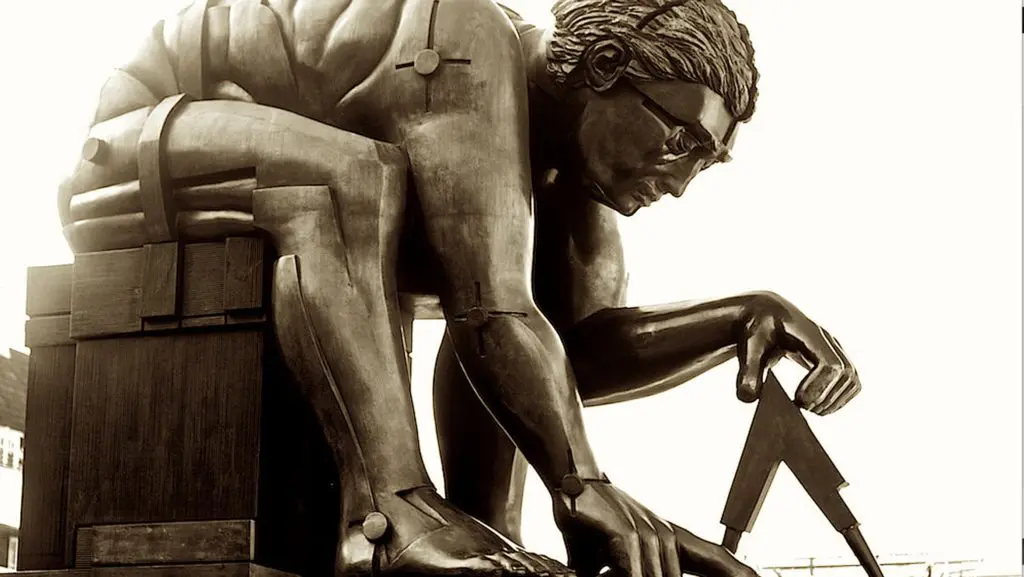

Eduardo Paolozzi’s sculpture of Isaac Newton in the plaza outside the British Library.

The far-Left campaign to repudiate Western civilisation shows little sign of slowing down. It was tempting to assume that cancelling giants as impressive as Nelson, Gladstone, and Churchill would satisfy whatever urge motivates this vengeful, destructive attitude to our history. But dining like termites on the remains of past heroes, it turns out, is an apparently moreish habit.

Last year, Sir Isaac Newton was added to the menu. As part of plans to “decolonise the curriculum,” Sheffield University rushed to clear itself of any association with the rather clumsily put-together list of allegations levelled against the scientific genius. Newton stood accused of “colonial-era activity” and encouraging a “Eurocentric” and “white saviour” approach to science and mathematics.

The documents did not give evidence in support of either charge, but it is easy to guess why Newton, born in 1642, is suddenly so irredeemable in this age of cultural vandalism. The “colonial-era activity” charge was probably based on Newton’s 1720 investment—from which he would later make a £20,000 loss—in the slave-trading South Sea Company. As for the charge of race-based Eurocentrism, Newton should have known better than to be born a white European during the scientific revolution and expect to get away with it.

But while the attack on Newton was no less lamentable than campaigns to cancel Gladstone and Churchill, there was something new. Suddenly, the woke wildfire was spreading not through humanities departments, which tend to succumb very easily to left-wing identity politics, but exhibiting signs that it was capable of melting the supposedly ‘hard’ sciences themselves.

Nor has this scientific aspect of the culture war showed any sign of slowing down since Newton’s posthumous cancellation. It emerged recently that new guidance to professors at Durham University had instructed the mathematics faculty to make the curriculum “more inclusive” and to consider the “cultural origins” of the concepts they teach. The guidance then adds that academics should second-guess their implicit prejudices if they are citing “mostly white or male” mathematicians, dead or alive, in their lectures and seminars. All this is part of a broader campaign to “decolonise” the department and make the syllabus more open, equitable, and inclusive to non-whites and women, as if intelligent minority students are so fragile they will be put off by Einstein’s whiteness or female brainboxes so unsure of themselves they risk being dissuaded by John von Neumman’s genitalia. Tellingly, the guidance asserts that there is a parallel between hard science and the humanities:

The question of whether we have allowed western mathematicians to dominate in our discipline is no less relevant than whether we have allowed western authors to dominate the field of literature.

