“The Great City of Tenochtitlan” (1945), a mural painted by Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and located in the Palacio Nacional (National Palace)of Mexico, located in El Zócalo in the center of Mexico City.

In a technocratic age awash with information, we sometimes seem to know nothing. In the West in particular, we either misremember, forget, or demonize our own past. Perhaps in no other age has the contrast between material wealth and intellectual poverty been so vast.

All too often we weaponize the past in new ways. In Spain, the left in power seeks to politicize both history and memory in increasingly draconian ways. Across the liberal West, names are changed and historic statues come down, often according to an arcane and hermetic accounting of the past. Psychoanalyst Vamik Volkan memorably wrote about ‘chosen trauma,’ the collective memory a people or ethnic group have of traumatic past events, and yet today not all traumas are equally ‘chosen’ by elites. Some are more valuable than others. To talk about the trauma of enslaved persons shipped to the West is acceptable, but to refer to the trauma of enslaved persons under Islamic regimes risks the dreaded label of Islamophobia. The European conquest of the Americas is regarded as infamous, but the conquest of subject peoples by non-Europeans elsewhere will be explained away or excused. Loaded terms such as imperialism, colonialism, genocide, ethnic cleansing, and minority rights somehow lose their strange power when the potential culprit is not from the West, or not a Christian.

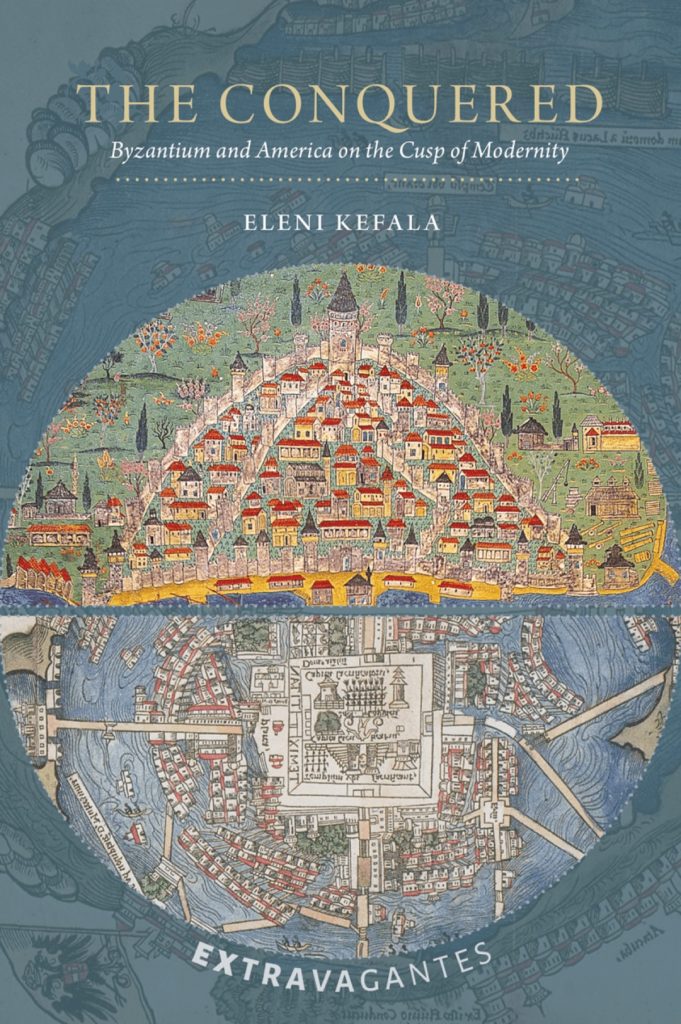

Amidst much forgetting, some remember—and the new book by Eleni Kefala, Senior Lecturer at the University of St. Andrews, is a bracing, short but expansive, study of poetic expressions of the fall of two fabled civilizations. The Conquered: Byzantium and America on the Cusp of Modernity takes a nuanced, richly textured look at three anonymous sorrowful poems, one on the fall of Byzantine Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, and two about the fall of Aztec Tenochtitlan to the Spaniards and their indigenous allies in 1521—two hugely consequential events in human history only 68 years apart. Of course, the Byzantines called themselves Romans (even though they were Greek speakers) and the Aztecs likely did not call themselves Aztecs but Mexica and they spoke the Nahuatl language.

