Sometimes it seems that our super-wired and connected world has little memory of the past. One of the great tasks of honest people today is that of remembering the calamities and warnings of the past and rescuing the historical record of those who fought bravely against—and often were overwhelmed by—such disasters. One such past and all too present calamity is Communism, a demonic force that the world has not fully shaken despite its record of bloody infamy.

In May 1966, the Chinese Communist Party, already in power for almost twenty years, launched a Cultural Revolution intended to totally purge China of its past—young Red Guards were called upon to fight those in the “Five Black Categories” who comprised the so-called ‘enemies of the Revolution’ (namely landlords, rich peasants, counter-revolutionaries, “bad influencers” and rightists). Months later, in February 1967, Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha (who had been in power for more than twenty years and was Maoist China’s most committed European ally) launched a renewed campaign against religion in Albania, leading to the country constitutionally declaring itself the “world’s first atheist country.”

Like Mao, Hoxha—whose Communism was honed on a royalist government scholarship in France—had persecuted Christians (and Muslims) from almost the beginning of his rule in 1944, when Albania fell into the hands of one of the most savage and rigid of Communist regimes. His government was paranoid and xenophobic, first fervently Stalinist and then slavishly Maoist until the late 1970s. Hoxha, the ‘Supreme Comrade,’ a devotee of vampire novels who enjoyed watching films of the torture and murder of his political prisoners, held onto power until his death in 1985.

Today, we easily forget that Maoist Communism and its various copies—an ideology responsible for the deaths of tens of millions—was quite fashionable in certain quarters in the West in the ‘60s, during the worst years of the Cultural Revolution. Recall the passing reference in The Beatles’ song “Revolution,” released in 1968, or in Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film La Chinoise, the beginning of that much-lauded French filmmaker’s Maoist phase. In the United States, both the Black Panthers and the (overwhelmingly white) SDS hawked Mao’s “Little Red Book.”

We forget the obscene revolutionary posturing of comfortable Western leftists, an exotic species sadly still with us today. And we forget that Marxism-Leninism, Communist revolution, and ‘people’s republics’ led to mass murder, broken lives, unspeakable crimes, and unaddressed injustices on an industrial scale. For every Ceaușescu facing a firing squad, there were thousands of Communist apparatchiks who evaded punishment or any sort of accountability—some even comfortably rebranding themselves in political and economic life, whether in the post-communist East or in pleasant sinecures in the West.

