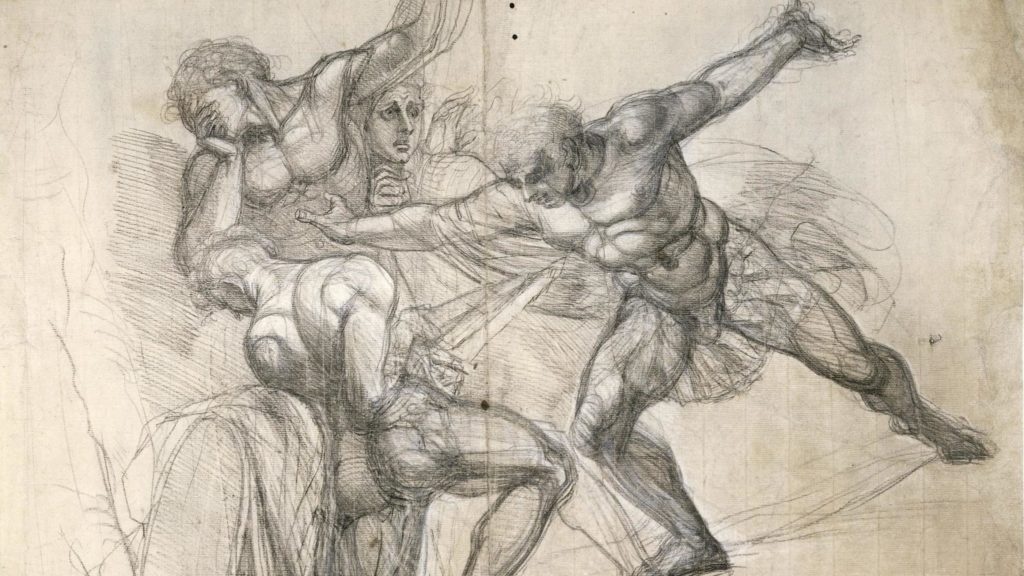

“The Death of Brutus,” a charcoal drawing with white chalk (ca. 1785) by Henry Fuseli (1741-1825).

Shakespeare’s four Roman plays feature no fewer than seven suicides. Of these, three are committed by senior characters in Julius Caesar: Portia, Cassius, and Brutus. The fact that Shakespeare’s suicides should be so predominant in these ancient history dramas is no coincidence, given how pagan Romans exhibited a puzzling admiration for the act of self-slaughter. This joins the growing list of historical realities about Rome of which Shakespeare seems to have been fully conscious. But the Roman glorification of suicide clashed entirely with the prevailing view in Shakespeare’s own time of what was then called ‘self-murder.’ Since St. Augustine, Christianity has regarded suicide as a grave mortal sin: ingratitude at the gift of life. For Romans, however, suicide could be understood as an expression of mastery: a noble unwillingness to endure slavery at the hands of external forces. Lucretia and Cato the Younger were the classic exemplars of this outlook, both killing themselves in rebellion against conditions which they deemed intolerable. For Portia, Cassius, and Brutus, suicide performs the same function, as the ultimate act of wilful renunciation once they find themselves cornered by fate.

In The City of God, St. Augustine argues that the injunction ‘Thou shalt not kill’ extends as much to self-murder as it does to the murder of others, writing “he who kills himself is a homicide.” Augustine raises the example of Judas, whose shame-induced suicide was less a noble reversal of his betrayal of Christ than a final denial of God’s grace. Is it not the case, Augustine asks rhetorically, that “by despairing of God’s mercy in his sorrow that wrought death, he [Judas] left to himself no place for a healing penitence?” Moreover, Augustine highlights the illogical cowardice of suicide, in light of the revealed truth of divine law. The committer of suicide, he says, inflicts “upon himself a sin of his own, that the sin of another may not be perpetrated upon him.” This fearfulness characterized the suicide of Cato, whose real motive, Augustine contends, was not a noble defence of republican principles; instead, it was “dictated by … weakness shrinking from hardships” and petty ambition to spite the victorious Caesar.