Anaklema tes Konstantinopoles (Lament for Constantinople) was likely written within living memory of the fall of the city by someone well-versed in contemporary historical accounts, perhaps based in Cyprus at the court of Queen Helena Palaiologina, niece of the last Emperor of the Romans. It is her uncle, Constantine XI Palaiologos, who died fighting on the last day of his empire, who is the poem’s tragic hero, “the prudent and strong, and exceedingly brave, the mild-mannered and affable, the pride of the Romaioi.” Constantine courageously fought against a larger and better armed foe (exactly how he perished is not known).

The last emperor lost with such a powerful image of tragic regal heroism that he long ago entered Greek Orthodox national mythology (even though he died a Catholic in union with Rome). The poem that Kefala examines is a lament that follows the model of past laments for the fall of great cities (including the notorious sack of Constantinople in 1204 by ruthless Crusaders) found in Greek literature. This is an elegy for the end of things: the emperor beheaded, the city sacked for three days, Byzantine notables executed, boys and girls enslaved for the harem, the churches looted, and the holy icons trampled underfoot by the impious. The weeping and mourning are as if it were the end of the world, and “Mehmed the dog” (Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II the Conqueror) a forerunner of the Antichrist.

The two Nahuatl pieces, Huexotzincayotl and Tlaxcaltecayotl, are also short epic poems about war and sorrow common in the literary tradition (what survives) of the pre-Columbian Mexica, probably written by members of the noble classes being educated in the schools of 16th century New Spain. These poems are also laments at the fall of a great city and the overthrow of a dynasty, but with some very vivid differences to the example of Constantinople. The fall of the Aztec Empire was more “a massive rebellion of indigenous city states” than a purely Spanish conquest by Hernan Cortes; this is reflected in the poetry which is as focused on warring indigenous people who allied themselves with the Spaniards as the Spaniards themselves.

In a way the Spaniards were themselves another tribe, the Caxilteca (‘people from Castile’) along with the Tlaxcalans and Huexotzinca. In this sense indigenous people also were both conquered and conquerors, indeed some of them would serve as “Indian Conquistadors” themselves in fighting other indigenous people. This is seen in the taking of Guatemala, accomplished by Spanish-led, largely indigenous armies. Cortes’s own force, at the taking of Tenochtitlan in 1521, was reportedly about one percent European, and the indigenous peoples on the winning side were rewarded and kept their privileges in colonial Mexico for generations.

Kefala notes that these two poems are unusual in that they are deviations from a broader pattern: many colonial era Nahuas did not see themselves, unlike the Greeks, as a conquered people. The Spaniards were mostly not concerned with “wholesale Hispanization except in the field of religion” (the first Nahuatl grammar was written in 1547 by a Franciscan priest, three years before the first French grammar was printed). The Mexica were able to fit Spanish rule and the accompanying conflict and epidemic disease into an already existing indigenous discourse of ongoing cycles of war and natural disaster. The fall of the Aztec capital was immediately traumatic but less of a lasting trauma than the fall of Constantinople to the captive Greek nation during the Turkocratia.

But if less shaken at the ending of an empire than the Eastern Romans, the Aztecs still lamented and wept at their fall, with verses recalling beautiful Mexica maidens being carried off to marry the conquerors, the women covering their faces with mud to make themselves less pretty. One of the poems laments seeing the last Aztec Empress (Isabel) Tecuichpotzin, who was probably a young teenager, in the hands of the European conquerors.