The truth of a mathematical proof, rather like the less easily verifiable quality of a poem or novel, all of a sudden lacks primary importance if the proof’s historico-cultural roots stand accused of entrenching undue privilege, reinforcing ‘socially constructed’ inequalities, or otherwise being suspect. Thus, it is now possible for a maths teacher to smear the equation 2+2=4 for being “racist,” “supremacist,” and only “somewhat acceptable” in a mathematics curriculum. The question is no longer the one Bertrand Russell set himself in Principia Mathematica: “Is 2+2=4 unassailably true?” It has been replaced by another: “Does the widespread acceptance of 2+2=4 as unassailably true ingrain implicit bias and therefore perpetuate, say, racial injustice or Eurocentric supremacy?” And it is only superficially a question at all, for the answer is always “Yes.” According to the woke Left’s conception of social justice, there is no reason why ‘hard’ scientific institutions, including their ways of knowing and time-honoured methods, should not be subjected to a radical, deconstructive critique.

Canadian math teacher says "2+2=4" is "white supremacy." pic.twitter.com/jpebSsJ82G

— Christopher F. Rufo ⚔️ (@realchrisrufo) September 17, 2022

The intellectual origins of this guff are easy enough to trace. Before the emergence of postmodernism, classical Marxists and progressives of the New Left generally had invested their political hopes in the basics of Enlightenment philosophy. Science and reason, it was thought, would serve as our guardians in mankind’s ascent towards a just, more prosperous world. Eric Hobsbawm had nothing but praise for the project of Enlightenment and warned against the fashionable interpretation, informed by postmodernism and the rise of Critical Theory, of that period in world history as “a conspiracy of dead white men in periwigs to provide the intellectual foundation for Western imperialism.” The Enlightenment, went Hobsbawm’s retort, is the only secure basis, in the absence of any belief in God, “for all aspirations to build societies fit for all human beings to live in anywhere on this earth.” This long ago ceased to be the mainstream view in left-wing academia and among progressives broadly.

Indeed, the post-modern repudiation of metanarratives—universally valid truths about the world, nature, and society—required the ditching of both Christianity and Marxism, but so too it demanded a novel critique of the universalist pretensions of rationalism and the scientific method.

The Second World War was to blame for much of this cynicism. Intellectuals who led the “post-modern turn” in the aftermath of 1945 could not help noticing the manner in which science, far from being a neutral manufacturer of objective knowledge, had been weaponised by totalitarian regimes, whether fascist, Nazi, or classically Marxist. Why should science be spared critique for its role in creating, reinforcing, and perpetuating oppression, power, and privilege? This approach is not wholly wrong. Science is a manmade cultural activity. Accordingly, it is necessarily subject to constraints, from ideology and pride to every other species of human folly. Philosophically, however, the post-modern theorists failed to appreciate that science is not a moral realm. The scientific method yields insights about how the natural world is. But as David Hume taught us, science remains silent on how that world ought to be.

Skepticism of scientific institutions is surely warranted, even healthy. Cynical attacks on the scientific method as such, however, get us nowhere, for to accept the validity of an empirical method based upon what Karl Popper termed “conjecture and refutation” does not force us into any ethical conclusion, regardless of the results thrown up by any particular experiment. Even if we could prove by empirical investigation that red-haired Scotsmen have higher IQs than blond Germans, this data-point would not in and of itself justify the proposition that Caledonian Celts should enslave or liquidate any Teutonic Untermensch they can get their hands on. True, scientific knowledge can be weaponized by power, but the idea that science, as a reliable method for acquiring objective knowledge of the physical world, necessarily mandates any particular moral attitude to that world or one’s fellow men is fallacious and untrue.

Still, the postmodernists were ultimately obsessed with power, knowledge, and the relationships between them. And since they interpreted the world through a lens that detected power dynamics in every statement, method, or cultural activity, the ‘hard’ sciences could hardly claim immunity from this revolution of intellectual cynicism. The postmodern worldview, cultural critics James Lindsay and Helen Pluckrose argue, can be summarised in two basic principles. First, there is the “postmodern knowledge principle” which holds that objective knowledge and truth are unobtainable, since all ways of knowing, including the Western scientific way, are in essence socially and culturally constructed. (This is something of a philosophical non-starter, since the postmodernist, in making the assertion, implicitly concedes that at least some knowledge about the unattainability of knowledge has been attained.) Second, there is the “postmodern political principle” which revolves around the belief that knowledge is not randomly constructed by any given society or culture, but done so in a way that serves to reinforce existing hierarchies and to give an appearance of validity to what are, properly speaking, unjust structures of power and domination.