But despite what Augustine later argued, to pagan Romans these suicides made a certain amount of moral sense, as means by which both Lucretia and Cato could seize control over their ultimate legacies. For the raped Lucretia, the literary critic Gordon Braden explains, it was important “to secure her reputation for chastity among her family and social class,” while Cato’s suicide arose from a cunning desire to steal Caesar’s spotlight, “deny[ing] him the chance to look good by pardoning yet another former adversary.” Given the fame acquired by Lucretia and Cato, it is not surprising that Shakespeare’s Titinius in Julius Caesar should characterize the act of suicide as “a Roman’s part.” Lucretia and Cato, Shakespeare plainly recognized, were not emblems of disgrace in Roman culture, but models for emulation—at least in the right circumstances. Again, however, we see these principles come into conflict with later Christian doctrines. Augustine was perfectly aware of the high esteem in which Romans held heroic suicides, but he nevertheless saw it fit to draw a moral contrast between the mentality of the raped Lucretia and the outlooks of Christian women who fell victim to similar violations during the sack of Rome. Of Lucretia, Augustine writes: “this matron, with the Roman love of glory in her veins, was seized with a proud dread that, if she continued to live, it would be supposed she willingly did not resent the wrong that had been done her.” Augustine believed this sinful pride distinguished Lucretia from the more commendably Christian women who, themselves suffering greatly, “declined to avenge upon themselves the guilt of others, and so add crimes of their own to those crimes in which they had no share.” For in “the sight of God,” he concludes, “they are esteemed pure, and this contents them.”

The moral judgement issued by Augustine against suicide has had a profound impact on Western culture. We see its resonance not only during Shakespeare’s time, but even in the twentieth century writings of Christians like G.K. Chesterton, who denounced suicide in memorably lyrical terms: “The man who kills a man, kills a man. The man who kills himself, kills all men; as far as he is concerned he wipes out the world.” That the Christian West inherited this attitude is partly what makes Antony’s final tribute to Brutus as “the noblest Roman of them all” so confusing. The contrast between the Roman and Christian view of suicide is clarified in this strange moment, in which Antony appreciates from a position of deadly rivalry what Augustine condemns from a temporal distance. This is because Antony, unlike Augustine, shares a core value structure with Brutus: a commonly Roman outlook, anathema to Christianity, and best understood as a form of master morality.

But what is it specifically that enables Antony to pay tribute to what Christians like Augustine would later condemn? Even by Roman standards, suicide must surely be an expression of weakness, wholly distinct from the nobility exemplified by, say, Caesar’s conquest of Gaul? How could an act as final as self-destruction possibly be regarded as a triumph? The answer lies in Stoicism—the moral philosophy ostensibly followed by Shakespeare’s Brutus. Indeed, Stoicism can be understood as itself a variation on master morality, except that its chief end is less the assertion of mastery over others than the achievement of mastery over oneself. As the critic Wayne Rebhorn explains, “stoicism is a philosophy of will in which the wise man, like the warrior, becomes a hero, in this case by conquering the self.” Serious Stoics were thus inclined to retreat “inside the self,” loftily withdrawing from politics and the outside world. Brutus goes some distance to fulfilling the Stoic ideal with his final suicide, if it is understood in the terms described by Stephen Greenblatt: an expression of “heroic self-affirmation, the unwillingness… ‘to be made a wonder and a spectacle’ for his enemies.” Suicide for a Roman, then, does more than simply confer what Caska, one of the more junior conspirators, describes as “the power to cancel captivity.” Conceived in Stoical terms, it becomes a final flex of the heroic will, in which selfhood is asserted with glorious fatality. This is what enables even Mark Antony, the conspirators’ fiercest enemy, to admire the nobility of Brutus’s death by his own hand.

In Julius Caesar, Shakespeare displays great awareness of this Roman cultural oddity, which is confirmed when we examine his handling of the source material. The question is whether Shakespeare, being shaped by Christianity, re-distorts the picture created by Plutarch, or remains faithful to this heroic ethos like a scrupulous historian attempting to engage with another age. The astonishing thing is that, as well as absorbing a profound understanding of Roman culture from Sir Thomas North’s Plutarch, Shakespeare at times even overrules his source—not always for dramatic purposes, as we might expect, but also occasionally in the service of historical accuracy.