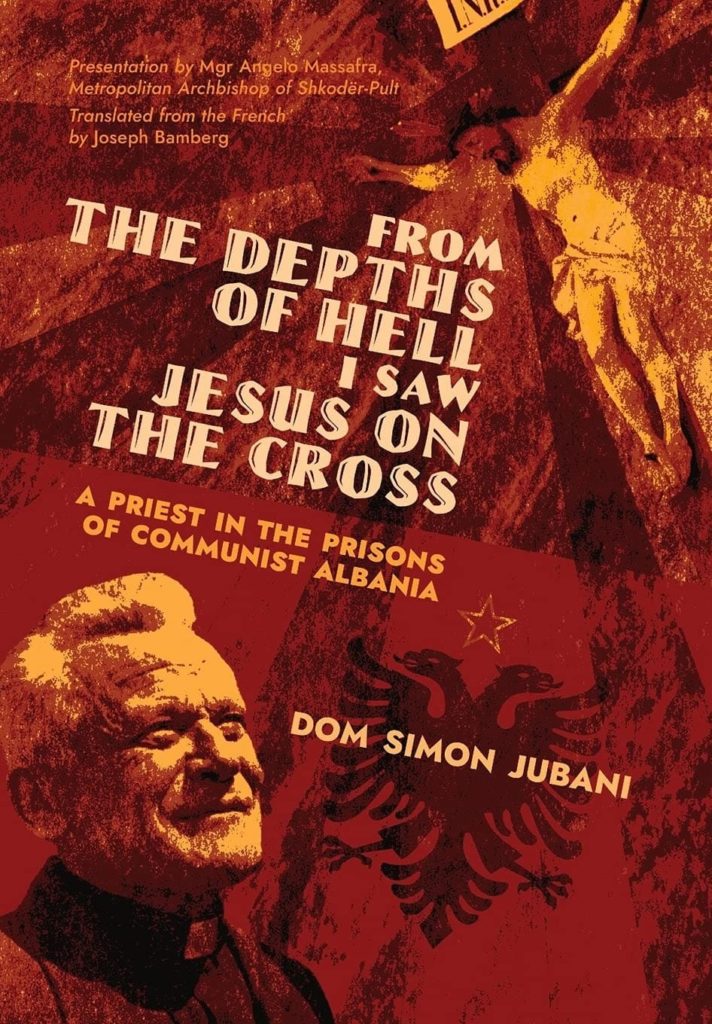

Pope Francis’s unusual act of making Albanian Catholic priest Ernest Simoni (b. 1928) a Cardinal in 2016 was an act of remembrance, honoring the martyred Albanian Catholic Church that suffered, along with all religions, under Enver Hoxha. Simoni spent 18 years in prison (1963-1981), most of them in forced labor. Still another act of remembrance is the recent publication of the prison autobiography of Dom Simon Jubani (1927-2011), a noted Albanian Catholic priest who spent 26 years in Communist prisons (1963-1989). Jubani would eventually, in November 1990, celebrate the first public Mass in Albania after decades of Communist rule and 23 years of State-imposed atheism. This book, first published in Albania in 2001 as Burget e mia (My Imprisonments), has appeared this year in French and English translations under the much more evocative title of From the Depths of Hell I Saw Jesus on the Cross.

Jubani’s book is a welcome addition to the record of Communist-era Christian prison testimonies which includes notable works by or about such heroic figures as the Protestants Richard Wurmbrand (Romania) and Watchman Nee (China), and the many works on the Soviet Gulag, including the classic account by Jesuit Father Walter Ciszek, With God in Russia.

It is almost as if Jubani was prepared to be a political prisoner. His collaborators and admirers describe him as “a nut with a hard shell,” “tough,” “passionate for the truth,” “uncompromising,” “provocative and justice-seeking,” and “highly intelligent though impatient.” He was an athletic priest (a former soccer star) who ministered to five mountainous rural parishes in the Mirdita region before he was arrested in 1963. The toughness comes across in print. This was not a mewling victim, but a man ready for death, combative—a bad inmate. He describes himself as “an active militant who went face to face with torturers and spies” at Burrel maximum security prison, one of the most notorious of over a hundred political prisons run by the Hoxha regime.

Although born in the nearby coastal town of Shkodër, Jubani seems as much a true son of Mirdita, the legendary, fiercely independent, tribal and Catholic part of Northern Albania—an Albanian Vendée. Mirdita, memorably depicted in Edith Durham’s classic 1908 narrative High Albania and its Customs, even briefly declared independence in 1921 against the newly formed Albanian state. A region which featured in Byzantine and Ottoman chronicles as wild and rebellious also resisted the Hoxha regime. After the Communists triumphed in 1945, the region fought on alone under its traditional tribal leaders until it was finally subdued in 1953.

This is a man of God who seems a warrior as much as a pastor. Even before his arrest, Jubani was indomitable. He interrupts the pro-government homily of another priest on Saint George’s Day, a sermon which mentioned neither Saint George nor God. “I got a reputation for being fanatically anti-communist. That was not such a great thing at the time, but I have to say that I ardently rejoiced.”

Jubani’s brother, also a priest, was poisoned by the Communists. It was, however, the perishing of his mother while he was in prison that marked the darkest day of his confinement. He witnessed unspeakable horrors, refused forced labor in the freezing dark of copper and pyrite mines, which led to beatings and isolation cells which—compared to being in a 4- by 8-meter cell with 30 other prisoners—was liberation. “The prison cell seemed to me like a monk’s cell. I was almost happy to be there.” He realized that in his work of serving the Church and saving souls as the Red Terror closed in outside, he had neglected his own soul. When he was released 26 years later, “a huge window had opened in front of me, from which I could see the whole world with my free eyes …. My eyes had been purified by physical tortures, which had immensely deepened my spiritual wealth.”