The first of these principles concerning knowledge finds its supreme expression in Michel Foucault. “In any given culture and at any given moment,” wrote the Frenchman, “there is always only one episteme that defines the conditions of possibility of all knowledge, whether expressed in a theory or silently invested in a practice.” Why, queries the scrupulous postmodernist, should a theoretical commitment to, say, scientific naturalism be any less prone to biases of time and place than any other culturally constructed theory or practice? (Of course, they will be at a loss to explain why the scientific method is thriving in places as culturally various as Boston and Beijing, but not enough to let it trouble them.) Moreover, on the Foucauldian analysis, those biases are not innocent mistakes, but inextricably tied to the sly enforcement of power and privilege. It is no wonder that the left-wing activists, dimly influenced by these theorists whom most of them have never read, are now coming for the science curriculum.

But why the obsession with race, gender, and sexuality? Is the political theory of woke progressivism, according to which Western societies are locked in a necessary zero-sum struggle between different racial, gender, and sexual groups, not just another complacent metanarrative? Why should neo-Marxism, if we wish to call it that, not also be repudiated, alongside its classical 19th century (bourgeoisie versus proletariat) variant, by the heirs to postmodernism?

The truth is that Foucault’s brand of activism leaves the post-modern intellectual with no positive purpose. There is religious zeal, but no ethical direction, no ultimately “good” true north. “If everything is dangerous,” says Foucault to his followers, “then we always have something to do. So, my position leads not to apathy but to a hyper- and pessimistic activism.” Perhaps so, but “hyper- and pessimistic activism” in the service of what? Pure wanton destruction? As I have argued elsewhere, Foucault has less to say about creating some new social order than on the need to expose and abolish the current one. This makes him less attractive to the present crop of budding revolutionaries than figures like Robin DiAngelo, Ibram X. Kendi, and others who peddle a more didactic creed of ‘equity,’ ‘diversity,’ and ‘inclusion.’

Lindsay and Pluckrose also make a case that the post-modern approach to society needs somewhere to go. The destructive impulse within man is strong, but we also possess unsheddable moral instincts. A political movement devoted purely to demolition, without meaningful, ethical ends in the name of which such demolition is justified, will not sustain itself for very long. In Cynical Theories, Lindsay and Pluckrose illustrate the shift from post-modern cynicism—which, of course, was completely incompatible with any kind of political activism—to the more loaded, didactic offshoots of Critical Theory peddled by progressives today:

New Theories arose, which primarily looked at race, gender, and sexuality, and were explicitly critical, goal-oriented and moralistic. They retained, however, the core postmodern ideas that knowledge is a construct of power, that the categories into which we organise people and phenomena were falsely contrived in the service of that power, that language is inherently dangerous and unreliable, that the knowledge claims and values of all cultures are equally valid and intelligible only on their own terms, and that collective experience trumps individuality and universality.

As a result, the negative push to “decolonise” the Western science curriculum is made reconcilable with the positive demand that it be replaced by something more socially just—justice here being understood, as per the ‘woke’ script, in terms of equity, diversity, and inclusion. Moreover, the post-modern suspicion of socially constructed, received ways of knowing makes it easier for the wokesters to advance their ideology without the burden of Socratic dialogue. After all, the very assumption that two interlocutors pursuing the truth wherever it may lead in a free and fair debate is the greatest route to knowledge, or that empirical evidence is key to making a persuasive argument about the state of society, is a product of systemic privilege and therefore illegitimate. As such, a white man requesting evidence from a black woman for her claim that structural racism exists is regarded not as a fair challenge, but as a sly invitation to participate in an epistemic game inherently rigged against black women and other victims. Unless the black woman can convincingly provide statistical evidence, of course, in which case logical reasoning and the methods of science appear, curiously, to be fine.

So, the pursuit of truth wherever it might lead has been replaced by whatever advances the higher truth of social justice. Of course, Plato also subordinated knowledge to goodness. In doing so, he departed from the teaching of the Socrates brought to life in the early Platonic dialogues that virtue and knowledge were one and the same thing: those who believe that knowledge is the ultimate good, says the entirely different Socrates of the Republic, “can’t tell us what knowledge they mean, but are compelled in the end to say that they mean knowledge of the good.”