Translating a discussion about suicide between Brutus and Cassius, North makes Brutus sound discordantly Christian, hinting at some anachronistic notion of heaven: “I gave up my life for my country in the Ides of Marche, for the which I will live in another more glorious worlde.” The true sense of Brutus’s speech is therefore lost in North’s translation, which should really read as it does in most modern versions: “I gave up my life for my country on the Ides of March and have lived since then a second life for her sake, with liberty and honor.” It is remarkable that Shakespeare should have acted on his own instinct to repair North’s mistake by omitting any allusion to life after death. Indeed, Shakespeare’s Brutus, in the final conversation with his comrade, refers only to “everlasting farewell.” This is one standout instance where Shakespeare faithfully restores the Roman outlook (even at the expense of challenging the authority of his source), rather than allow the influence of Christianity to eclipse the pagan atmosphere being dramatically reanimated in Julius Caesar. Indeed, the absence of any afterlife in Julius Caesar is vital, as it emphasises the finality of suicide—the ultimate end of which for Shakespeare’s Romans can only be forging a legacy like Cato’s or asserting control over one’s destiny in the manner of Brutus.

In terms of dramatic portrayal, Shakespeare scholars draw a distinction between these heroic suicides which take place onstage and suicides of desperation, like Goneril’s in King Lear, which characteristically happen offstage. The first sort represents an aristocratic dignity, in which oblivion is preferred to physical comfort enjoyed in the shadow of one’s enemies. The second is an expression of pure despair and reflects a pathetic weakness. But how does Shakespeare assess the multiple suicides of Julius Caesar? Are they convincing as Stoic renunciations? Or are the philosophical justifications mere artifice, disguising the fact that Portia, Cassius, and Brutus despairingly meet their end as life’s losers?

It is notable that the main female character in Julius Caesar is also animated by the masterly values which might typically be associated with masculinity. Brutus’s wife Portia takes great and very literal pains to emulate Roman morality: “I have made strong proof of my constancy, / Giving myself a voluntary wound, / Here in the thigh.” This may seem sick-minded and pointless, but Brutus is filled with awe at Portia’s act of self-harm: “O ye gods, / Render me worthy of this noble wife!” As the feminist critic Coppeléia Kahn writes, Portia’s wound “anticipates the suicidal wounds of Brutus and Cassius,” which become “cultural markers of the physical courage, autonomy, constancy that count as manly virtue.” But Portia also anticipates her own, more savagely violent suicide with this voluntary flesh wound. Eschewing less painful means of self-slaughter, Portia kills herself by swallowing fire. Again, however, we encounter a discrepancy between Shakespeare and his source material. North’s Plutarch gives Portia a measure of agency in her suicide. Her swallowing of hot coals is described in vivid detail and the noble motivation is explained: “choosing to die, rather than to languish in paine.” In Plutarch, therefore, Portia’s suicide falls into the same category as Brutus’s: a memorably graphic refusal to endure dominion. Shakespeare, by contrast, does not stage Portia’s suicide. We learn about it through word of mouth, and her reasoning seems more neurotic: “impatient of my absence,” says Brutus; the product of “grief” and the way in which she “fell distract.” Kahn views Shakespeare’s rendering of Portia’s suicide as a parody of her earlier attempts to imitate the masculine Roman values: “a crazed, bizarre act of self-destruction”—one which “reinserts her firmly into the feminine” while the suicides of her supporting male characters retain a virtuous nobility. Portia’s self-murder, like Goneril’s, occurs away from the action and lacks the dramatic import of a centre-stage event.

But Kahn’s preoccupation with gendering the Roman values overlooks the way in which the male suicides in Julius Caesar, with the possible exception of Brutus, are hardly treated with unqualified admiration. If anything, the appearance of these suicides at centre-stage enhances their least flattering elements. Cassius, for example, certainly valorises the idea of heroic suicide, explaining the value of such an act even before the assassination of Caesar and the ensuing civil war: “Cassius from bondage will deliver Cassius; / Therein, ye gods, ye make the weak most strong.” Cassius here describes suicide as an admirable means by which a noble man can reject enslavement at the hands of his enemies. When, at Philippi, Cassius loses belief in his own power, his focus turns decisively away from success in life to constancy in death: “For I am fresh of spirit and resolved / To meet all perils very constantly.” His ambition of saving the Republic from Caesarism may seem hopeless, but at least he can retain a certain mastery by enacting a heroic suicide. Eventually, when the time comes, Cassius orders his servant to perform the long-anticipated act: “with this good sword / That ran through Caesar’s bowls, search this bosom.” Even in suicide, Cassius clings to a sense of his own mastery, boasting about murdering Caesar, as well as emphasising the inferior status of his attendant Pindarus, whom he took as prisoner in Parthia. But in the end, all of this is thrown into dark comic relief, as Cassius is robbed of his dramatically grand departure from life. Instead, he is made to appear foolish, killing himself before the battle is concluded because he believes, mistakenly, that his comrade Titinius is slain. The suicide by which he seeks to achieve glory is thus revealed not only as a clear expression of despair, but as a pitiable bungle, with very little honour in it.