The three poems, the Greek and the Nahuatl, show the sting of defeat and dismay still raw and immediate, the Greek perhaps rawer and deeper. Both subject peoples would adapt to the conquest in their own way. Greeks would serve the Ottoman Empire for centuries, some attaining great wealth and power. The surviving Nahua elite would also find their way in a new society, like the Greek elite some of them would be tax farmers in the new imperial order. Little Isabel Tecuichpotzin would be treated with great deference by the Spaniards, eventually marrying and producing offspring, leading to the current day noble Spanish Dukes of Montezuma and hundreds of descendants in both Spain and Mexico.

While the Greeks still lament the fall of Constantinople and the Anaklema is to be found in Greek textbooks, the Aztec monodies are far more obscure and less influential in Mexican society. This may be because the fall of Tenochtitlan was the beginning and not the end of what we know as Mexico, a civilization characterized more by the Mestizo—the mixture of European and Indigenous—than by full-blooded indigenous Mexicans (there are still almost two million native speakers of Nahuatl today in addition to other many indigenous peoples in Mexico). One Mexican President even authorized a controversial sculpture celebrating Cortes, his Nahua paramour Marina (popularly known as ‘Malinche’) and their son Martin—symbolically the first Mestizo. Constantine XI has several heroic statues in contemporary Greece, but no memorial, as far as I know, in the city he defended with his life.

Modern sensibilities have provided this story with interesting twists playing into domestic politics in both Mexico and Turkey. In 2021, at the 500th anniversary of the fall of Tenochtitlan, Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (known as AMLO), himself a pale-skinned descendent of Spanish immigrants, said that he considered it “offensive” to say that the conquest was merited because “among other things, the Mexica ate human flesh.” AMLO demanded apologies both from the King of Spain and from Pope Francis for the Spanish Conquest of Mesoamerica. He didn’t get them. But neither celebrated the 500th anniversary of the conquest.

In Turkey, President Erdogan has tied his increasingly authoritarian rule and that of his Islamist AKP party with symbols of Ottoman greatness, celebrating the conquest in the crudest chauvinistic and xenophobic terms. If you go by the frenzied tone of Turkish propaganda alone, Erdogan wants to recreate the Ottoman Empire, but on a grander, global scale. In 2020, a campaign to turn historic Byzantine churches that had become museums back into mosques reached its peak when the ancient Church of the Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sofia)—the largest church in Christendom for nearly a thousand years—became a mosque again. The move was calculated to play to Erdogan’s Islamist and populist base and was well received nationally and throughout the Muslim world while generating international dismay elsewhere. Under Ataturk the building had become a museum in 1935.

Perhaps even more appropriate for the ahistorical and twisted spirit of our age was the 2012 Turkish film spectacle Fetih 1453, anachronistically showing a fire breathing Constantine XI spitting defiance in a Hippodrome filled with thousands and portrayed with the imperial splendor of Byzantium that no longer existed in the 15th century. The fact that the Romans were heavily outnumbered by the Ottoman forces, the city mostly empty, and the massive ancient walls obsolete, would not have made for good action cinema, at least not from the Turkish side.

While the Americas have mostly embraced the cause of the conquered (even though most inhabitants in the Western Hemisphere have little or no indigenous blood), the Turks and the broader Muslim world embrace the image of the conquerors. In the West, the space between conqueror and conquered seems to have shrunk and even intermingled. There is generally little introspection, if any, in the East for what they destroyed or replaced, let alone sympathy for the fallen adversary. This antipathy often applies to remaining vestigial Christian populations in Turkey which must tread warily. For a Turkish Muslim to be told that he has Greek or Armenian ancestors is often an insult in Turkey. Even though many Turks are of mixed Anatolian origin (Erdogan himself has been derided by some critics as having Pontic Greek ancestors), openly embracing your diverse origin sadly remains mostly a Western fancy.

Kefala’s book is a polished and accessible work of scholarship written during a fellowship at the bucolic confines of Dumbarton Oaks, the research center in Washington, D.C., which happily combines an academic focus on Byzantine and Pre-Columbian Studies as well as garden design and landscape architecture. The result is a delightful text on the role poetic imagination plays in the creation of post-memory of two of the more evocative episodes in early modern history.