The wokesters could make a similar case for putting their own idea of justice, a form of goodness, at odds with scientific rigour, which is a route to knowledge. But they would be wrong to do so. For Plato, knowledge and virtue are not enemies in a zero-sum contest, but mutually reinforcing values. He held to the view that virtue means more, and is in the final analysis more important, than knowledge. It is possible for an informed man to do evil, so it would be mistaken to argue that having knowledge is a sufficient condition for virtuous conduct, still less synonymous with it. But there was never any doubt in Plato’s mind that knowledge is a necessary condition for virtue. Modern progressives, meanwhile, routinely condemn the sciences and other forms of knowledge for supposedly conflicting with their understanding of virtue. Nothing could be further from Platonism, according to which all transcendent, ideal forms are held to exist in a realm of harmonious relation to one another. True, the form of Good is believed to rank higher than the form of Truth, but according to Plato’s understanding there is no actual conflict involved in aspiring to grasp both with one’s intellect.

Anyhow, even if it could be shown that science achieved preeminence in the world due to racism and imperial expansion, it commits the genetic fallacy to argue that the origins of a given method or proposition impinges on its truth. The assertion that “the Earth is round” cannot be debunked simply by pointing out that the person making this factual statement “learned the belief from his racist father.” Likewise, it is simple relativism to say that truth varies according to one’s zip code. The real melting point of phosphorus remains 44oC regardless of whether we conduct the experiment in the natural heat of Malawi or under controlled conditions in Massachusetts.

Still, the liberal Enlightenment idea that science is a self-justifying enterprise is exceedingly unconvincing. This is the view taken by Pluckrose and Lindsay, who appear to argue that scientific rationalism simply needs a greater number of courageous defenders to resist the ‘woke’ progressive siege: “Knowledge about objective reality produced by the scientific method,” they write, “enabled us to build modernity and permits us to continue doing so.”

Putting aside whether or not anyone should be seeking to claim credit for the modern world, the fact is that hard science, although it makes no necessary moral demands on those who practise it, at the very least “permits us” to do a lot more than “build modernity.” This is the strongest case to be made against the totalising claims made by scientists such as Richard Dawkins. The hard sciences are only as good as the culture which nests them. When you establish a totalitarian order which spits on the moral revolution brought about by Christianity and instead glorifies the will to racialized power above love and mercy, that culture will bring forth scientists like Josef Mengele. In the same way, when a culture as disenchanted as ours altogether loses the capacity for faith at all, be it religious or secular, and falls into a pit of relativism, that culture is likely to produce scientists all too willing to yield to the shrill demands of noisy, impassioned political activists.

If science is the only ground upon which our collective life rests, then life loses its moral meaning. And along with that loss goes an equal loss of the claim of science to be self-sufficient, for how can someone justify science by an appeal to science without making a circular argument? And if scientism provides no answer to moral relativism, but rather feeds that relativism by holding that science is the only game in town and yet cannot yield moral knowledge, then why should the science curriculum be spared by the new movement of progressive zealots? At least the wokesters regard themselves as true bearers of moral knowledge about what it means to be a ‘just’ society. If the scientific method presents an obstacle to this idealistic vision at any point, there is no doubt in the ‘woke’ mind about which one must give way to the other. In the name of their highly politicised understanding of goodness, the radical Left is quite happy to throw all sorts of knowledge—the reality of men and women, differential rates of crime between various communities, the humanity of unborn babies—onto the bonfire.

This is proof that the sciences cannot stand on their own two feet, as people like Richard Dawkins and Lawrence Krauss wish for them to do. Without the support of a confident, conservative culture which respects tradition and affirms that, while science is a near-miraculous activity, it cannot serve as the foundation for everything we value, the ‘hard’ sciences will crumble. In order to sustain themselves, subjects like physics, chemistry, and mathematics must be nurtured by a culture which holds truth, beauty, and goodness in high regard. But they must also exist within a society which appreciates that by letting the hard sciences dominate too much of the discourse, such that religious authority and the rest of philosophy are drowned out, it becomes exceedingly difficult for educated people to feel comfortable speaking in terms of truth, beauty, or goodness at all. For science at best has limited things to say about either of these values. It follows that our collective moral and aesthetic life will wither in a mechanistic world of pure science, leading to a desiccated relativism which dries out everything, including—eventually, at least—the integrity of scientific inquiry itself.

Our moral hunger will not rest satisfied with the scientistic assertion that such hunger is illegitimate. Far more likely it will take revenge on these spiritless scientists, who have contributed so much to our understanding of the natural world but have nothing to say about man’s soul, moral calling, or potentially heavenly destiny.

It is an awkward fact for a godless child of the Enlightenment to accept, but the evidence suggests that the aspiration of science to be a respectable, though by no means exclusive, province of knowledge in the Western world was probably more secure in the days of Christendom.