Even before the outbreak of civil war, Brutus anticipates conditions in which he might be moved to end his own life: “I have the same / dagger for myself, when it shall please my country to need my death.” But Brutus is here attempting to illustrate the extreme measures he would take to preserve the Republic. And, of course, by Brutus’s own reckoning, the conspirators’ defeat at Philippi is not good for Rome. Rather, it marks the end of Brutus’s country as he knows it, such that his eventual suicide becomes more an act of solemn resignation than a worthy sacrifice for political ideals. Still he stays true to his Stoic philosophy, which he channels in his assertion that since our fates are unknown, it does no good worrying about them: “it sufficeth that the day will end, / And then the end is known.” And once the battle concludes in defeat for Brutus, his attention like Cassius’s shifts from restoring the Republic to safeguarding his legacy: “I shall have glory by this losing day / More than Octavius and Mark Antony / By this vile conquest shall attain unto.” The afterlife in which Brutus places trust exists not in some religious heaven, but in the “glory” of posterity which suicide can secure. Shakespeare takes the essence of this statement directly from Plutarch, in which Brutus says: “I thinke my selfe happier than they that haue ouercome, considering that I leave a perpetuall fame of our courage and manhoode, the which our enemies the conquerors shall neuer attaine unto.” In Shakespeare, as in Plutarch, Brutus anticipates being posthumously vindicated by the annals of history. But unlike, say, a Christian martyr, he is unable to find consolation in the knowledge that he has done right by divine law. His source of solace is the history books—which, being contingent phenomena, are really no less precarious and changeable than the Roman Republic he has just seen die before his eyes.

Nevertheless, Brutus retains some dignity in the act, which unlike Cassius he commits when every hope of material glory is lost and all that remains is the achievement of serene calm in the face of eternal oblivion: “Hold then my sword, and turn away thy face, / While I do run upon it.” But his composure should not be mistaken for weakness. Brutus’s Stoic suicide embodies a kind of master morality which, as the critic A.D. Nuttall explains, makes “every man a hero in his own proud psychomania.” Shakespeare’s recognition of the importance of suicide for Romans, particularly within this Stoical framework, demonstrates an ability to imbue his different characters with the respective spirits of their age. Indeed, the nominally Christian Hamlet agonises over the damnable implications of suicide in a way which Shakespeare’s Romans simply do not. This is yet another testament to Shakespeare’s powers as an historian of ethical values: his appreciation of the fact that moral convictions do not remain the same down the ages, but shift with the emergence of new creeds and the settlement of new orthodoxies.

But Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar does not self-evidently treat suicide with the same criticism levelled at Caesar’s egotism or the conspirators’ regicidal idealism. Portia and Cassius suffer very unflattering suicides, which seem to arise out of hysteria and short-sightedness respectively. But Brutus is another matter. Though there is something undeniably precarious in the way he entrusts his reputation to history, he does at least achieve a Stoical serenity in death which all Romans can recognise as noble. In this way, Shakespeare draws upon both Christian and Roman thought when examining self-murder. In Julius Caesar, he recognises suicide’s rootedness in despair, even as he portrays its heroic potential. The issue is dramatically raised, but no definitive answer is reached about the moral wisdom of taking a one-way trip to Hamlet’s undiscovered country.

Shakespeare’s opinions on matters of politics and religion have been widely regarded as notoriously elusive. In her recent bestseller, Emma Smith eloquently ascribes this quality to “the permissive gappiness” of his drama, which can sanction “multiple interpretations.” However, the critic is still equipped with instruments to shine light on these gaps. This is especially true of the Roman plays, which can be illuminated by examining the way Shakespeare used and even manipulated his ancient sources.

