of the city, with its traditions both homely and grand, are indeed tinged with melancholy. He remembers first crossing the border decades earlier, “Spain no longer stinks – deliciously – of olive oil, like the perfume of a woman.” He worries about the pessimists, like himself, who fear that in Spain there will one day be no bulls and no fighters of bulls, like America with its millions of cattle and not one toro bravo. But the book is not a sad one; rather it is filled with the joy of living, of feast days, and processions of Holy Week with their scent of candles, lilies, and carnations, of bullfighters in their suit of lights, of the dancing and drinking of the great April feria, of the ordinary people of the city, the bootblacks and beggars of the past, the mustachioed waiter Mariano who quizzes Cau on the points of arcane taurine lore from pictures hanging on the walls of his bar, nodding with pleasure at the right answers. Then the aristocrat who points to his wall in his palace, “that is the mounted head of Islera, the mother of Islero who killed Manolete, that other is Nazareno from 1883, who took 15 jabs from the picador’s lance and killed six horses.” Lamenting Seville’s modernization over twenty years, Cau closes his eyes: “let’s see – bulls, saints, Virgins, Christs, dancers …l et’s breathe, not all is lost.” An old friend welcomes him back to Seville, “Is there anything better than Valdepeñas wine? We will drink it at ‘Las Cuartillas’ and we will talk of bulls. Among men, we will be happy.”

The bulls in the book are almost as vivid as the people. There is a striking sequence of the life, fight, death, and afterlife of a brave bull seen from the perspective of the animal. Another digression discusses the caste (casta, or breeding) of the brave bulls: “the world of bulls does not joke about this. Their bloodlines are as illustrious as the Capets, the Habsburgs or the Prophet Muhammad.”

In spite of Cau’s mocking of Christianity in France, his treatment of the faith in Seville is respectful. Holy Week is when the entire city manifests itself in hundreds of thousands. It is not tourism or folklore; it is not for foreigners who cannot—except for Latin Americans, heirs of Hispanidad—truly understand it. The mantles of the Virgins are like the tails of sacred peacocks, adorned with jewels donated by the great matadors and the nobility. He recalls the image of the Virgin of the Stars of the gypsy quarter of Triana, the only sacred image to process in 1932 when Red Seville “was drunk with Republican wine” as the churches and convents had burned in the spring of 1931 with the coming of the Second Republic. He muses that “simply, God exists because he has always existed, particularly in Seville and in Andalusia, where they believe in him, and as the proverb says, they believe even in summer when the sun shines like hell on the land.” The townsmen, who may have lived profane lives during the year, return as penitents during the holy days. The socialist mayor, who declares himself an agnostic, has a son laboring as one of the faithful crew carrying the palanquin of the Christ of the Great Power. On Easter Sunday the streets shine with melted wax so thick that you could skate on them.

Over 30 years since the book’s publication, some of what Cau feared has come about in Spain. Seville is certainly more homogenized and globalized than it was in the decades since the book appeared, certainly more so than during the time of the “genial Caudillo” Francisco Franco (Cau uses the term intentionally to mock the left) when Cau first visited the country. Spain today faces an existential political crisis, as the ruling socialist-communist coalition relies on the votes of extreme nationalists in Catalonia and the Basque region to hold onto power. So, paradoxically, the rulers in Madrid seem in lockstep with whatever globalist drivel is coming out of Davos, Brussels, and the UN, seeking to homogenize the globe, while at the same time they rely on the votes of atavistic, xenophobic ideologues who are anti-Spain in these autonomous regions (they ban Spanish and also hate bullfighting, not so much because of animal rights, but because they see it as a symbol of the despised Castilians). The left has had (with the votes of separatist nationalists) a bare majority since 2020 but embraces a breathtakingly ambitious agenda intended to erase the remnants of old Spain, including the monarchy, the constitution, and the unity of the country. Bulls and churches too, no doubt.

Spain and Andalusia are today in deep economic pain. Two years into the pandemic and two canceled Holy Weeks later, thousands cheered the return of the first street procession of the Christ of the Great Power in October 2021. The green shoots of the Seville of tradition cautiously sprout and look hopefully, if uncertainly, towards springtime, the season of Easter, the bulls, the great fair, and the pilgrimage to El Rocío. Much has been lost but much remains. And even though Cau’s real-life Seville has faded, the spirit of place, the mood, and deep wellsprings of the people, town, animals, traditions, and its countryside are described with such knowing affection and vividness that they endure.