There are some difficulties in the narrative of this important work. Jubani starts at the end and goes back to beginning. The narrative is not as linear as one would like, with at times confusing digressions about Albanian history, politics, and ethnic differences which, while interesting and worthwhile, distract from the singular power of his life, imprisonment and survival under Communist Albanian rule. The English version is a translation of the French translation and so includes a couple of minor errors. The dreaded Albanian state security apparatus, the Sigurimi, is twice described in footnotes as the “information service” of the Albanian regime. It was of course the Secret Police, as mentioned elsewhere in the text. Jubani talks about past fighters against Communism and references Spain in the 1930s. He mentions an obscure “Huan Marces” who used his wealth as part of this struggle. Surely this is a garbled reference to Juan March, the Spanish magnate who helped finance Franco’s campaign.

Jubani also has no love for the government of the United States, which he sees as having done little to oppose the Communists. Then afterwards in the post-Soviet Union era, America, as Jubani sees it, embraced rebranded Communists while concurrently promoting the neo-liberal policies that played economic and political havoc in Eastern Europe during the post-Cold War era. In Albania, there no truth commission on the crimes of the Hoxha regime (Sigurimi secret police files were only opened in 2018 and the first public exhibition held in November 2021). Furthermore, the dictator’s old party, the Albanian Party of Labor, was permitted to reform itself as the Albanian Socialist Party and was accepted as a member in good standing of the Socialist International and European Socialists, all the while being directed by a leadership drawn from among the Hoxha regime’s top bureaucrats. Prosecutors in Albania have repeatedly refused to investigate the tens of thousands of disappearances under the Communist regime, dubbing them an “administrative matter.” The old priest seethed at the post-communist Albanian “democracy” of the ‘90s, a political farce and continuation of the old order, corrupt and venal. He would probably still be seething today.

You can still see some of the atheist propaganda videos produced by the Albanian regime. There was a special government media unit charged with producing these films. They are, predictably, rife with clumsy notions of human progress, with images of Darwin and the Inquisition. In one 1967 release, a Bektashi Muslim imam confesses to the tricks his community would play to deceive the people and bilk them of their money. Jubani notes that there were instances of public apostasy by Muslim clerics and Orthodox priests, but no Catholic priest apostatized. Told by his jailer that the regime has buried religion and that Communism is the future, he responded “you have not buried religion and you cannot. Christianity is an ancient religion, 2,000 years old. It has encountered every obstacle, every persecution, every polemic, every opposition, even those more violent than yours.” Many interrogators were completely unprepared for him, “they would stare at me wide-eyed, as if I had come from the moon.”

Jubani’s release in the waning years of the Hoxha regime, after the death of the tyrant, is both a triumph and a deception. “If the world had really changed, the most beautiful national monument (to the victims of the Communists) would have been erected there a long time ago.” And yet he was also able to re-establish parishes, rebuild churches and schools, and also baptize, teach and catechize, restoring what was lost. In his words, he appreciated the challenges of “a difficult apostolate, in places where atheism has sown the most evil seeds and where, as a result, wickedness, bitterness, ignorance and crime have grown.” This was a tough man for hard times, burned and hardened in the crucible. He lost all his teeth as a political prisoner, but he quipped, “I can eat a Communist every day.”

Particularly poignant is that first public Mass offered by Jubani, in November 1990, a Mass for the Dead in the month for remembering the Departed. It was held in a ruined and ransacked Catholic cemetery at Rrmajit, in the shadow of cynara thistles and cypress trees. It had been looted by people looking for valuables, vandalized by regime thugs, “half the crosses and photos had been torn to pieces with their names half worn off.” The faithful came to clean the graves of their loved ones, to right the crosses and put back the stones covering the tombs. And they came to worship. Remembrance is also the act of restoration, bringing back what was lost and is now found.