Julius Caesar engages with the nature of hubris, the pitfalls of revolutionary idealism and the moral wisdom of suicide in its various modes. Being a dramatic work, the play obviously cannot comment on these issues with the overt directness of a moral or political treatise. However, studied in tandem with North’s Plutarch, close attention to these central aspects of Julius Caesar can still be repaid by an enlarged understanding of Shakespeare’s instincts, if not his definitive opinions, as an historian and moral thinker. We learn that he was a perceptive historical observer, and we encounter strong indicators about his approach to and resolution of ethical questions.

According to the Romantic understanding, Shakespeare’s poetic genius consisted in his superhuman ability to transcend the controversy of ethical questions, contenting himself instead with the artistic beauty of inhabiting all perspectives while subscribing to none. Consequently, the impact of Christianity on Shakespeare’s moral outlook—even the sheer suggestion that the Bard adopted any outlook—has tended to be side-lined. This is not historically feasible and, when entertained, merely serves to alienate us from the true Shakespeare.

The Christian religion was essential to 16th century culture, such that excising it from Shakespeare criticism is rather like abolishing Marxism from the study of 20th century revolutions. Thus, we should acknowledge that Christianity will undoubtedly have shaped Shakespeare’s sense of right and wrong and examine the way in which this colours his impression of Rome. Still, while religion reached into every detail of Elizabethan life, Shakespeare should nevertheless be understood as possessing some measure of awareness over how he assimilated this Christian inheritance, just as we today can be the recipients of ideas without necessarily becoming their slaves.

The importance of religion is especially vital to analysing the Roman plays, given the considerable moral gulf between the Christian world in which Shakespeare existed and the pagan Rome he brings to life. Indeed, this disparity was noticed by near-contemporaries like Machiavelli and Rabelais; but we find its most systematic expression in Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals, where the dichotomy is explained in terms of slave and master morality. Shakespeare does display a certain measure of negative capability by using historical sources to inhabit this proto-Nietzschean mindset, imbuing his Romans with a realistic degree of masterly, aristocratic values. But pace the Romantics, Shakespeare also displays a readiness to challenge this world, rather than just sympathetically portraying its every aspect.

On the issue of Caesar’s character, we notice Shakespeare’s faithful portrayal of the Roman leader while nevertheless appreciating the way Caesar gets things so terribly wrong, by attempting to outgrow the human condition with which he should really make peace. The supposition that Shakespeare intended us to draw no conclusions from such tragic ironies appears to contradict everything that we know about human beings as judgement-forming creatures. The same applies to the mentality of Caesar’s conspirators who, in their regicidal confidence, leave Rome engulfed in flames that we are surely not expected to ignore.

However, in his discussion of suicide, Shakespeare comes closer to the negative capability which Keats especially admired, in that his view of the matter is left somewhat ambiguous. Portia and Cassius are two pitiable cases, in which an attitude of renunciation seems invoked as a mere cover for loss and despair. The Christian precepts of Shakespeare’s time are more clearly challenged in the sympathetic presentation of Brutus’s self-slaughter, from which authorial judgement is notably absent. In this moment, Shakespeare’s Brutus embodies the greatness of soul that was thought to be inherent in high Roman suicides, almost as if anticipating the powerful, if inconclusive, argument which Hamlet makes in favour of un-being.

But while the treatment of suicide remains ambiguous, much is made abundantly clear. Ultimately, what emerges from Julius Caesar is a strong sense of Shakespeare’s perceptive historical eye. He was as eager to capture the essence of Roman values as to bring his own Christian precepts to bear on the flaws of the main characters. Leaving aside the contentious debate about Shakespeare’s particular denomination, the cultural dominance of Christianity was such that he could hardly avoid measuring human action by its yardstick. Hence, Shakespeare’s appraisal of Caesar and his assassins powerfully subverts Nietzsche’s later paradigm, as we encounter characters enslaved by the very masterly passions which they mistake for a heightened form of liberty. Witnessing Caesar’s tragic fall from grace and the zero-sum bloodbath between the conspirators and the Second Triumvirate, we develop an enhanced appreciation for the importance of love and compassion in human relations. In a Roman world where both virtues were scarce, it is no wonder that suicide was so highly esteemed.